Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

In the 1960-70s, the emerging trends that were taking place in the realm of the visual arts became part of theatrical life as well, and resulted in the pioneers of environmental theater attempting to launch a war against traditional differentiated performing spaces (i.e. stage vs. auditorium). A desire to erase the limit between a real and illusory universes gave birth to a new movement, and attracted the attention of numerous theaters and studios - young and experimental companies that became actively involved in the process: Schechner’s Performing Garage, Grotowski’s Teatr Laboratorium, Malina’s Living Theatre, Stewart’s La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club, Chaikin’s Open Theatre, and Cino’s Caffe Cino amongst others. The merging of stage and audience hall proved to be an impossible task in the architectural setting of a traditional theater. Demand for a new space did not “allow” the existence of two zones separated by an arch. The notion of stage vs. auditorium gave way to the concept of a joint theatrical space. The plays were performed in unusual settings: hangars, factories, churches, cafes, on the streets…

The concept of environmental theater resonated with former soviet directors and artists as well (N. Beliak, V. Kharitonov). However, owing to the political system in power at that time, they have only manifested in fragmented experiments. In Georgia the only but most significant example of environmental theater was created in 1974 under the guidance of Sandro Mrevlishvili, and operated in the non-functioning Metekhi Church until 1988.

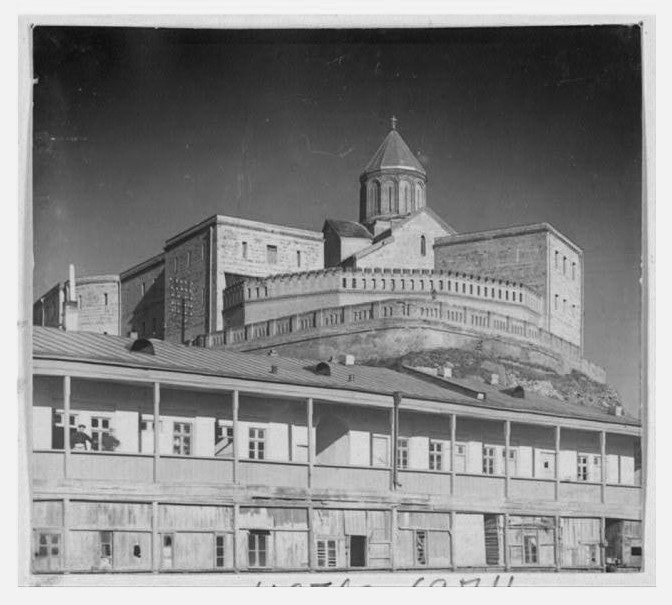

Metekhi Prison. 1910s. Photo by Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii. Library of Congress, USA.

It should be noted that in 1819, during the reign of Head Governor Yermolov, old Metekhi Castle was demolished and a new prison was constructed on the same site (Metekhi Church of St. Mary was located inside the prison yard). In 1933, following the decree of the Central Executive Committee of Georgia, management of the building was transferred to the educational commissariat. Art Gallery founder Dimitri Shevardnadze decided to transform the inner space of Metekhi Castle into a repository for museum pieces that would not fit into the existing storage spaces of the gallery.

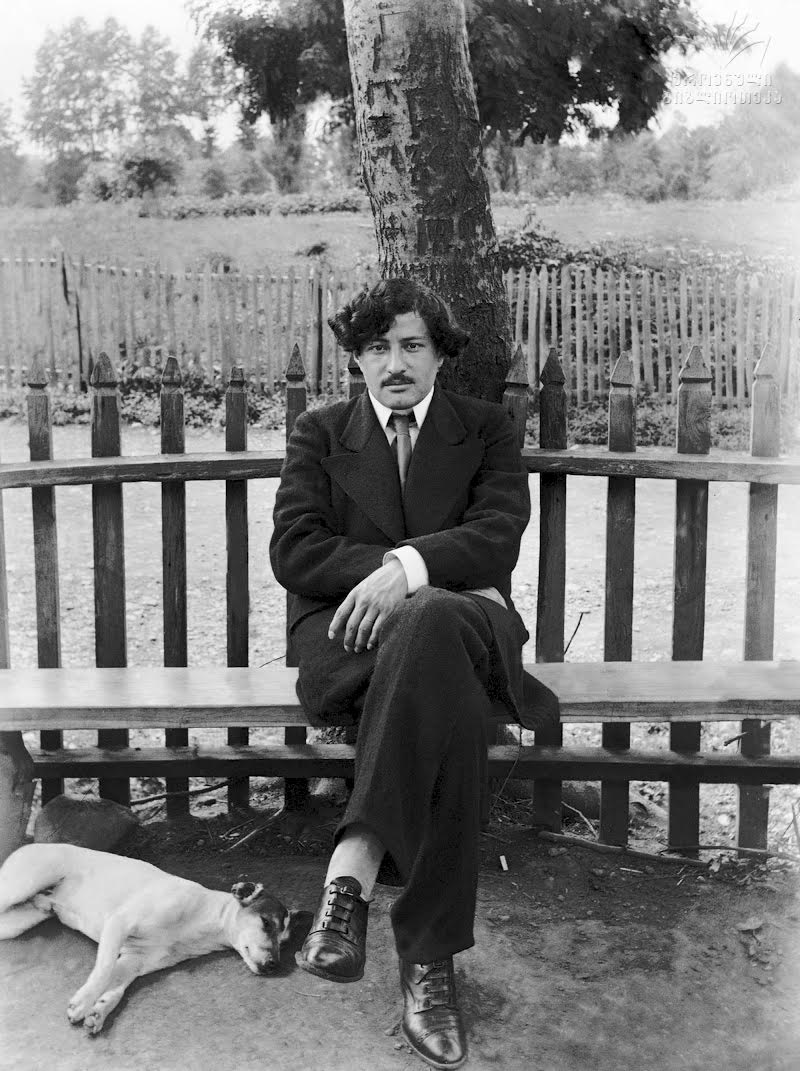

Dimitri Shevardnadze (1885-1937) Artist, theatre and film painter, founder of the National Gallery of Art.

The project aimed simultaneously to save Metekhi Castle from demolition and prevent Lavrenti Beria from executing his plan to celebrate Shota Rustaveli’s jubilee with the erection of a large monument. Shevardnadze stored some of the art pieces in a newly renovated section and began working on the project of the future museum. He fought off Beria’s team, who had been sent to the church with orders to demolish it, and together with Mikheil Javakhishvili, Sandro Akhmeteli and George Chubinashvili paid Beria a visit. Beria suggested creating a small-scale copy of the church to exhibit at the museum; however, Shevardnadze rejected the idea. As a result, the museum director was dismissed from his position, and the authorities launched a targeted defamatory campaign against him in the press. Soon afterwards, Shevardnadze was placed under arrest. The artifacts he had collected were first pronounced as having no museum value, and were later publicly burned in the yard of Metekhi Church. Dimitri Shevardnadze was declared an enemy of the people and executed in 1937, after having sacrificed his life to save Metekhi Church from being destroyed. The National Museum continued functioning at the castle until 1952. In 1958, the remaining two buildings of the prison were demolished, and the tip of the rock in front of the church was used to erect a monument of Vakhtang Gorgasali. In 1967 a festive inauguration of the monument was held, while the church remained closed for a prolonged period until religious ceremonies were restored in 1988.

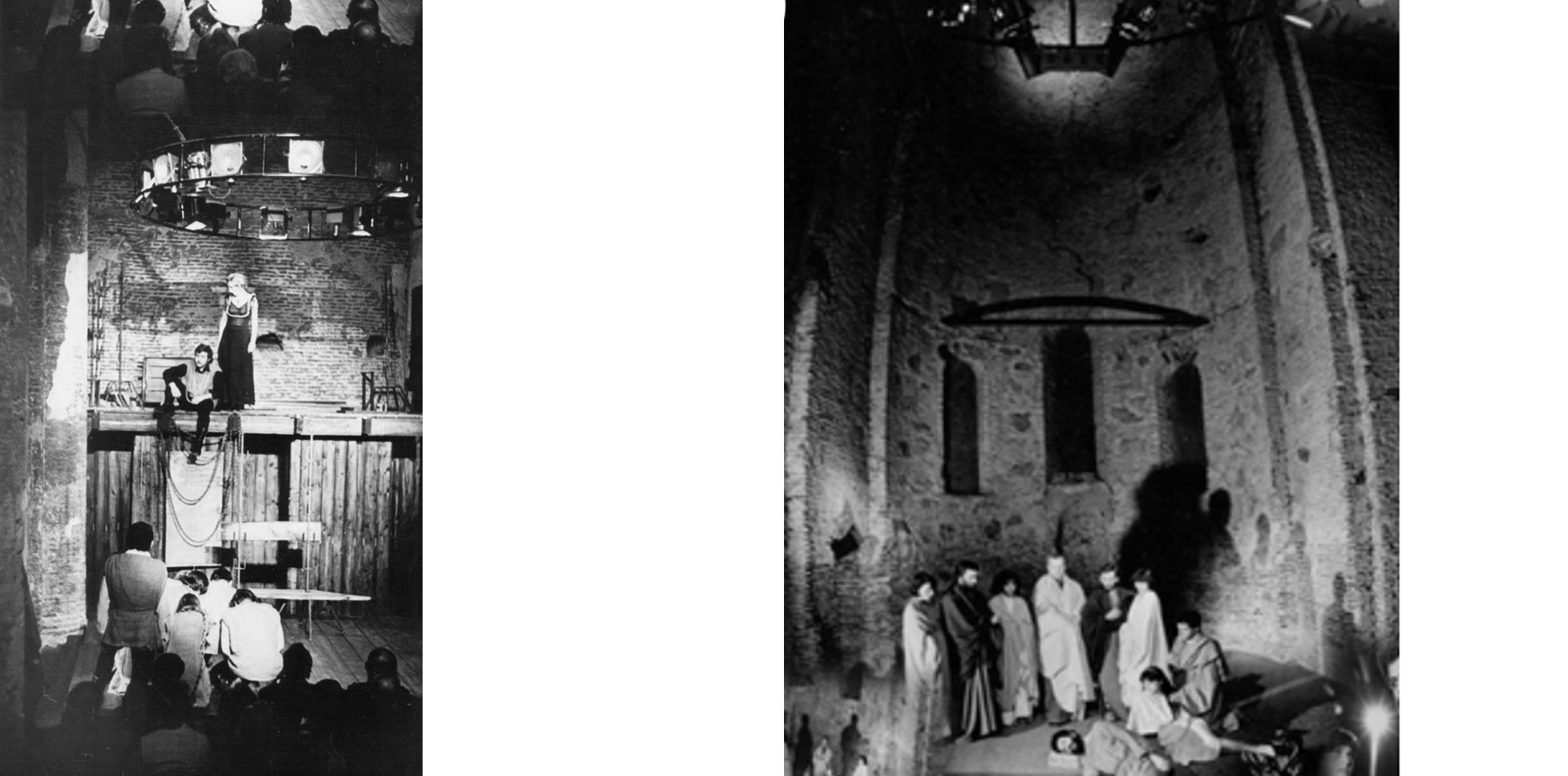

Hamlet. 1974. Metekhi Church. Youth Theatre and Studio Metekhi.

The Hermit. 1985. Metekhi Church. Youth Theatre and Studio Metekhi.

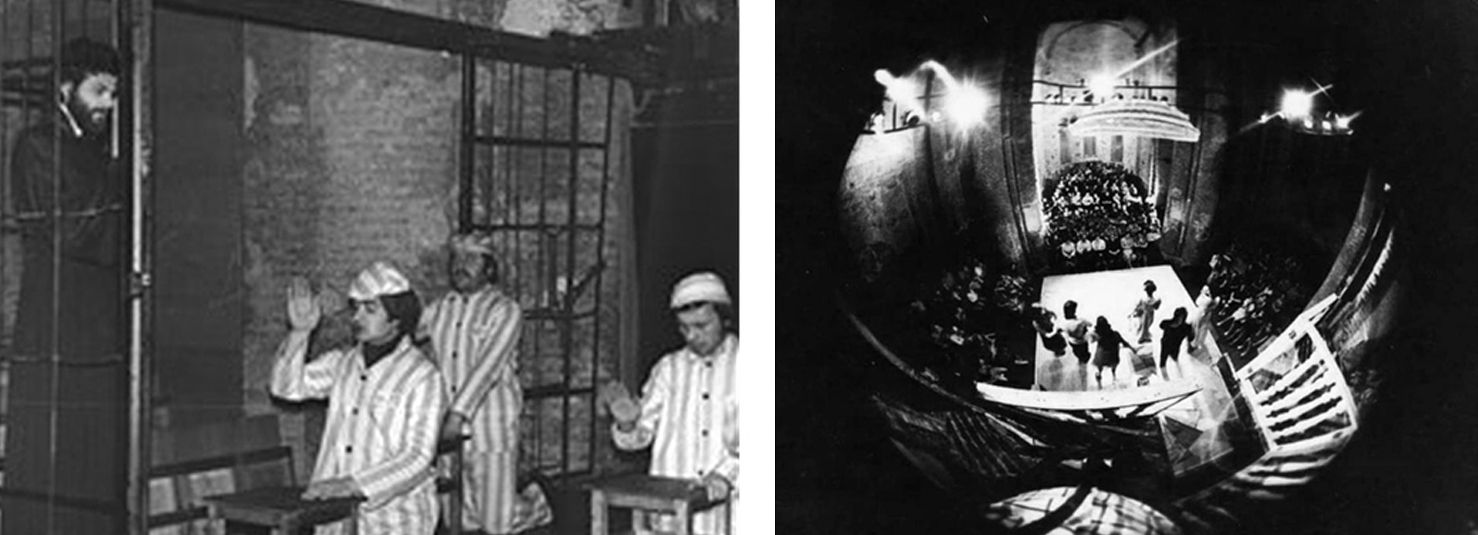

Lado Ketskhoveli. 1986. Metekhi Church. Youth Theatre and Studio Metekhi.

Metekhi Church. Youth Theatre and Studio Metekhi.

As already noted, beginning from 1974 the non-functioning Metekhi Church housed the State Youth Drama Theatre and Studio – the so-called Metekhi Theater, which was established under the leadership of Alexandre (Sandro) Mrevlishvili by graduates of the acting and directing faculties in the Shota Rustaveli Theater and Film University. As in other famous cases of environmental theatre from the US and Europe, the church interior served as a common neutral space (plays staged included: 42-74, Disaster, Chronicles of Boring Days, The Stove, etc.). On several occasions it offered the audience a specific atmosphere and environment (e.g. Hamlet, Macbeth). Even though use of the interior of the church as a “ready space” (sacred space) proved impossible, Metekhi Theater still managed to become the platform for a particular acting location. In this case its role referred to that of the prison that was functioning at this very site until 1933, rather than that of a church.

The play Lado Ketskhoveli suggested an interesting format of environmental theater and a ready-made space. The plot was based on documentary materials which informed the audience that “on September 23, 1902 Lado Ketskhoveli and his fellow 12 prisoners were transferred to this prison.”[1] The past was revived and made tangible before the attending audience. At the doors of the prison (the church entrance) they were greeted by the “prisoners”: “We become participants of a performance immediately upon entering the space. They welcome us in colorful prisoners’ garments and a torch in their hand, and usher us to our seats <. . . > The stage and the spectators’ hall are surrounded by prison bars. We are trying to find our way through them in dim light surrounded by the sound of rattling chains. Persons in striped clothes move to the stage. Who are these people? The prisoners who “reenact” Lado Ketskhoveli’s death in Metekhi Church.”[2] In some cases they played the roles of revolutionaries, and in others seminarians or gendarmes. The scene which encroached into the auditorium sometimes depicted a cell full of prisoners, a theological seminary council, the police chief's office, a shelter, and sometimes a well-known illegal printing house. “The border between the stage and the auditorium was practically gone. For example, the actors announced that in September 1901 the first issue of the illegal newspaper “Fight” was published. At that moment the audience members were already holding the historic copy in their hands,” [3] – recalls Kartozia.

In parallel with the establishment of the notion of "open artwork", which is so significant for postmodernism and is based on multiple interpretations, a special functional and ideological emphasis is allocated to the “reader” or recipient (in the case of theater – the viewer). If the work is a kind of configuration of stimuli, then the viewer becomes an active part of the combination of countless connections. In contrast to a self-sufficient closed stage, in an open space there is “nothing hidden away” from the viewers.

If

a traditional stage-box is intended for frontal perception and offers a common axis of attention for all attendees, an open space presents a special environment that does not strictly separate the two spaces (stage vs. audience hall) and acknowledges “multiple” points of viewing: the audience directs its gaze not only at the show, but at each other as well.

In the 1970s, a new form of theater was created in the unique space of Metekhi Church, where interconnection of the stage and auditorium determined a specific lively contact between the actors and the audience. The given theater was very far from performing the function of narrator-illustrator, and in a common diffuse space offered the new "role" of active participator to the passive spectator-observer. Metekhi Theater was an "open" space for communication and participation. This first Georgian example of "Environmental Theater" engendered a new, innovative format and context, which gave rise to the formation of one of the most relevant artistic languages of modern theater.

[1] M. Kartozia, Lado Ketskhoveli’s 110th Anniversary, We Were Peers, Literary Georgia, 1986, March 14, 12.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.