The Georgian National Museum is a scientific cultural institution unifying the country’s major museums, archeological sites, research centers, etc. It has inherited its institutional traditions from the first museum in Georgia, which was founded in the 19th century; at the same time the Georgian National Museum is actively involved in new processes in the cultural field, as we become part of a world-wide museum network.

Bolnisi Museum. Photo: Georgian National Museum / Fernando Javier Uqruijo

The study of history is a powerful tool and has been used for both positive and negative ends. Perhaps in Georgia’s case, a somewhat “heavy” scientific legacy was the classification of human races by Johann Frederic Blumenbach in the late 18th century. This German scientist coined the term “Caucasian race” based on the physical characteristics of a diplomat he knew – the first Ottoman Ambassador to England, who originally hailed from the Caucasus region. The “science of human races” was perpetuated by subsequent anatomists such as Professor William Lawrence, who again referred to the “Caucasian race” (1823, Lectures to the Royal College of Surgeons in London): “The name of this variety is derived from Mount Caucasus because in its neighborhood, and particularly towards the south, we meet with a very beautiful race of men, the Georgians.” Gradually, for the English-speaking scientific world, the European and “Caucasian races” became synonymous. Yet for Georgians and other peoples of the region, the identity of being Caucasian bore very different meanings.

D4500 – The 5th Dmanisi Skull discovered in 2005. Photo: Georgian National Museum / Guram Bumbiashvili

This is why we believe the stories of our past must be explored and examined, so that they can become tools for unification rather than division. Our main goal is to ensure that our rich heritage does not only remain in our archives, but helps move us towards new visions for a common future. Georgia’s European aspirations are not new. We have been a part of Europe, in the broadest sense, from prehistory to the present. Georgia is a multi-ethnic, multi-religious society whose history has been turbulent, but whose thoughts and culture have benefited from a diverse population and the traditions of many of its neighbors.

Otar Lordkipanidze Vani Archeological Museum. Photo: Georgian National Museum

Our Country is distinguished by magnificent landscapes, varied and unique endemic fauna and flora, and five climate zones that range from humid subtropical on the Black Sea to rural wetlands, high plateau and alpine regions, and even to the semi-desert areas of the southeast. Its rich natural resources have supported uninterrupted human habitation for thousands of years. Several archeological sites have been discovered on the territory of the Caucasus that are of universal importance for the history of mankind.

The Exhibition ‘Caucasus Biodiversity’ at Simon Janashia Museum of Georgia . Photo: Georgian National Museum / Fernando Javier Uqruijo

Archaeological research and the communication of many exceptional findings have brought our region into the spotlight of the world’s scientific community. This has given local scholars the possibility to work with international institutions and to become respected members of that community. I believe that both art and science are unique instruments for spreading values, and are strong tools for diplomacy. Using archaeological discoveries for nationalistic purposes, however, is nothing new and many countries claim to be “First”, “the Cradle,” or “a unique culture.” This sometimes manifests itself as a form of competition, rivalry to underline a country’s importance. A good example is the story of the “earliest Europeans.” Various countries have claimed this title after finding what they claim to be the “earliest” discoveries of hominids, our biological ancestors. In the early 20th century a lower jaw from Mauer, Germany, near Heidelberg, was considered to be the earliest known human in Europe, until in the 1970s a discovery from the French village of Tautevel became the earliest European at 450,000 years old. Even today, signs for tourists indicate that Tautevel is “the birthplace of the first European”. In the early 1990s discoveries from Ceprano, Italy and Atapuerca, Spain were dated back to 800,000 years ago, which in turn made them the new “First Europeans”.

Zezva and Mzia – the reconstruction of the earliest European human fossils dating back 1.8 million years discovered in Dmanisi

However, instead of creating competitions our task should be to create a win-win situation for all concerned. Even though in recent years Georgia has become known as the country of the “First Europeans'' it would be very naïve to consider 1.8 million-year-old creatures as “Europeans!” The Dmanisi discovery is indeed of immense importance for science, yet our approach has been to universalize the knowledge of human migration, rather than claim a distinction for being “the first.” However, the imagination of journalists was fired with new vigor for rivalry – the Dmanisi story has been featured worldwide through international media including cover stories in Science magazine, the National Geographic Magazine, The New York Times and many others; a quote from Liberation in 2000 following a congress in Tautevel read: “With these two fossils discovered in Dmanisi, Georgia, south of the Caucasus the first inhabitants of Europe became a million years older. This has been confirmed, which is not frequent in the realm of paleontology – no one contests the dates. Until now Spain and Italy vied for the honor of having sheltered the oldest humans of the continent, which dates back only 800,000 years.”

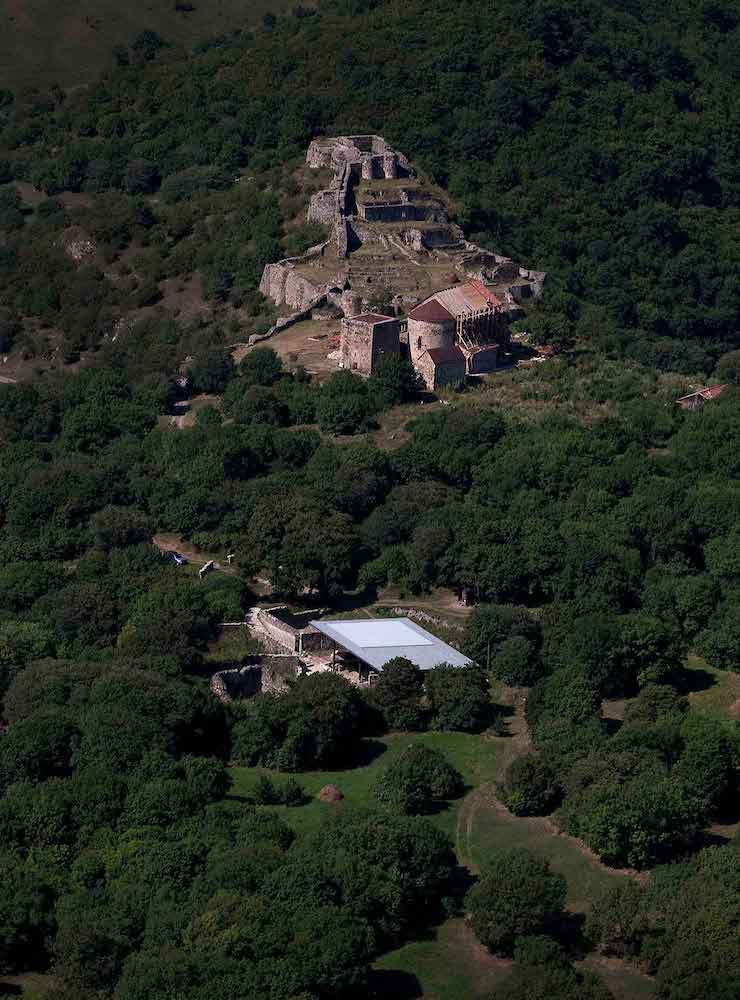

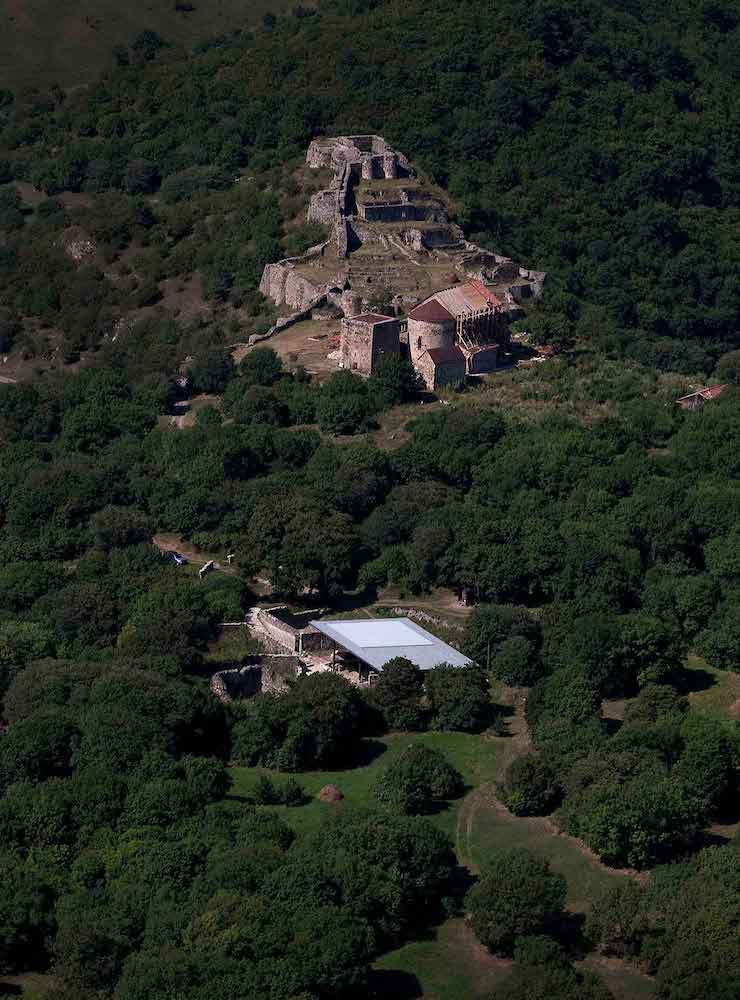

Dmanisi Museum-Reserve . Photo: Georgian National Museum / Fernando Javier Uqruijo

Dmanisi is a village about 85 kilometers south-west of Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital, and lies on the ancient Silk Road linking Europe and Asia. The site is rich in medieval and Bronze Age artifacts, but it is the wealth of prehistoric finds that has put it on the scientific map. Before the Dmanisi discoveries, the prevailing view was that when humans left Africa a million years ago, they had larger brains and sophisticated stone tools. But Dmanisi has changed these notions. The discovery of Dmanisi’s 1.8 million year-old human fossils has brought the Caucasus region into sharp focus as an entirely new region for studying the evolution of early Homo. Few paleoanthropological research projects have had such a powerful impact on our thinking about human evolution. These discoveries document the first expansions of humans out of Africa, and demonstrate that their migration was due neither to increased brain size, nor to improved technology.

Dmanisi Museum-Reserve. Photo: Georgian National Museum

Research of the Dmanisi finds began in the 1990s, and continues until this day, and still provides invaluable material for scientists participating in multidisciplinary research projects including archaeology, anthropology, genetic studies, etc.

The exhibition „Georgia - Cradle of Viniculture” at La Cite du Vin, Bordeaux, France . Photo: Georgian National Museum /Fernando Javier Urquijo

Another field of competition between countries has been “Which country is the “Cradle of Wine”?” again Georgia is in line for this distinction, since it claims to have the earliest traces of viniculture. The Caucasus occupies a territory within the Near East zone, one of the seven global “Centers of Origin” of food plants, where scientists believe the origins of agriculture and the domestication of important grains occurred. The varieties and forms of cultivated plants that originated in the wider Caucasus region have shown that the area was indeed an ancient center for the domestication and diversification of food plant species. In 2017 the world’s leading scientific institutions such as the University of Pennsylvania, University of Milan, Weizmann Institute in Israel and the Georgian National Museum finalized a long-term multidisciplinary research program confirming the oldest wine traces on ceramic vessels found at the Neolithic settlements of Shulaveris Gora and Gadachrili Gora, Georgia, dating back to around 6000 BC, which indeed proved Georgia to be the “cradle of wine.” The results of this study were published by the PNAS – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, and widely reported by the world’s media.

Qvevri – A Neolithic Jar. 6th-5th millennium BC. Khramis didi Gora, Kvemo Kartli. Photo: Georgian National Museum

Nevertheless, I would suggest moving from the competition of who is the “first winemaker” towards multidisciplinary research of the history of wine and other cultivated foods. The beginning of agriculture is a key period in human history, and offers another opportunity for researchers to develop high-level international inter- disciplinary collaboration. This could be the occasion to create another model like that created in Dmanisi, bringing together different academic institutions and working on public outreach. However, the story and materials from Dmanisi and Neolithic sites that attest to Georgia being the Country of the first Europeans as well as the Cradle of wine are represented in the newly opened branch of the Georgian National Museum – the Bolnisi Regional Museum, and of course at the S. Janashia museum of Georgia.

Exposition at Otar Lordkipanidze Vani Archeological Museum. Photo: Georgian National Museum

Most have heard the myth of the Greek Argonauts, but not everyone knows about the historic connection with Georgia through the myth of Jason and the Golden Fleece. According to the story told by ancient Greek authors, Jason and the Argonauts sailed to Colchis in search of the Golden Fleece that hung in a sacred grove of trees, and which was guarded by a dragon that never slept. Unearthed gold artifacts from Vani in western Georgia connect the history of this land to the myth of Jason and the Golden Fleece. Archaeological discoveries provide evidence of an advanced culture in what is today western Georgia, showing that the mythical land of Colchis was indeed located in this region. Many of these treasures confirm that Colchis was a real country, and that it was rich in gold.

Necklace. Detail. 5th century BC. Gold. Vani. Photo: Georgian National Museum / Fernando Javier Uqruijo

The touring exhibition of Colchis gold amazed the world with its uniqueness, quantity and beauty. One of the magazines on ancient Rome wrote that it was amazing to see the objects older than Rome itself. Today the culture of Colchis has found its place in the renovated Vani Museum-reserve and S. Janashia Museum of Georgia – both united under the Georgian National Museum umbrella. Georgia’s culture is also attested to be an indispensable part of Western civilization, since the kingdom of Colchis is one of the main pillars of Georgia’s cultural identity. Most scholars consider classical Greek culture as the basis of European culture and civilization. Greek or "Hellenic" culture has its roots in ancient Near Eastern civilizations, and it emerged after the campaign of Alexander the Great in the East. The archaeological discoveries show that pre-Christian cultural traditions in western Georgia contributed to the process of civilization. After the Greco-Roman period, Georgia was subjected to Arab invasions; however with the progress of the Byzantine Empire, the country forged strong links with European culture. Since Georgia became a Christian country in the 4th century, and also developed its own alphabet, the country was able to maintain its own identity. Byzantine cultural tradition began taking shape through a merger of this symbiotic culture with Eastern Christianity, embracing countries that included Georgia. Based on Hellenistic traditions, new cultural centers came into being in the bosom of Eastern Christianity, with their own national scripts and cultural traditions influenced by East-West civilizations. Here lies the uniqueness of Georgian material and spiritual culture, its attractiveness both to the East and to the West.

Monument of the Georgian alphabet. Stela, VI century, limestone. Davati, Kartli (East Georgia). Photo: Georgian National Museum / Fernando Javier Uqruijo

Due to its geographic location, Georgia has long been a natural crossroads for many powerful cultures. Nevertheless, the country has preserved its cultural identity, with an unwavering interest in the Western world. Now that the country is putting itself on the world map again, it is our genuine belief that European nations will be our partners on our westward path. Our goal is to develop common values while maintaining our unique cultural identity, to encourage diversity and tolerance while building bridges with other cultures.

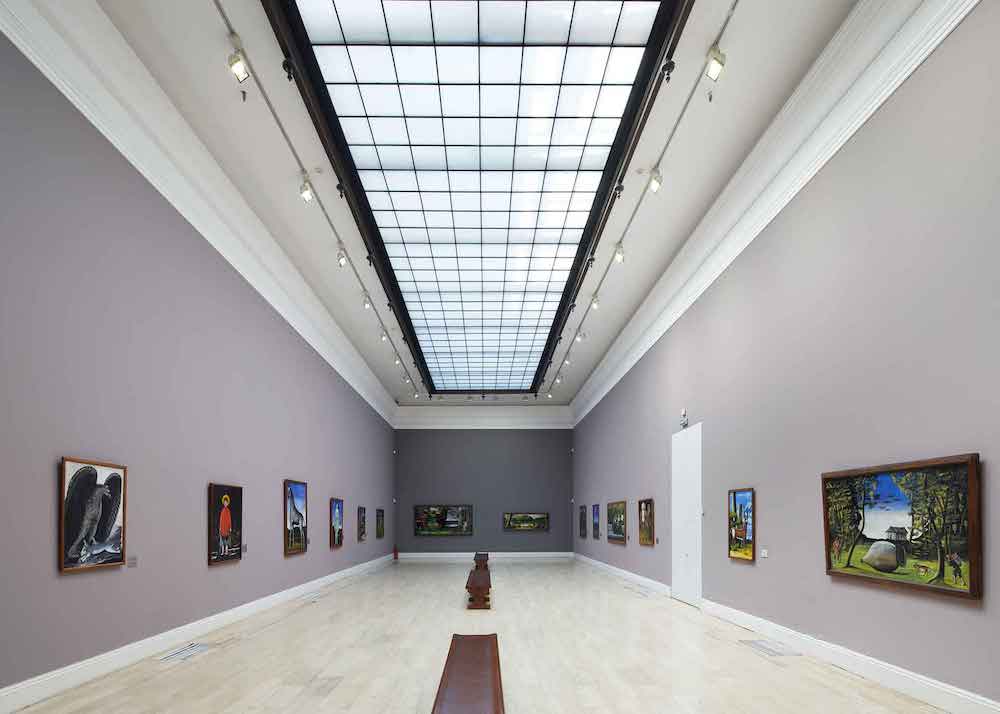

Shevardnadze National Gallery. Photo: The Georgian National Museum / Fernando Javier Urquijo

The Georgian National Museum presents internationally significant collections of art as well as dynamic, changing exhibitions that provide visitors with inspiration and knowledge of the wonderful world of culture, arts, sciences and education. Discoveries of the oldest human existence in Eurasia are displayed along with magnificent Medieval Christian art, stunning gold and silver jewelry from the ancient land of Colchis, spectacular modern and contemporary paintings by Georgian artists, and masterpieces that exemplify Oriental, Russian and Western European decorative arts.

Dimitri Shevardnadze National Gallery. Photo: The Georgian National Museum / Fernando Javier Urquijo

If there were a public opinion survey carried out on priority issues for Georgia, the main response would be “Education,” and if you ask Georgians what the country’s chief elements of national identity are, the answer will be its rich cultural history and Christian Orthodoxy. Indeed, I am sure that museums have a great potential for participating in educational and cultural processes and developing a balance between faith and knowledge. In order to develop wider European values among our young people, including those of diversity and tolerance, new exhibitions and public education activities are the best tools. The Georgian National Museum actively implements various programs to serve the purpose of public education, and I strongly believe that this institution should be part of the global cultural trend.