Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

.jpg)

.jpg)

Alexandre Koberidze’s film “What do we see when we look at the sky?” was among the top favorites in the press after its Berlinale premiere this year. The film received critical acclaim with particular praise for the director’s refined cinematic style and ability to capture everyday moments with spirituality and a poetic touch. Cinematographer Faraz Fesharaki’s work was also widely applauded. Not surprisingly, Koberidze’s work won the FIPRESCI (International Federation of Film Critics) award at the festival. This was the first time in almost 30 years that a Georgian film has participated in the main competition of the Berlin International Film Festival. The last time it was Temur Babluani’s “The Sun of the Sleepless”, which won the director a Silver Bear for his outstanding artistic contribution.

Making-of. Director - Alexandre Koberidze with cinematographer - Faraz Fesharaki. Kutaisi. 2019

For Koberidze - 36, this is his second feature film after “Let the summer never come again”, which also premiered at Berlinale in 2018. Shot on a mobile phone, the film won the German Film Critics Association Award and Gran Prix at FID Marseille. With an impressive, experimental debut and several captivating shorts, Koberidze had already established himself as a promising young filmmaker across Europe, but his new film’s success has raised his career to a completely different level. Koberidze has been living in Berlin for over 10 years. “What do we see when we look at the sky” is the director’s diploma work for the DFFB (German Film and Television Academy Berlin). He has been working on this project for the past 3 years. The film is German-Georgian co-production (DFFB, New Matter Films – Germany, and Sakdocfilm - Georgia). It was made with the financial support of the Georgian National Film Center.

Film Still. Actress- Ani Karseladze

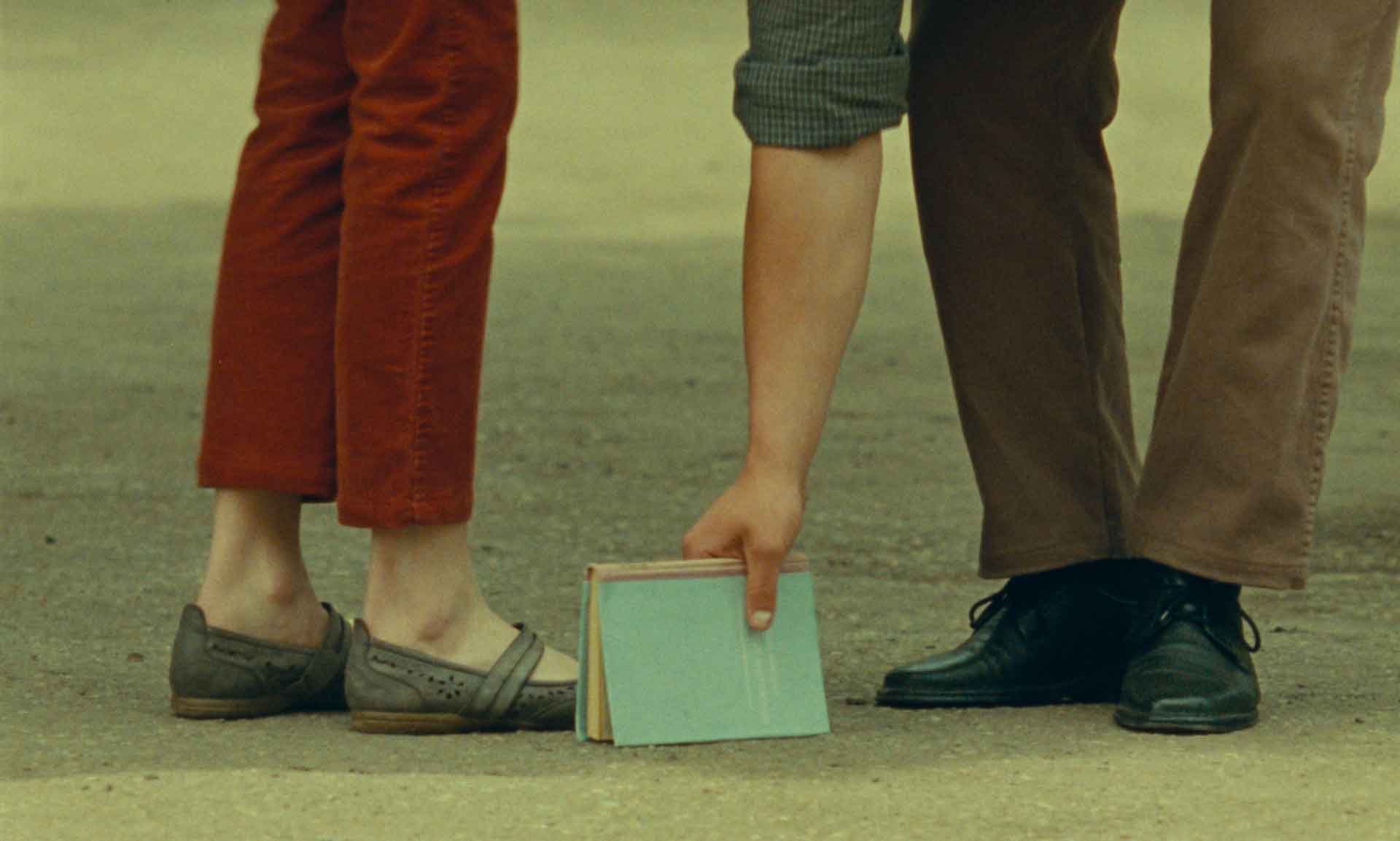

The film is set during the summer season in Kutaisi - an ancient Georgian town in the western part of the country. The plot focuses on a young man and woman, Giorgi (Giorgi Ambroladze /Giorgi Bochorishvili) and Lisa (Oliko Barbakadze/Ani Karseladze), who meet each other by chance and fall in love at first sight. They decide to meet the next day for a date without even asking each other’s names, but an evil spell is cast upon them, and on the morning of their meeting they both wake up with an altered appearance. The rest of the film follows their daily lives and how they navigate their new realities and new selves. Will they meet again? The film was already bought in many countries across Europe, as well as in the USA. It will also continue to travel around the festival circuit, but the details are not yet clear due to pandemic restrictions and uncertainty. ATINATI interviewed Alexandre Koberidze, who currently resides in Tbilisi, Georgia and plans to make new films here. He discussed his cinematic style, influences, and challenges in real and in fictional life.

Film Still

Berlinale 71 must have been very unusual for filmmakers and film crews – there were no red carpets, no premieres or reactions from the auditorium in the cinemas, just online screenings. What was it like to be part of that, especially when your film was the first Georgian competition entry for 30 years?

We knew from the very beginning that it would either be held online or would take place at another time. Before all the details were disclosed, I was thinking that if it would only be held in digital format, maybe we would not participate, because I could not imagine what it would look like. When you have to watch several films a day during the festival, I thought that the chances of seeing it the same way and with the same amount of attention were very low if computers were used. Then when the film was selected for the main competition, which was a huge surprise for us, it was hard to say no to such an important event. Besides, it was declared that in June there would be special screenings of Berlinale films, where the general public will have the opportunity to see the films in movie theaters.

How did the festival take place? Reactions, opinions etc. The film received very positive reviews from most of the press, which is quite rare even for famous filmmakers. As such, the FIPRESCI award was not a surprise to us, but many in Georgia thought that it would also win one of the main prizes as well.

On the first day I was quite nervous - you don’t know how people will react after the premiere. Will they like it or not, or it will go completely unnoticed. When I woke up the next morning, the interest was obviously huge. I received a lot of massages, read many positive reviews and what was most exciting for me was that the authors were focusing on such details, that I knew they had watched the filmed till the end. Regarding the prize, we were not thinking about it to begin with: it was already a great accomplishment for the film to be selected for the main competition. Then, after all these reviews and messages, when everyone was writing: “you should win,” “congrats in advance,” etc, it kind of created some expectations, but I knew that we would not win a Silver or Golden Bear. However FIPRESCI was a big thing as well. Overall, what happened was more than enough for now.

While watching some episodes from the film, you can feel some visual resemblance to and the spirit of old Georgian classic cinema and the aesthetics of classic movies in general. This has also been mentioned in several reviews. Your deep knowledge and love of cinema is obvious in your other works, too. However, in recent decades new generations of filmmakers have mostly lost contact with the traditions of Georgian cinema. What is your relationship to it and what inspired you to make this movie?

To work properly, it’s important to be able to communicate with the past, with traditions - this is common to every field. While working you can reject this past or be in love with it, but the result is usually achieved in relation to your predecessor. Since the birth of cinema, despite the gap we had in the 90s, movie production in Georgia has been quite intense and competitive, reaching notable success from time to time. Then suddenly everything stopped. Some works were occasionally created, but the connection with the past was broken and the traditions were partly lost. This gap had to be restored. Fortunately, we will soon be able to see a finished version of the film „ Shvidkatsa” by the late director Soso Chkhaidze, who filmed it in the 80s and partly edited it, but since his death in 1992 the film has been waiting to be completed. I think this film can play a crucial role in restoring those lost connections. I was lucky to have seen some parts of it, and now I see how much it influenced my film. I also watched his “Tushetian Shepherd” several times before filming. While working I’m usually very careful about choosing what to watch, since it’s easy to be influenced at that time. Accordingly I try to watch films that will inspire me in a positive way. We also watched “An Unusual Exhibition” - this wonderful movie was shot in Kutaisi as well, “Feola”, “Falling Leaves”, “The Way Home” - what could be better influences?

In all of your films the story is mostly told by the narrator; the actors’ voices can rarely be heard. Although there are some dialogues in this new movie, you maintain the same tradition here as well. Where does this style come from and why do you like it?

It goes back to my childhood experience. I started reading books by myself quite late, as my grandmother used to read everything for me. I grew up listening to narrated tales. I think it’s deep-rooted in me, because most of the stories I perceived were narrated, and somehow I feel like this is a better way for others too. Moreover, sometimes it’s a bit uncomfortable for me when actors and actresses have their own voices and speak too much in films, especially in my own work. In my childhood we used to watch films on TV, where only one voice would do a voiceover of the actors and their original voices were only heard somewhere in the background. I still love this effect, and I see it as one of the ways of alienation.

Cinematographer-Faraz Fesharaki. Kutaisi. 2019

Your previous film “Let the summer never come again” actively explores city life. We could say that Tbilisi is one of the main characters there. In this new film you are capturing the sense of Kutaisi. Cities in your films are not portrayed as superficial and glamorous-touristic, but rather seen from inside, with their problems and beauties. This is interesting because contemporary Georgian cinema lacks urban reflections. How important for you is the dynamic relationship between city life and the environment we live in?

This began in my previous film. I spent a very long time wandering around the streets of Tbilisi, searching for locations. I’ve always been very sensitive regarding what’s happening in this city. While working, I understood that on one hand I wanted to reflect things that would be disappearing soon and that have already disappeared, while on the other hand I also wanted to shoot the city the way I see it. I love this city very much, and it constantly surprises me how attractive it still remains after all the bad things we’ve done to it. I didn’t plan to follow the same path in the new film. On the contrary, I was planning to shoot only certain locations and not go that wide. But after I spent almost a year in Kutaisi, this city enchanted me so much that every time we went somewhere, I was like “maybe we should also do a scene here, maybe something should happen here too”. Every time we walked around, a new scene was added to the script or some scenes would move to a new place. So the city changed the script spontaneously and became an integral part of the film.

How did Kutaisi become a filming location - was it planned beforehand? It’s been a while since we’ve seen this city in Georgian films. Is modern Kutaisi a cinematic place?

Yes it was planned; I knew that I didn’t want to film in Tbilisi again. Then I wrote another script for Batumi, and Kutaisi was the only big city remaining. Besides, I encountered some strange coincidences. For example in the first version of the script one of the leading characters works on a boxing punch machine. When I arrived in Kutaisi, the first thing I saw was this machine standing right next to the White Bridge, just as in the script. Later this scene was removed but these coincidences and symbols attract me very much. Today I understand that if we had made film in another place, it would be much different and probably worse than it is now. The sense of hopelessness, which is common for modern humans and was also a part of our film, was changed to joy and hope in Kutaisi. People we met there and the places we saw, turned into a source of hope for us. I’m not romanticizing anything: the difficulties and problems which exist there, are very clear to me, but there is something that is happening there right now and it should not be accidental that precisely this place is the center of the events, that gives hope to the whole country - The Rioni Valley is in the heart of the country and a source of hope today, and each of us is responsible for its protection.

Film Still. Actor- Giorgi Bochorishvili

Most of your films have some elements of magical realism and mysticism. In this latest one the whole story is based on the magical transformation of the leading characters. What attracts you to fairy tales and symbolism?

Unexplained things are always charming, but somehow these elements are eliminated from everyday life, while I think they belong right here. In most contemporary films where such events take place, they are used as metaphor; or maybe strange things happen, but in other universes and not ours. I wanted the things happening in my film to be seen as fact and not as symbol or metaphor; something that occurs here and now, and not in a parallel universe.

Football has a significant role in the film. There’s a world cup taking place and everyone is watching it and involved in it. I can see here another reference to old Georgian movies. What inspired you to introduce this sport into the film on such a level - are you a football fan as well?

I really love all those old movies about football: “Feola,” “The first Swallow,” “Ball and Field.” And yes, I love football very much, and when we talk about magic and miracles, one of the real magical events where we see unexplained miracles is football. There are players who do unbelievable things that are truly inspiring. The same is true of cinema; but in football everything is very clear and simple - you watch everything in real time, nothing is hidden, no editing. In film, people work behind the scenes and you see the result later. There is hard work behind every game for sure, but all those magic things happen right before your eyes and cannot be repeated even by an author. A year before we started working on this film, we went to Kutaisi to shoot. It was the summer of 2018, when the World Cup was in full swing and we wanted to film how people in the city were watching football. We shot many scenes at that time, many of which were used later in the film.

Mixing documentary and fiction is yet another trait of your films. How do you manage to tread this path in the proper way and sense the audience’s feelings and expectations?

Observing ordinary things and real life situations is really fascinating for me. I also like to create similar environments while filming, but want there to be other layers as well. When you want to reflect something around you, a time or a situation, the big question is how? Which style would be more appropriate? You may turn on the camera and take some documentary shots, but can’t capture the atmosphere adequately, while sometimes artificial settings might help to understand and feel the event better. I like both: I like to film raw reality because there are some things that cannot be planned, and there is a rhythm, which cannot be orchestrated artificially. On the other hand, it’s a challenge to create these realities and rhythms by oneself. For now I’m trying to do both.

How was the casting process held? I’ve heard that most of the actors were non-professionals.

I try to work with both. The practice is different, and this difference is interesting. Some of them I meet in the streets, some I might see in another film, some are my friends, etc. In this film, out of four major characters only one, Giorgi Bochorishvili, is an actor. But for one of the roles we cast Vakhtang Fanchulidze, who was once a movie star. It was a very special experience for me to be able to work with him. We needed a lot of people, so I scrutinized everyone around me. We had auditions too, but some of the actors I met by chance. Most of the cast is from Kutaisi. I love that period when you are looking for actors. You are working all the time, even when you are in a bar enjoying your free time.

Making-of. Kutaisi. 2019.

You are an actor as well; you have starred in several German films, the most recent of which also premiered at Berlinale this year. What kind of experience is this for a director? Does it help while working with actors in your films?

Standing in front of the camera is not my natural situation, I feel much better behind the camera. I’ve only played in my friends’ films, where trust is important. Being an actor is a complex and difficult profession, one of the issues is that you never know what you have participated in until the film is finished. The script, director and filming process might be fine, but in the end you may discover that you are part of something not very good. When an actor agrees on a role, it means he/she trusts the authors. It partly depends on experience and intuition, but generally the film is in someone else’s hands, and this is quite a tricky position. That’s why I only act for friends, for people I trust.

Are you working on something new? What are your plans for the near future?