Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

The artistic cafes of Tbilisi are a significant component of Modernism, a period from the end of the 19th century until the 1920-1930s when similar cabarets, clubs and cafes conquered almost all the major cities of Europe, including Moscow and St. Petersburg.

They became an important element of the creative avant-garde of Tbilisi in 1917-1921, and shaped a cultural context that advanced the Modernist way of thinking and fostered experimental artistic forms: an immersive space, which brought together different types of artists and art forms, introduced a special way of living among the artistic community, and was defined by John Bowlt as “café culture”. The environment of the Tbilisi avant-garde, with its multilingual and multiethnic, multistylistic, noisy, avant-garde rhetoric and provocations through an unusually tolerant way of acting was mainly manifested in the spaces that were sacralized with the works of Ilya and Kirill Zdanevich, Iakob Nikoladze, Aleksandr Petrakovski, Sergei Sudeikin, Aleksandr Bazhbeuk-Melikov, Lado Gudiashvili and David K’ak’abadze.

The history of Tbilisi’s artistic cafes, which extended over 5-6 years, began in 1917 with the establishment of the Fantastic Tavern. In 1918 the Peacock’s Tail and Argonauts' Boat were added, and in 1919 - Kimerioni.

According to Titsian Tabidze, the members of the Blue Horns group were given the cellar of the Artistic Society (today the lower foyer of the Rustaveli Theatre) for the establishment of a “grandiose café” there.

Building of the Artistic Society

They named it Kimerioni and to decorate it they invited Sergei Sudeikin – artist of the Russian Imperial Theatre and decorator of St. Petersburg’s artistic clubs Stray Dog and Shelter of Comedians. Sudeikin, who happened to be in Tbilisi at that time, was joined in his work by Lado Gudiashvili and David K’ak’abadze.

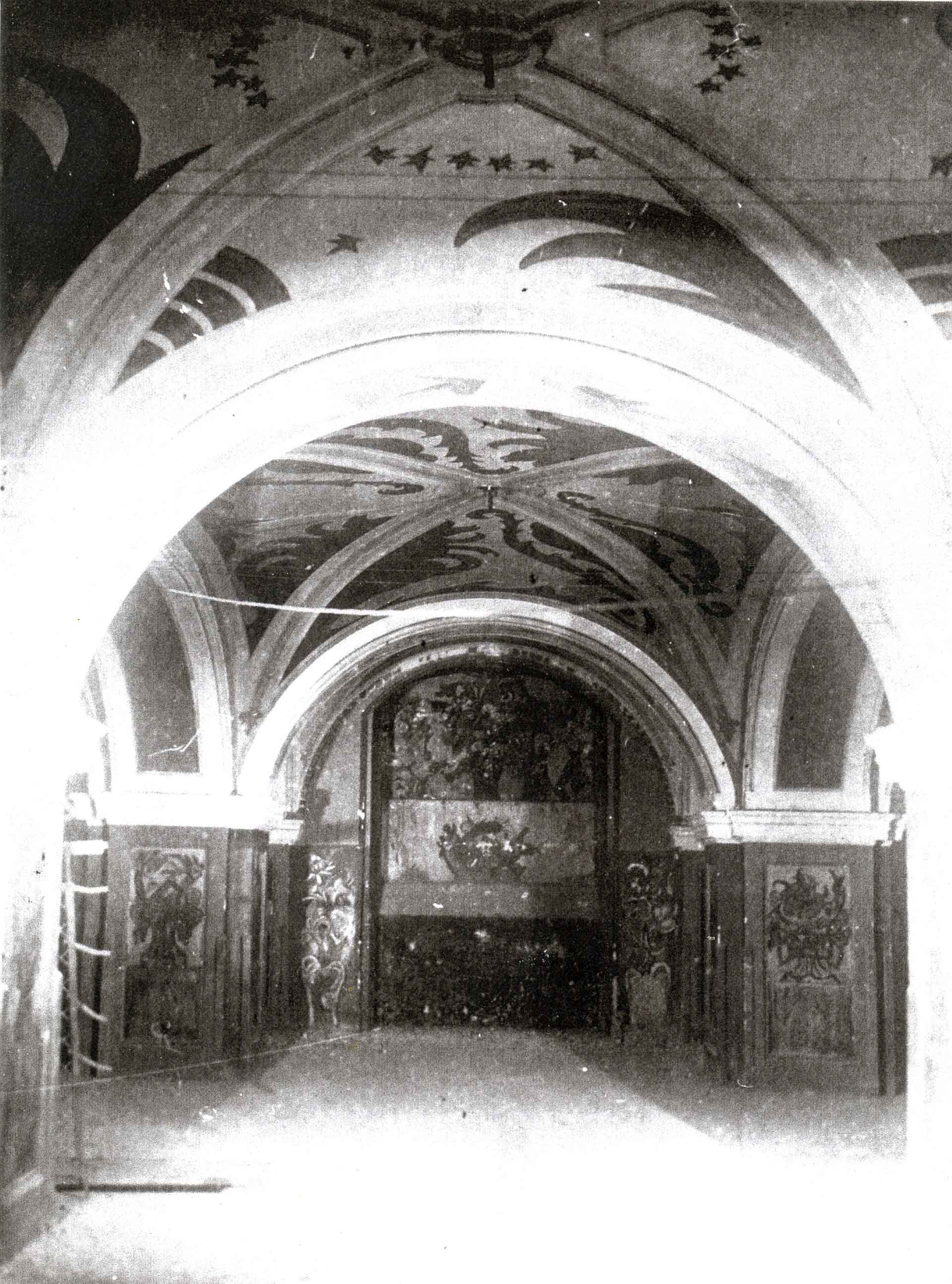

Kimerioni, interior (photo of the period)

Kimerioni, interior

Kimerioni closed its doors in 1922. Afterwards its walls were painted over, and the café was transformed into the foyer of the Rustaveli Theatre. When the first layers of paint was removed during restoration works, the workers discovered that most of the paintings were still intact. However, the sections produced by Sudeikin (the Georgian Poets, a Broken Mirror, On the balcony, the Dancing women) that were seen in old photographs and described in the recollections of his contemporaries, as well as Gudiashvili’s Warden Fox, were lost.

.jpg)

A Broken Mirror, Kimerioni, Sergei Sudeikin (photo of the period)

.jpg)

Stepko’s Tavern, Kimerioni, Lado Gudiashvili

To reach the main hall of Kimerioni, the guests first needed to descend a long staircase. At the top of the stairs to the right of the entrance they were “greeted” by Lado Gudiashvili’s Stepko’s Tavern – a monumental work with its generalized composition and structured static space. It represented the very characteristic environment of Tbilisi’s taverns, including boxes full of fruits and vegetables, wine bottles on the shelves, and wreaths of produce that were hung on the walls. Stepko, who was standing at the middle of the counter with his hands on his hips, displayed a proud posture and the gaze of a Tbilisi inn keeper.

With an artistic gesture he invited the guests into the tavern. Gudiashvili welcomed the audience of the café with a traditional old Tbilisi scene. His drawings from this period were high-toned and expressive, and often contained images marked by dramatic and tragic elements. He depicted Stepko, who was a little later described by Knut Hamsun as a tavern keeper from Tbilisi that treated guests with particular dignity.

Sudeikin’s Georgian Poets were originally painted on the opposite wall. According to contemporary texts, it showed the members of the Blue Horn group in masquerade costumes along with the artists who had decorated Kimerioni. At the bottom of the stairs, the guests would pass through an arch covered with a theatre curtain that symbolically separated two different realities, take a turn to the left and enter the main hall of the café. Here they would be welcomed by another reality that was filled with Sudeikin’s mysterious, fairy tale-like, artistic images of cabaret dancers, clowns, guests at tables, chimeras, female magicians, baskets full of flowers and masks, as well as theatrical and nightlife scenes that were reflected in a broken mirror. The main subject matter of Sudeikin’s illustrations was the theatre, abundantly manifested in separate paintings, the hall decorations and attributes, and was specifically manifested in the features of the images. Grotesque, dreamlike, unreal, and occasionally very precise characteristic details were marked with a certain degree of estrangement and ambiguity.

Mural, Kimerioni, S. Sudeikin

Mural, Kimerioni, S. Sudeikin

At the same time, they all showed the beginnings of a kind of play and transformation. The main feature of the images is their “real” affiliation to the theatre: even in cases when a protagonist is presented standing on the stage, be it a clown or a dancer, the act of being on the theatrical platform is not manifested as the final goal of their actions, but rather related to their nature and essence. Accordingly, the viewers of the paintings developed a constant feeling of seeing them on an imaginary stage. The impression that they represent their own self as ballerina, as clown, as fairy, and as guests of the café contributes to Nikolai Evreinov’s concept of the “theatre for its own sake.” ... And this “imaginary stage” – an artistic space that creates an environment for the existence of all these images – is perceived as another reality, a transformed “theatrical” dimension.

Mural, Kimerioni, S. Sudeikin

Mural, Kimerioni, S. Sudeikin

This theatrical milieu created by Sudeikin became a meeting point for the members of the Blue Horn group, their friends and guests. The café offered up its space for exhibitions, concerts, and “aesthetic evenings designated for poets only”. The stage welcomed experimental performances by Nikolai Evreinov and Constantin Andron; the café even organized traditional wine-drinking feasts with impromptu recitals of Paolo Iashvili’s poems…

Artist and Muse, Kimerioni, David K’ak’abadze

Sudeikin’s decadent space also housed David K’ak’abadze’s work, the Artist and the Muse. It was painted at the end of the hall on the wall opposite the stage. Now it is only possible to see part of the drawing, since the image is intersected by a staircase. According to an old photo, the center of the composition focused on a pomegranate tree and female and male figures that were distributed in accordance with mirrored symmetry. A man – the artist, who can easily be identified as Paolo Iashvili, gives a scroll to the woman – a muse. Behind them we see a mountainous background that demonstrates a particular resemblance to K’ak’abadze’s Imereti landscapes. The frontal, strictly symmetric composition and its flat, simplified broken forms cover the surface of the wall like a colorful carpet. In characteristic cross-legged posture, the mannerism manifested in the bowed head and elongated limbs, as well as specific details of the garments and hairstyles, combine to create an overall poetic and artistic mood. The actions of the artist and his muse, together with their characteristic gestures, are clearly focused on the moment of the scroll transfer. All these details award the synchronous, schematic design of the painting a specific lightness and liveliness. In the main, metaphoric touches were added: the man – Paolo Iashvili – is enriched with the aspect and expressiveness of an artist; the woman is perceived as the image of a muse and inspiration. The transfer of the scroll before a mountainous Georgian landscape also serves as an artistic metaphor for the artist and his inspiration – his homeland.

Artist and Muse, Kimerioni, David K’ak’abadze (photo of the period)

Kimerioni was decorated by three artists – three artistic personalities. Each of them selected completely diverse topics for their works, and introduced their own individual moods into the space of the café. However, association of the paintings rhythm and harmony with the architecture, the compositional perception and general design of all three artists (anti-illusion of the images, clear and balanced distribution of the figures, clear lines, and local colors) managed to unite an entire set of decorations under one formal system. Three separate texts were connected to one another to form an extended narrative with one content: entrance as an introduction – Stepko’s Tavern on the one hand as homage to the other inns of Tbilisi and their unique features, while on the other hand the specific introduction of the “main characters'' dressed in masquerade costumes to the guests – preparing the latter for the atmosphere awaiting them in Kimerioni. The hall continued the plot’s development, and unfolded the whole diverse world of cabaret that draws us in and makes us part of the nightlife. However, despite its ephemeral and mysterious character, reality for the artist is revealed in the same way as it is shown in the metaphors of David K’ak’abadze. It is true that the mood of the hall was created thanks to Sudeikin, but the main focus of the content of the murals was suggested by the compositions of Gudiashvili and K’ak’abadze. The “visual narrative” begins with Stepko’s Tavern and ends with the Artist and the Muse. Sudeikin’s theatrical world merely becomes an integral part of this context, yet manages to do so without any conflict. All the themes that are united in this manner use the same common language. Their unity reveals one of the major concepts already suggested and confirmed in the texts of the Georgian Modernists. It focuses on national ideas and manifests the ideals of an artist and the purpose of his existence – described by T’itsian T’abidze as a “wageworker”. The unity also shows the nature of Tbilisi avant-garde, where artists of different ethnic backgrounds, ideologies and generations, with traditionally counter-positioned thinking, avant-garde forms of communication and lifestyles managed to coexist in a peaceful manner. It represents reality, described by Grigol Robakidze as a “fantastic aspect of Tbilisi”.