Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Throughout world history, the use of stained glass has been connected with the church and other religious facilities. For thousands of years, different types of glass were produced to animate or narrate Christian stories and illuminations. In the middle ages, during the high gothic era, yellow, red and blue were used extensively to bring more light into interiors, in order to make them more mysterious and bright. However, for a country like Georgia all of these experiments were out of range, mainly because Georgians didn't produce glass, and also because mosaic had held the leading role in illustration from the time of the Byzantine empire. Now, one can imagine what a significant process, in both political and creative senses, adopting the technique could be for an individual from a country which mostly produced its religious artifacts from stone, metal and wood. Such a person should already have attained not only the highest academic knowledge, but also the skills necessary to penetrate within the national form and its origins.

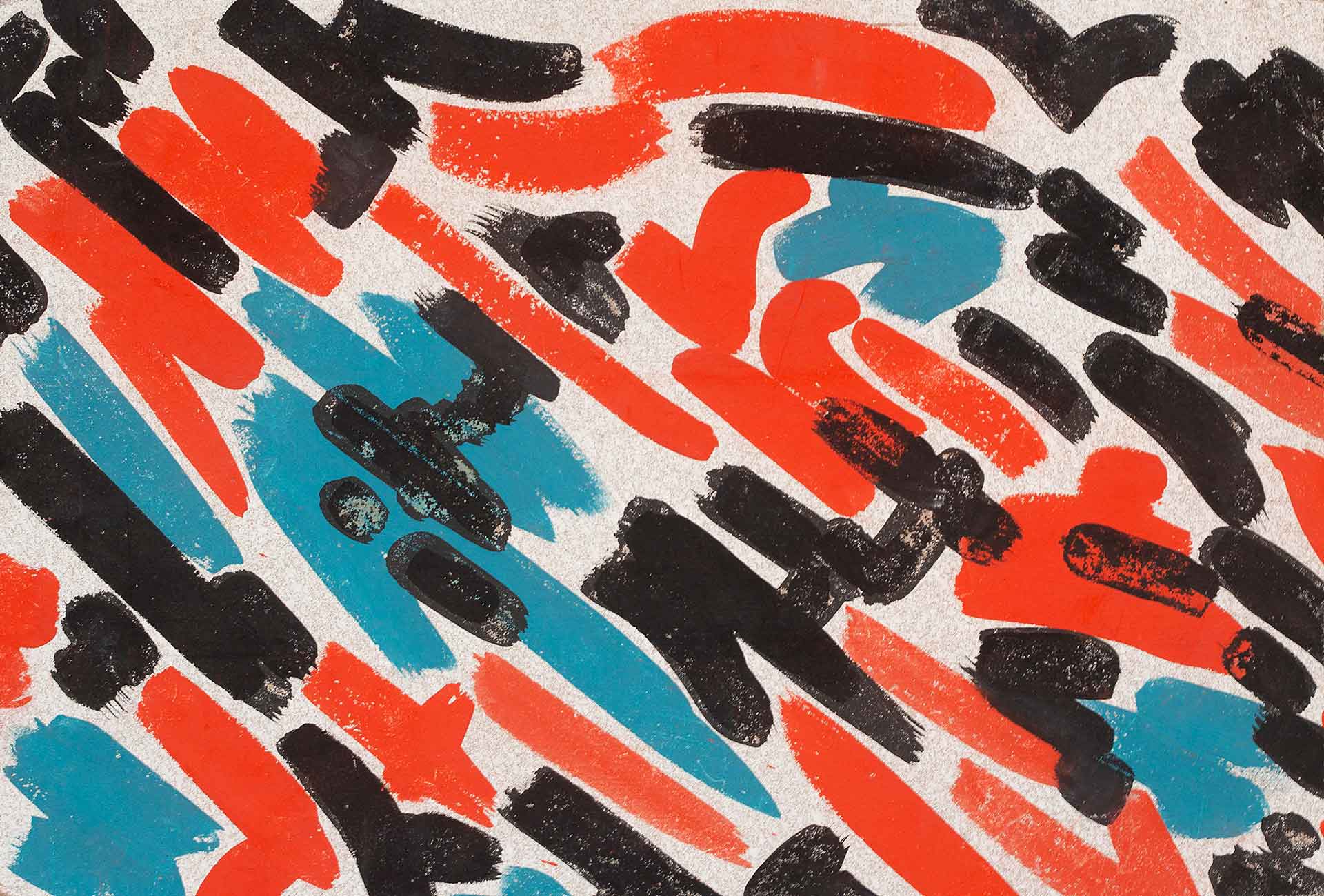

The story of Vakhtang Kokiashvili, who founded monumental Georgian art, goes back to the early 1950s when he attended the National Academy of Arts. However, he didn't fulfill the requirements established by the Soviet government and was expelled from the academy until, with the help of his father (also a famous and respected Georgian painter), he was again allowed to continue his studies. While attending the academy, Kokiashvili declared a great interest in experimenting with color and light. Even his student works: small scale abstractions, banners, and posters of different festivities, include splendid and lustrous reds, yellows, pinks and blues, among others.

V. Kokiashvili. Early works from Artist’s archive. 1960s

V. Kokiashvili. Early works from Artist’s archive. 1960s

Probably intuitively, but also intellectually, he recognized the necessity of new materials in Georgian contemporary art, which was already producing an excessive amount of paintings and mosaics that were mainly ideological in content, but were also created for decorative purposes.

Upon graduating from the Academy of Arts, Kokiashvili began working intensively on painting and later became the head of the National Committee, ignoring the established nepotistic order and helping hundreds of artists to realize their projects and ideas. As his daughter Nino Kokiashvili explains, “the idea and the concept were genuine for an artist [...], decorative works were viewed as less qualified; he preferred vision-driven images, based on intensive academic studies and research”. From this standpoint, one can already relate Kokiashvili’s art to the founders of Georgian modernism, David Kakabadze, Lado Gudiashvili, and Kiril Zdanevich among others. Back in the 1910s when Tbilisi’s avant-garde was established, they made it clear that the national form would be something eclectic, consisting of a tradition and transitory forms and movements. By tradition they meant the essence of the objects and forms found throughout Georgian culture, while the renewal provided them with new forms and media. In such a way, the Georgian avant-garde as we see it now was established through a pluralistic renaissance pathos, giving way to the most remarkable of hybrids and a diversity of artistic subjects.

On one occasion, Kokiashvili visited Notre-Dame de Paris. As his close friend Elguja Berdzenishvili later recalled, he praised the stained glass windows. Upon leaving the cathedral, it was already clear that Vakhtang had found the perfect medium for establishing his fundamental concepts and ideas. After that, glass became an inseparable part of the artist’s life. It consumed all of his time and energy (because the glass was not produced in Georgia). The output was also enormous: his works were installed throughout the entire country, and afterwards expanded through the other Soviet Union republics.

Interior and stained-glass panel. Hotel “Iveria”. Tbilisi. Georgia. 1967

It remains obscure how the artist, in such a hermetic space as the Soviet Union, managed to experiment on such deep cultural levels, preserving both the tradition of Georgian form and French gothic art, while at the same time reinventing them. We can speculate that Soviet realism was based on the foundations of the avant-garde. Nevertheless, the Soviets condemned formalist experiments, since in their opinion everything should become social (secular), while describing the ethno-economic activities of a given culture. The form had to be national and the content had to deal with socialist ideas. All the same, Kokiashvili succeeded in creating the most brilliant synthesis between the qualities of gothic glass and Georgian national form.

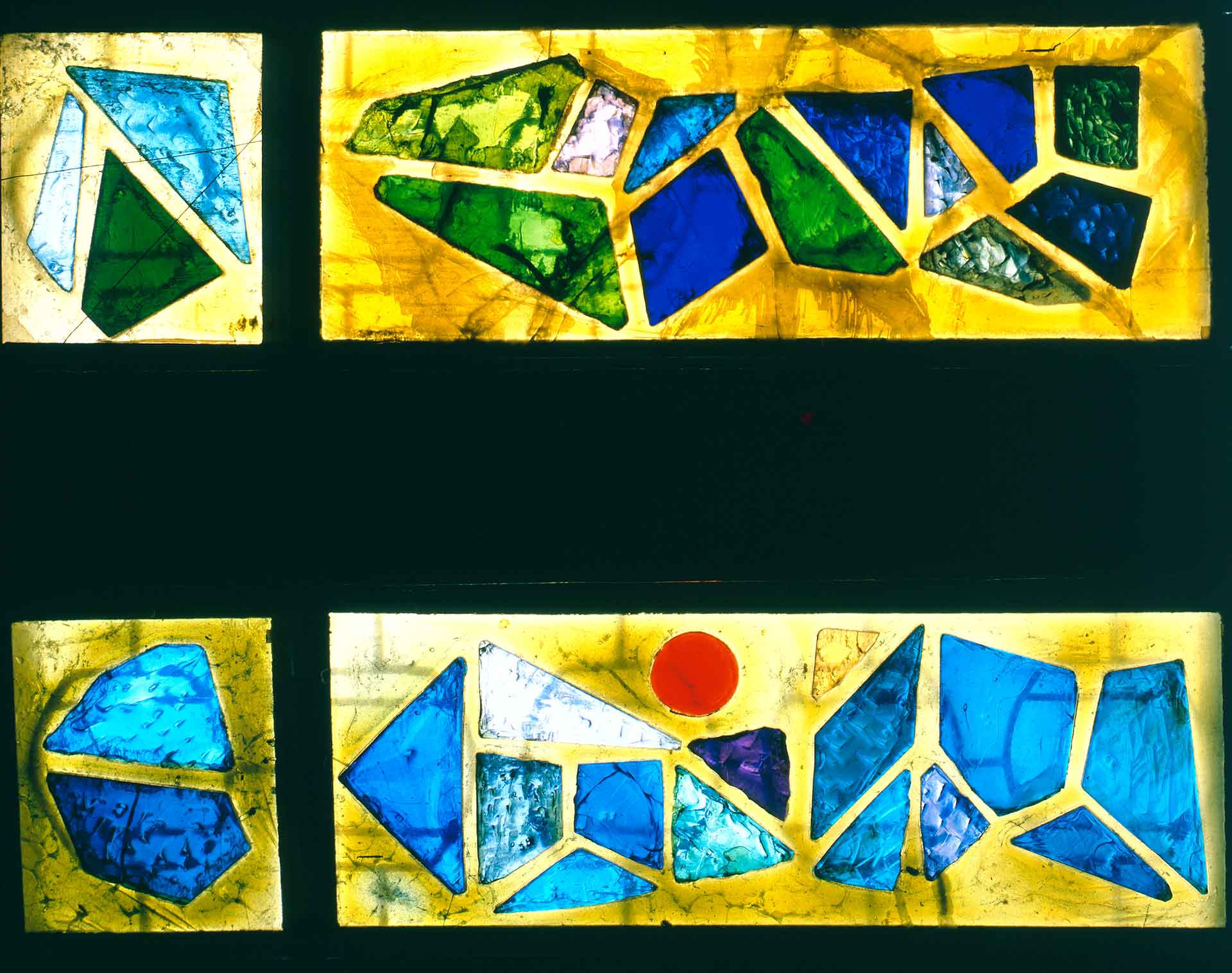

Decorative stained-glass panel. Abasha. Georgia. 1978

In order to carry out such an experiment, he needed to figure out not only the narrative of his works, but also the concrete materials necessary for remodelling. Detaching gothic tradition from the church would already transform its religious and physical qualities. For churches, especially for high gothic examples, the tall buildings required different characters of light, shade and even glass. The brightness in a high gothic church such as Notre-Dame, achieves an almost illuminating presence of a human being inside. But the buildings Kokiashvili designed were meant for secular and profane functions (like hotels, cinemas, restaurants, airports, etc.) This was not something new for the Soviet ideology, they had already been designing social facilities for a long time. Among them the media of communications (in the wider sense) were most important. Train and bus stations, funiculars, airports, metropolitan railway stations, etc. everything that had an immediate and unconscious effect on the people should reflect the ideological presence of the existing order. In such a fashion, the Soviets designed the whole of reality and reality as a whole. To transcend the boundaries of the established order, Kokiashvili used both profane and sacred materials, as well as the codes available in Georgian culture that are mainly found in abstractionism, much as in western art (artists such as Pollock and Rothko inspired him for a long time).

Stained-glass panel. “Berikaoba”. Lower station of funicular. Tbilisi. Georgia. 1970-1971

Stained-glass panel. “Berikaoba”. Lower station of funicular. Tbilisi. Georgia. 1970-1971

For the narrative he typically chose either ethnographic, or cosmic and abstract subject matter. Such a transformation maintained certain qualities of the stained glass concept, through which religious stories were narrated. With this experiment, Kokiashvili accorded the glass a social function based on the insights of the industrial city, for people who were tired from working in the fast lane and were looking for some sort of relaxation in restaurants, cafés, hotels, and other places. In this way, through the meditative presence of ethnographic, cosmic and abstract narrations, they could escape their daily routine. Kokiashvili’s glass works may no longer attain an illuminating effect, but they transcend the everyday social experience; the banality of time is transformed into a levitating presence of lights, shades and colors.

Interior and stained-glass panel. Hotel “Iveria”. Tbilisi. Georgia. 1967

Interior and stained-glass panel. Hotel “Iveria”. Tbilisi. Georgia. 1967

He gave a new, industrial meaning to French stained glass, and endowed it with contemporary needs – those of rest and escape. Later he combined the glass with plastic, opening up wider social dimensions that could be accessible to modern human sensuality. Another technical innovation that must be considered are his multi-layered glasses. When we look at his works, we notice the multi-dimensional field they create. Such a quality was chiefly attained by understanding the depth of the form and the material, while also studying and meditating on cosmology. Colors played a huge role in the artistic development of the stained-glass. While blues and reds were preserved from the gothic tradition, for example, amazing yellows and greens were added to the structure, which through the complex and polyhedral forms of the metalwork established a new foundation.

Decorative stained-glass panel. Beer bar. Kutaisi. Georgia. 1978

Through this experiment, Kokiashvili created immanent forms that were oriented inwards. Thick and translucent glass imbued the interior with an intimate atmosphere. One could experience the feeling of getting away, escaping from the ordinary world, which due to its industrial turnover was becoming hectic, automated and overly visible. At the same time it made possible cosmic escalations. Removed from the city’s constructions, the soul once again found inner movement and peace. In such a fashion, Georgian gothic was born.

Decorative stained-glass panel. Hotel. Zugdidi. Georgia. 1984

Nowadays, Kokiashvili’s art remains in the shadows. Most of his stained glass works were destroyed. Today only two of them remain complete. Another massive work that was removed from the Tbilisi funicular is currently stored in a damaged state in a warehouse. To restore and preserve this legacy means not only the preservation of Georgian culture, but also the rescue of a universal experiment, which might completely change our understanding of contemporary art, its philosophy and function.