Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Tamar Abakelia (თამარ აბაკელია) was one of the most successful female artists of the first half of the 20th century – in the 1930s and 1940s. She was a multi-faceted creator: a sculptor, graphic artist, painter and illustrator, a theater and film painter, and finally, a socially and creatively active individual with a strong character.

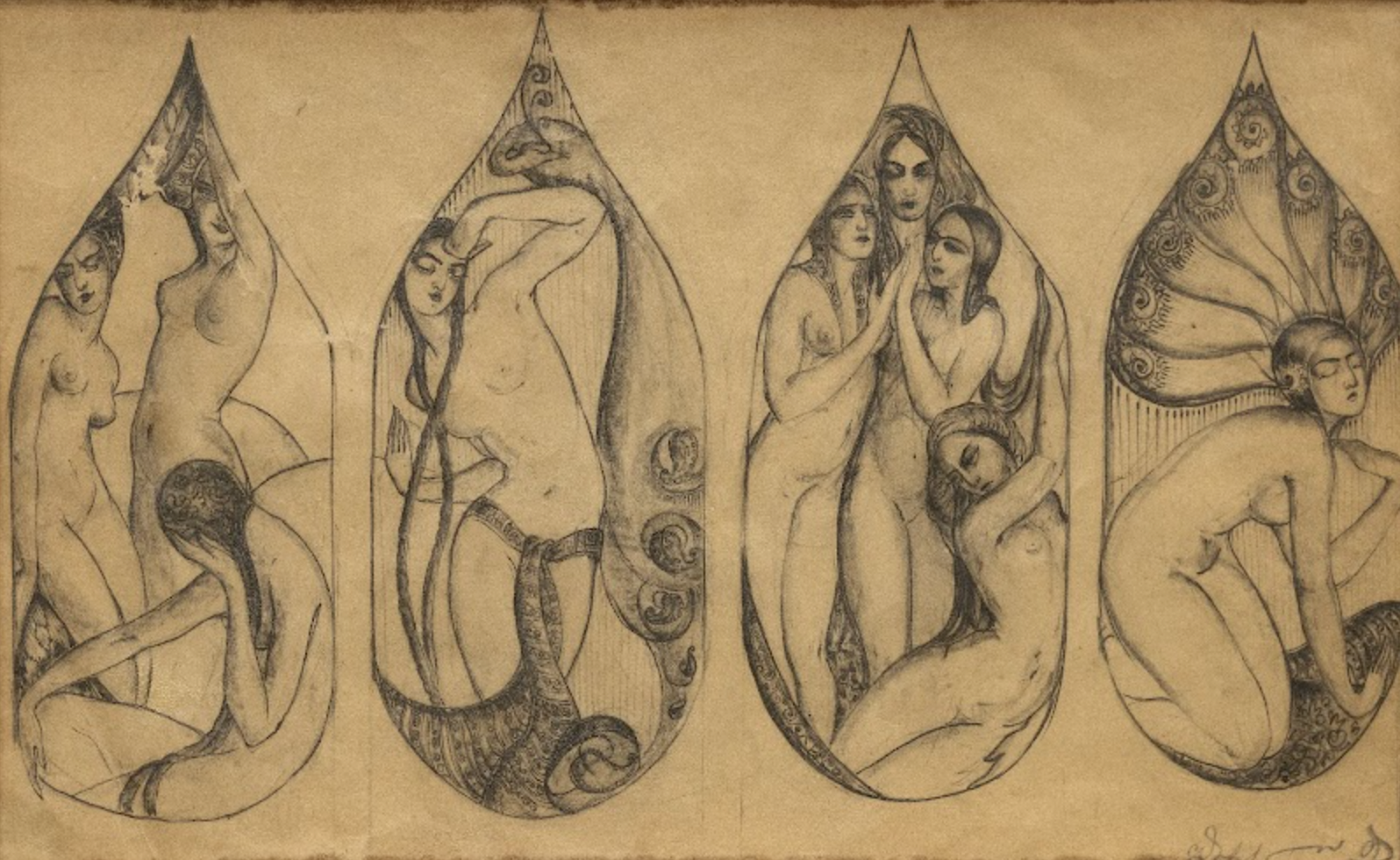

Tamar Abakelia. Untitled. Pencil on Paper. 13.5x23 cm. 1930s. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Tamar Abakelia was born in Khoni in 1905. The future artist grew up in western Georgia, but also spent several years in Odessa. She began painting and sculpting as a child, and decided to enroll at the Faculty of Graphic Art at the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts as soon as it had been established. While there, Iakob Nikoladze soon noticed the young woman's talent for working with plastic and monumental shapes, and invited her to his workshop. From then on, sculpture became an even higher priority in the artist's work. After graduating from the Academy of Arts in 1929, in parallel with painting, Tamar Abakelia continued to work in the field of monumental sculpture alongside Georgian sculptors. Among many other famous works, she authored the relief frieze that featured on the façade of the Georgian branch of the Institute of Marxism-Leninism (now the Biltmore Hotel), and produced work that is considered to be a precondition for the revival of the Georgian relief tradition. Along with the creation of sculptural works, beginning from the 1930s, Tamar Abakelia started to work intensively on book illustrations and scenography. She died in 1953 at the age of just 47.

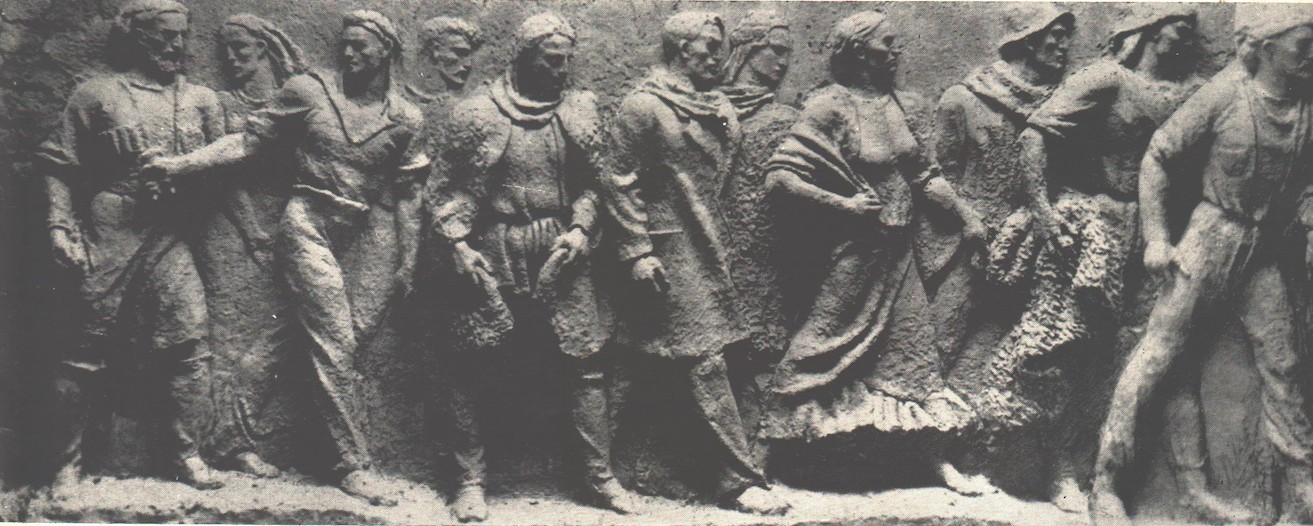

Details of the bas-relief of the facade of the Imeli building. 1936.

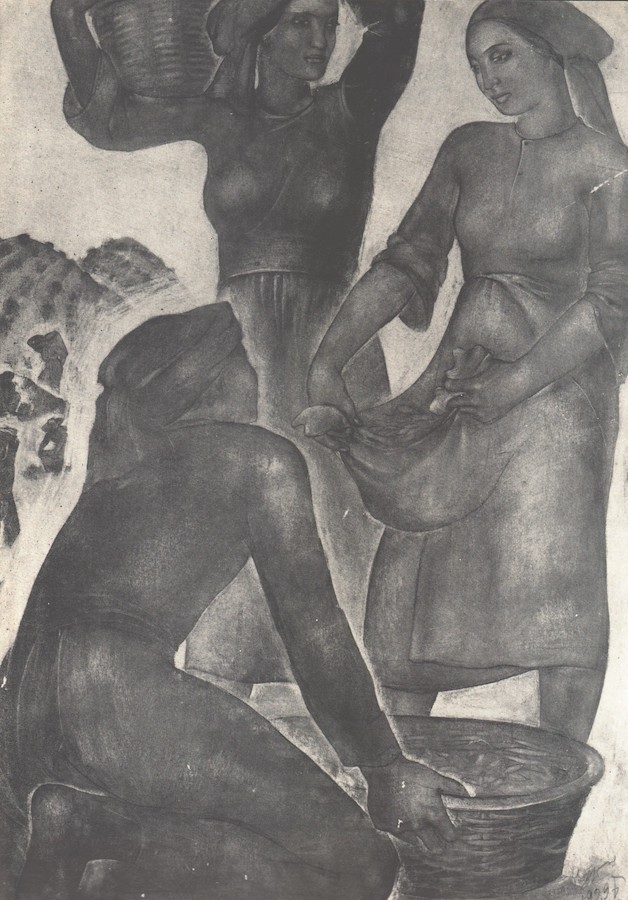

Tamar Abakelia. Tea Picking. Paper, sepia, watercolor, sangvina. 1929.

Notwithstanding the Soviet reality and the conjuncture of social realist art, beyond poster compositions Tamar Abakelia conducted earnest creative research in two main directions: firstly, Classical and Renaissance forms; and secondly, the plastic shapes and rhythms of Ancient Art. It is easy to observe these artistic and stylistic trends in Abakelia's graphic works and relief friezes, where her compositions evoke distant associations with the multi-figure frieze scenes from antiquity. However, the most interesting fact is that, unexpectedly for the realities of that time, Tamar Abakelia's work focuses on female characters and women in general.

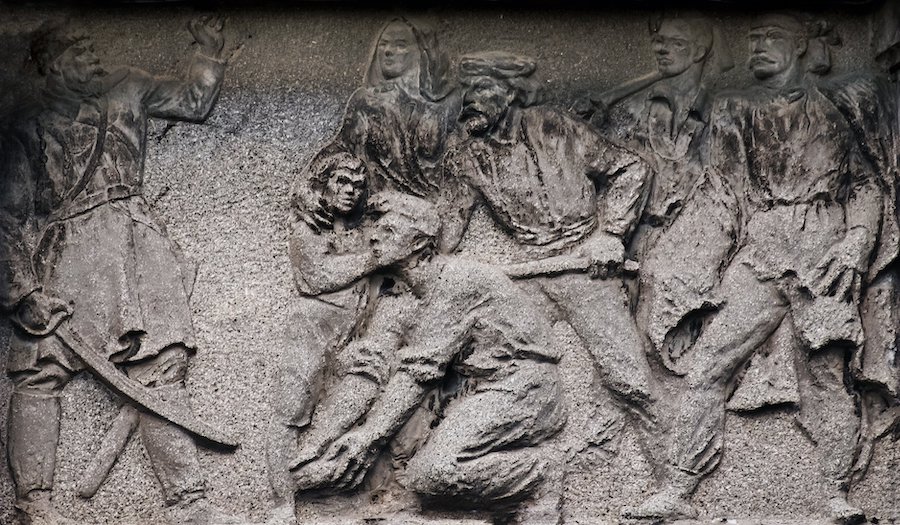

Bas-relief of the Adjara Art Museum. 1951-1952.

Tamar Abakelia's paintings and sculptures clearly present the image of a strong, independent, energetic individual who is equal to a man, and often even superior. These images only partially met the requirements of Soviet art, and in fact came into conflict with it. Masculinization of the female image by Soviet realism was not so much about the demonstration of equal rights with men, rather than a clear canonization of the art of labor exploitation by means of a propaganda machine. Tamar Abakelia seems to employ the dogma of socialist realist art and the demands made upon artists by the Soviet Union to her advantage, and creates the image of a strong and independent, moreover sexually appealing woman that ventures beyond the banal characterization of a happy Soviet citizen.

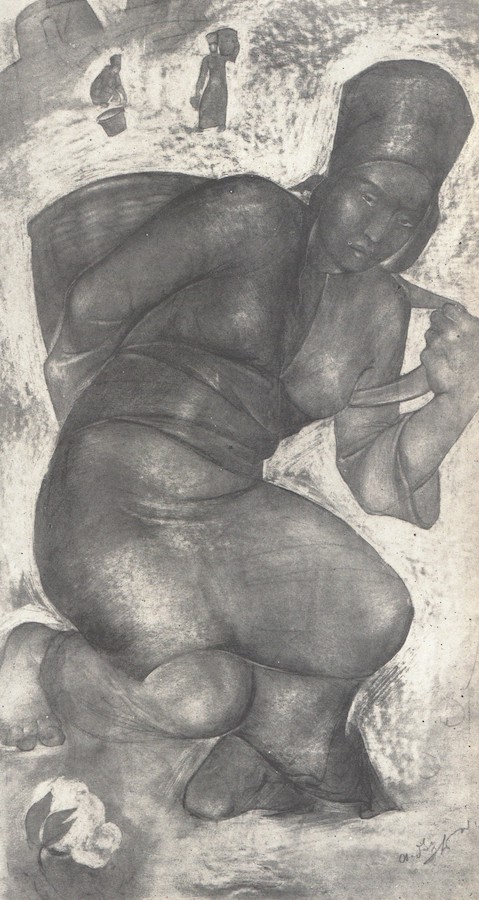

Tamar Abakelia. Cotton Picking Turkmen Woman. Paper, sepia, pencil. 1932.

This is particularly visible in the sculptures and graphic works dedicated to the topic of collective farms and the family unit. A typical Soviet sculpture, and one can even say stereotypical three-figure group of the “Family of the Collective Farmer,” with its storyline and composition pushes a female figure to the foreground, thus transforming her into the main character. A woman forms the axis and compositional apex of a sculptural group that is designed for frontal perception. The gazes of the male figures manifest veneration and respect – the need for a mother; while the woman’s appearance displays courage and headstrong independence – features not so common or permitted during the Soviet era. The posture and the facial expression of the female figure do not show any special emotional connection with the members of her "adorable family." On the contrary, she emanates a certain inner distance and inner freedom.

Tamar Abakelia. Family of Collective Farmer. 1939

Tamar Abakelia. A Happy Family. Paper, pencil, watercolor, Indian ink. 1936.

In the graphic work Picking Oranges, a woman is seen with lowered eyes, a slightly unfocused gaze, a provocative manner of standing, and above all, breasts that are visible under her tight clothes, which violate all Soviet norms – being excessively attractive and sexually appealing. Especially since this is neither natural, genuine charm nor subtle sensuality, but sexuality which is well-thought-out by a woman, and turned into a provocative tool in her hands: body language of communication that a female artist has specifically selected for her female character.

Tamar Abakelia. Picking Oranges. Paper, sepia, pencil, watercolor. 1932

In this way, Tamar Abakelia frees the charming woman from being the subject of detached contemplation or desire, and does not allow her to be turned into an object – an act quite unusual and bold for a female artist emerging from the Soviet context.

Tamar Abakelia is author of one of the most famous war sculptures of Soviet Georgia, “We Will Seek Revenge!” (bronze, 1944), where the main character is again a woman. According to the author herself, “This is not a weeping mother, but a dangerous, vengeful Soviet woman.” A massive, gloomy, seemingly sexless, accentuated masculine figure with a grim facial expression makes a mournful impression on its viewers. The unyielding face of the silent frowning woman, her body with straight spine and shoulders that is taking a step forward express feelings of threat, readiness and desire for revenge. The figure was designed for frontal viewing, and has a pronounced mood of proffering. A mother whose child has been killed moves in our direction to show us the tragedy of brutal war and an innocent victim, to turn us into sympathizers and call us to join her in revenge. In this way, Tamar Abakelia creates a clear individuality: the image of a strong woman who is an active subject with the power to engage in battle on her own, and even lead it. As Tamta Melashvili points out, “her works were different from the passive propagandistic images of the Soviet women we knew from the beginning of WWII. She did not depict them as victims that had to be protected by men and their homeland. Abakelia's 'vengeful' woman was a subject and an agent who resisted the enemy by herself.” However, the artist sacrificed the paradigm of her precious classical art to achieve this. Strange as it may seem, Tamar Abakelia - aficionado of Renaissance art - created a complete reverse reflection and antipode of Michelangelo's Pieta.

We Will Seek Revenge. Bronze. 1944

Accordingly, one can say that through her work Tamar Abakelia created and established in Georgian fine arts the image of a strong, independent, individual woman who is equal to man and often even superior to him. This was a well-thought-out and purposeful act of a successful, socially and creatively active artist, as well as an important concept of the author’s own art. Tamar Abakelia managed to bypass the dogma of socialist art and its primitive and trivial format so as to create thematic storylines that would focus on women with individual inner worlds.

Tamar Abakelia. Costume sketch for Georgian song and dance ensemble. Paper, mixed technique. 30x23cm. Late 1940s. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

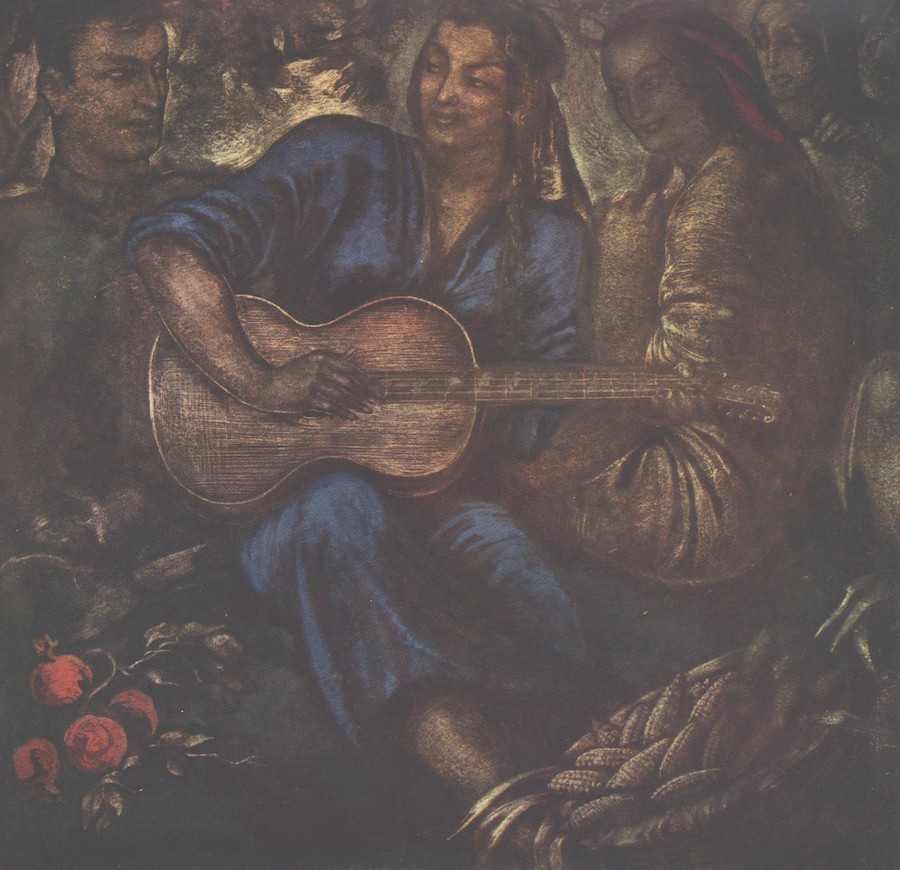

Tamar Abakelia. A Song to the Hero. Paper, watercolor, Indian Ink, gouache. 1945.

Tamar Abakelia. Good News from the Front. Paper, watercolor, Indian Ink. 1943.

One of the best ways to become familiar with Tamar Abakelia's personality and to understand her work is to read the artist's diary, which she wrote almost all her life, from 1919 to 1953 – the year of her death. While still a young woman aged 17-18, she wrote in her diary “I, a weak woman, have only one force - hope, faith and dreams.” A little later she wrote that “I did not sense a real creative life before entering the academy. I suffered from distrust towards my own strength and often cried because of it.” Such records show that Tamar Abakelia underwent a rather difficult path of personal development. Apparently, her personal experiences inspired the artist to populate her own creative world with strong women, and thus prove skeptical audiences mistaken regarding the so-called weaker sex.