Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

The custom of erecting crosses in Georgia traces back to the time of Christianization of the Kingdom of Kartli in the 4th century. According to Georgian church tradition St. Nino, who converted Kartli to the new faith, put up wooden crosses in place of pagan idols to symbolize the country’s Christianization. Mirian, the first Christian King of Kartli (the kingdom in eastern Georgia), set up wooden crosses on Mount Tkhoti, in Bodbe and in Ujarma. Over the course of centuries, wooden crosses were replaced by crosses made of stone. Monumental stone crosses, particular cult objects, demonstrate the importance of the veneration of the Cross in the spiritual life of Georgia. Numerous fragments of stone crosses and depictions of these cult objects give us a clear idea of their structure. The earliest depiction of a stone cross is preserved on the east façade relief of the 6th century Edzani Church. The relief clearly shows a stepped pedestal, a quadrilateral stone pillar carved with reliefs, an ornamented capital terminating in a model of the Holy Sepulcher, and a sculpted stone cross at its top.

Relief image of Stone Cross. Edzani church. East façade. VI c.

Stone crosses covered with carved decorations are mostly dated to the 6th-7th cc. The main center of production was Kvemo Kartli (or Lower Kartli, the south-eastern part of Georgia), where numerous workshops were active. The bases of crosses survived in situ, demonstrating that the traditional place designated for their installment was at/near the south-west façades of churches.

Subjects from the Old and New Testaments, symbolic representations and ornamental patterns created meaningful relief programs of the crosses. Portraits of the commissioners were also carved on the pillars of the stone crosses. Compositions strong salvation symbolism prevail in the decoration of these monuments. Usually three of the four sides of stone cross pillars are covered with carved illustrations, while the fourth, eastern side either is left plain, without decoration, or is covered with ornaments.

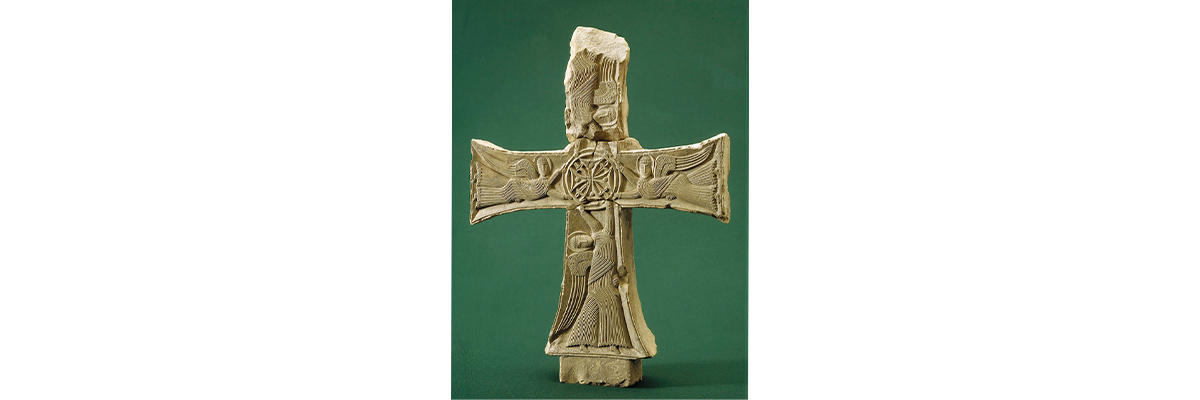

Stone Cross. Khandissi, VI c.

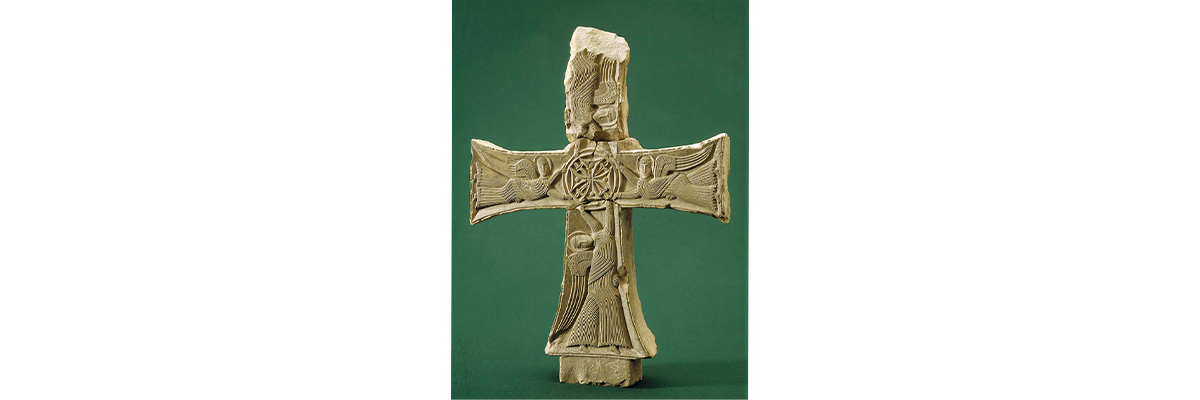

The decorative systems of crosses are structured in accordance with Christian hierarchy - the Glory of Christ or of the Virgin are depicted at the top of the pillars. They are followed by various compositions from the Holy Scriptures: i.e. Daniel in the Lion's Den, Abraham`s Offering, The Fall of Man, the Annunciation, Nativity, Baptism, Entry into Jerusalem, Crucifixion, and the Holy Women at the Sepulcher. On several stone pillars (Khandisi, Brdadzori and Naghvarevi) in the upper, “heavenly” register, the Ascension of Christ is depicted.

Ascension of Christ. Stone Cross. Brdadzori. VI.c.

The capital of the Brdadzori stone cross displays an original composition of the Assumption of the Virgin, where the soul is represented as a small swaddled figure held up by two angels. On the pillar from Natlismtsemeli (the Monastery of St. John the Baptist) in David-Garedji, the miraculous vision of St. Eustatius is depicted, emphasizing the pagan general’s conversion.

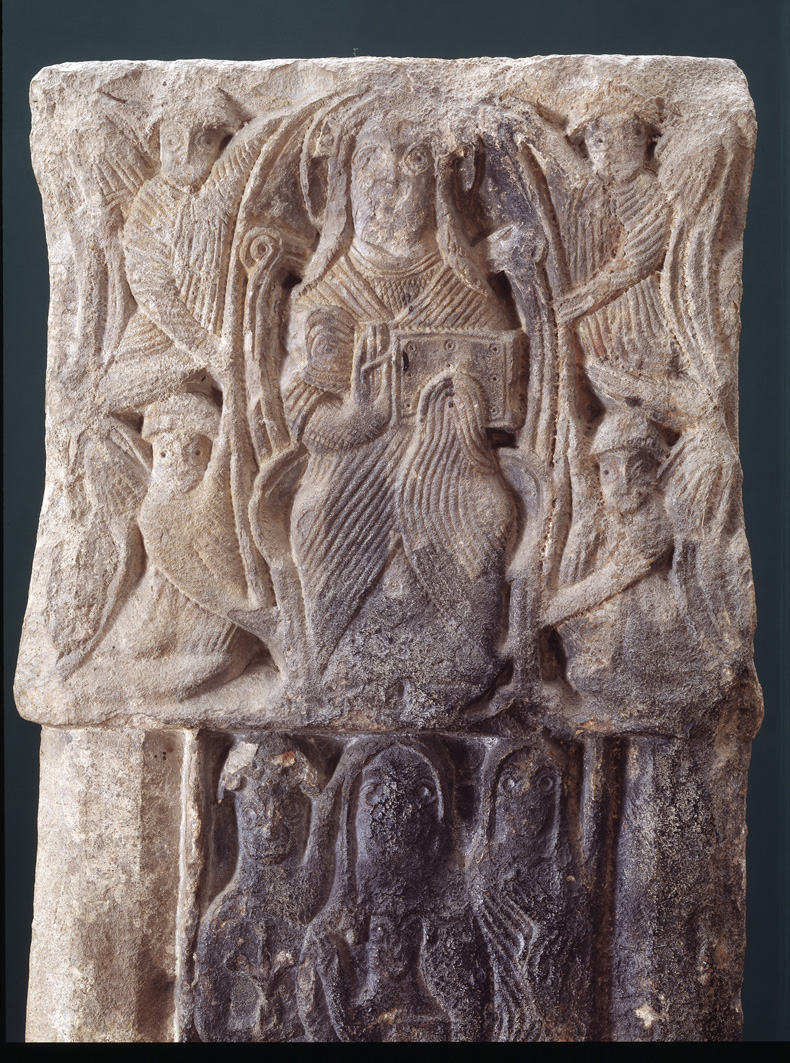

Natlismtsemeli. Stone Cross. Dmanisi. VI c.

Floral patterns prevail in the ornamentation. Crosses inscribed into medallions of stylized vegetal motifs are widely used on different parts of the crosses. The stone pillars are often topped with a model of the Holy Sepulcher, which is represented as a small arched structure.

Representation of the Holy Sepulcher. Stone Cross. Khandissi VI c.

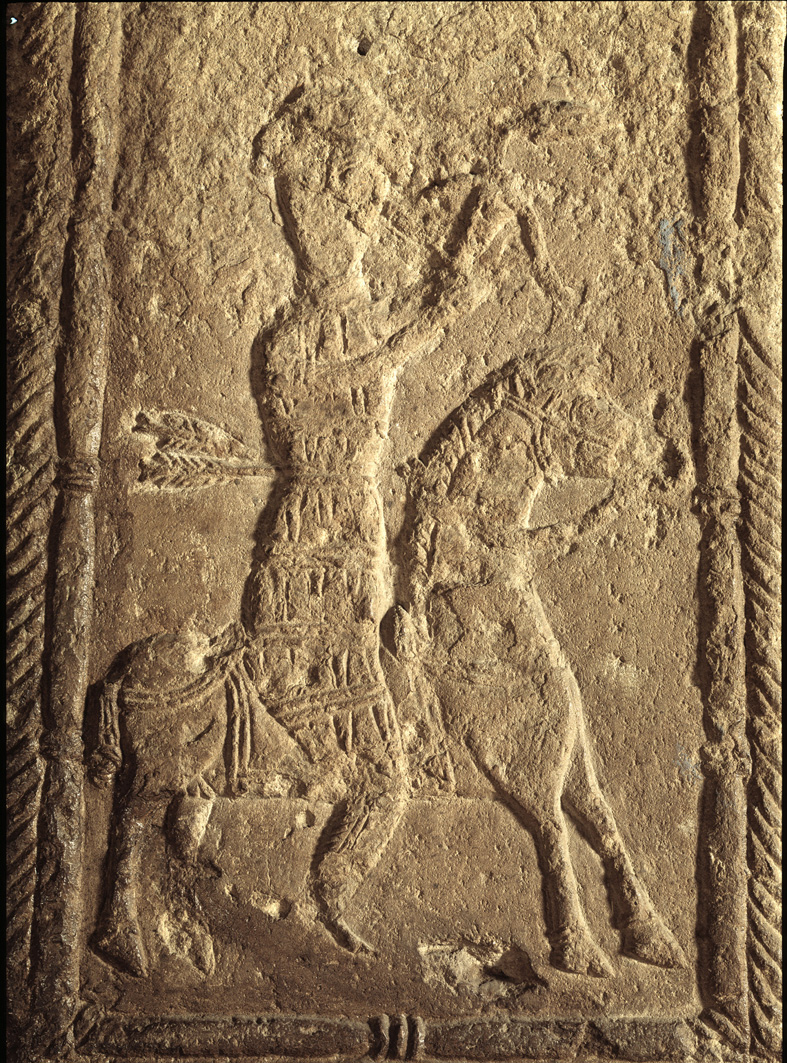

The relief programs of the stone crosses also include the ‘portraits’ of commissioners, who were predominantly Georgian noblemen. Rather conventional, schematized relief ‘portraits’ adorn the sides of stone pillars from Dmanisi, Bolnisi, Brdadzori, Davati, Kataula and Balitchy. The sculptural decorations of monumental Georgian stone crosses offer insights into the early medieval artistic world. Artistic and aesthetic affinities with East Christian culture displayed on the crosses testify to the intensive contacts between Georgia and its neighboring countries. The selection of narrative and symbolic compositions depicted on the stone pillars of the crosses proclaimed the Christian teaching and its main dogmas. The monumental stone crosses also had considerable political overtones, since they manifested their commissioners’ power and status.

Stone cross from Davati, VI c.

In later periods, the fragments of damaged stone crosses were inserted into churches as effigies of the historical past. Relief fragments with images and compositions were perceived as stone icons, placed in the semantically charged elements of the interior – near the sanctuary, and/or at the entrance. There are cases when panels with reliefs were used on church façades. The preserved material enables us to conclude that the tradition of erecting stone crosses in Georgia lasted until 8th – 9th cc.