Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

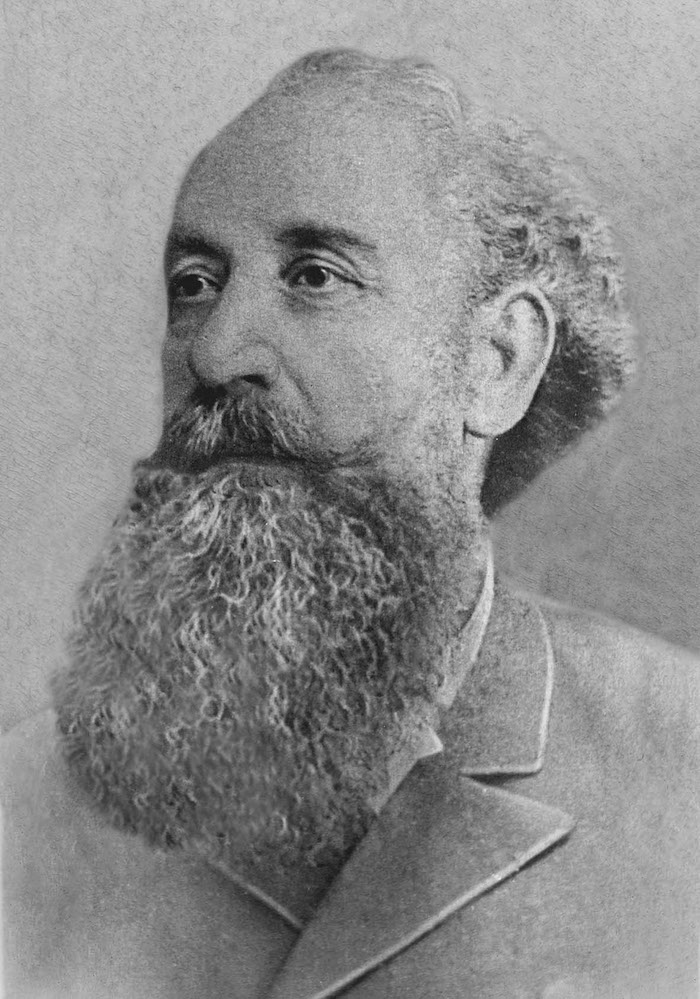

The renowned opera singer Filimon Koridze returned to Tbilisi from Italy in 1880. According to press archives from that time, Filimon had enjoyed a successful career with various Italian theaters, including La Scala in Milan. He returned to Tbilisi at the invitation of the local Opera Theater. When he was about to return to Italy, he was visited by a number of Georgian singers who inquired whether it was possible to transcribe Georgian chants into musical notation. Filimon agreed: "They came, they sang, I converted the chants into notes; I sang, and I also played the chants on the piano. Then they became convinced that Georgian chants could be transcribed into notes," was how he recalled the story of that first meeting, news of which spread rapidly throughout Georgia.

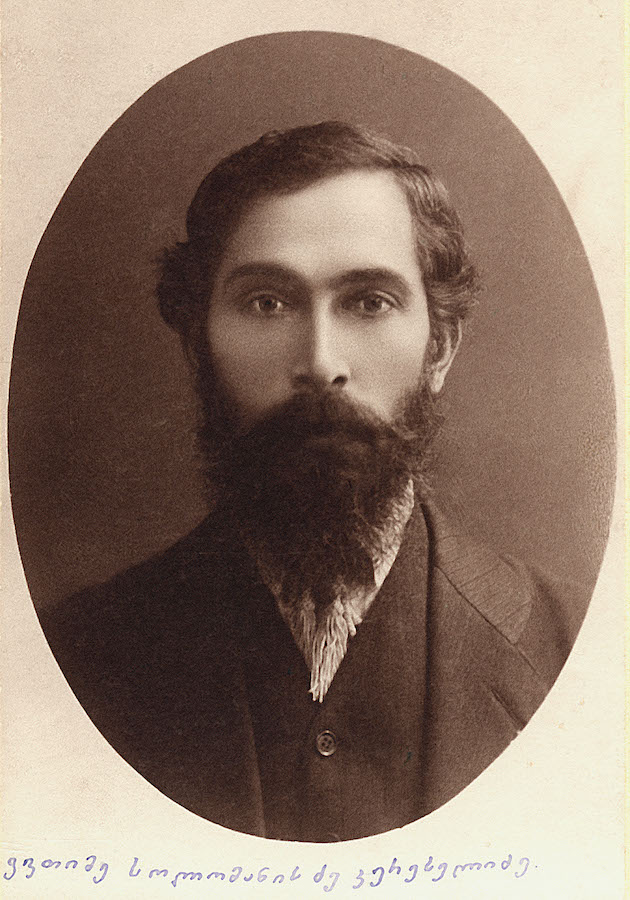

Filimon Koridze

The expert chanters Nestor Kontridze, Melkisedek Nakashidze, Ivliane Tsereteli, and other singers often visited Filimon. He enjoyed transcribing the unique chants into musical notes. This work became so important to him that he abandoned his professional singing career with the Opera House, and never returned to Europe.

This historical event turned out to be not a moment too soon for Georgian chanting, which by that time was already in a desperate condition. After Russia had abolished the autocephaly of the Georgian Church, the centuries-old traditional Georgian chants seemed to be on the verge of vanishing completely. By order of the Russian Synod, divine service in Georgian language was prohibited. Georgian chants were no longer used during the liturgies that were held in Russian language, and no attention was paid to their study. Georgian chants were disparagingly likened to "goats shrieking" or "dogs barking" by Russian exarchs. Traditional chanting schools at churches and monasteries were dissolved. Soon there would be no one left to teach singing.

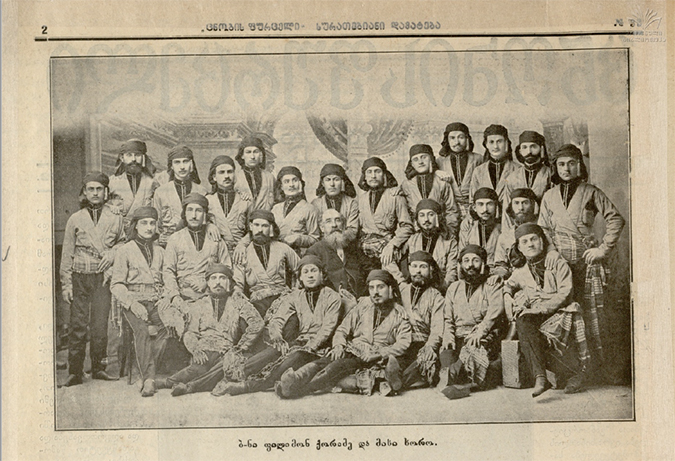

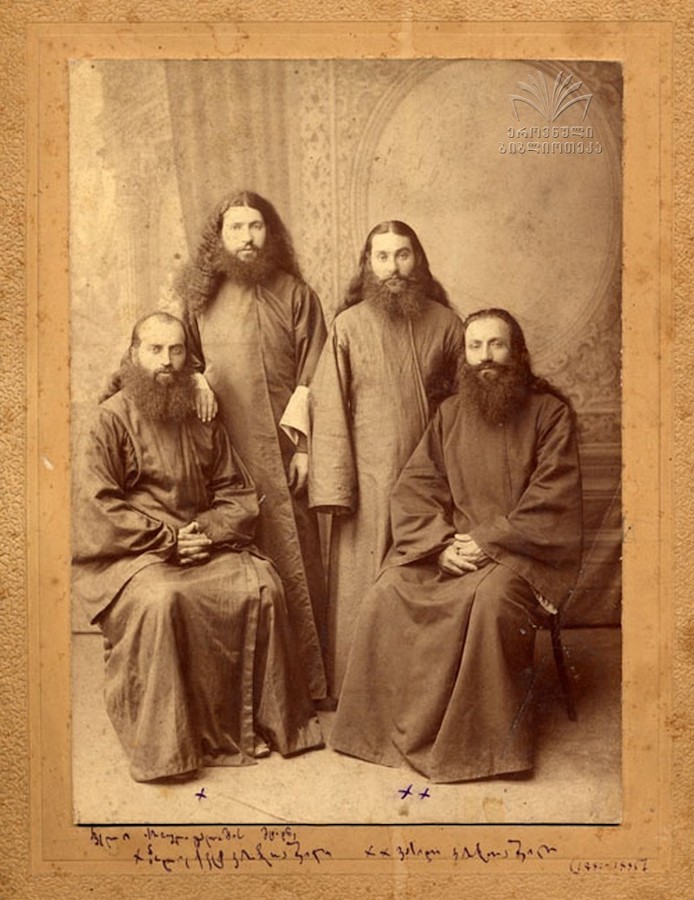

Filimon Koridze and his team. 1902

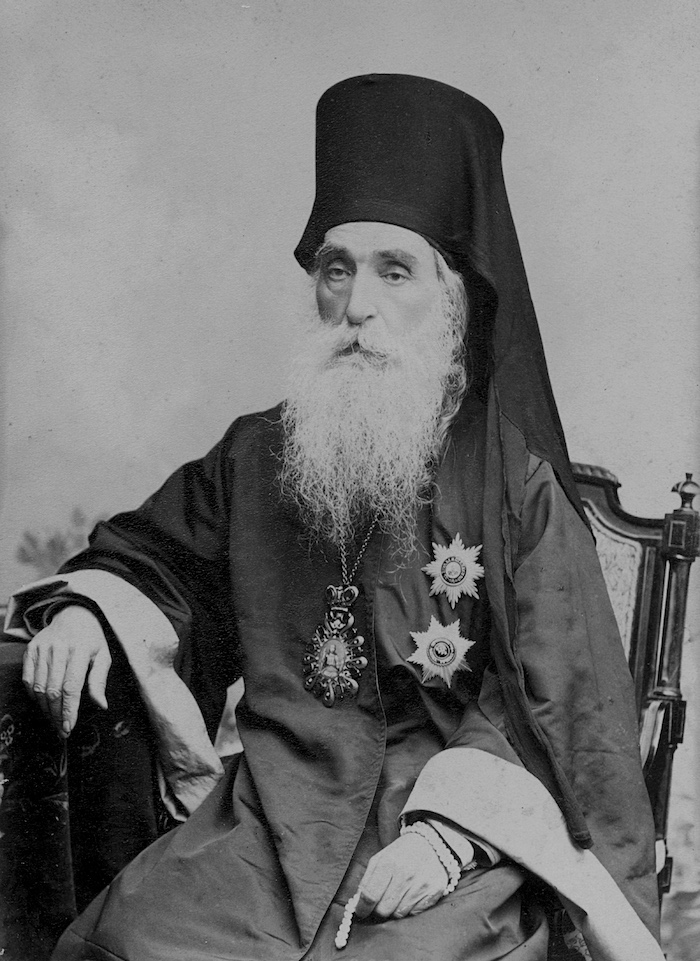

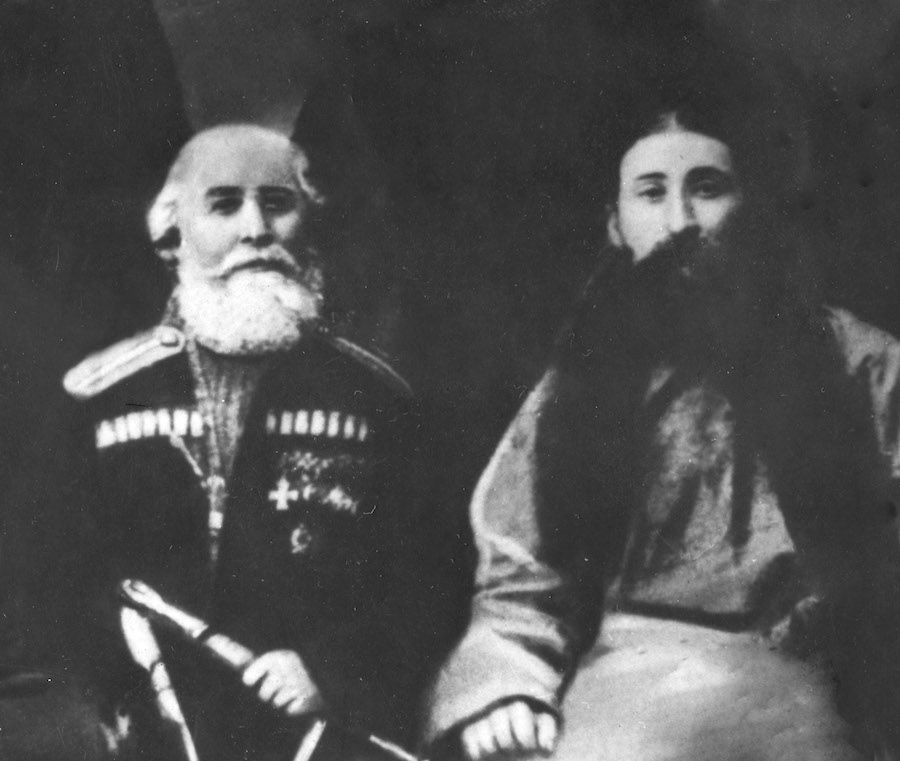

Georgian clergymen spent much time deliberating how to resolve the existing situation. In the 1860s, under the leadership of the public figure Bishop Alexander Okropiridze, a committee was established to restore chanting in Tbilisi. There were certain successful efforts to record the chants. The work of the committee was hampered by the Russian Exarch Pavle and the Rector of the Theological Seminary, Chudetski, as well as by the controversial opinions of Georgian society on certain issues. The Georgian chanters disliked the chants of John Chrysostom's liturgy that were recorded by Mikheil Machavariani, a teacher at the Tbilisi Theological Seminary. Bishop Alexander also refused to take the position of chair of the committee, although he continued to support Georgian chanting.

Bishop Alexander Okropiridze

The arrival of Filimon Khoridze in Tbilisi at this time contributed greatly to the salvation of Georgian chanting. The Georgian patriots undoubtedly found it difficult to realize they were doing something so historically significant that it would be valued a century later.

The Bishop of Imereti, St. Gabriel Kikodze, promised to help Filimon Koridze. The local clergymen and parishioners even collected money and arranged for famous singers from Kutaisi, Western Georgia to meet with Filimon: Jaba and Telemak Gurieli, Anton and David Dumbadze, Melkhisedek Nakashidze, and Nestor Kontridze from Guria; Dimitri Chalaganidze from Samegrelo; Niko Medzmariashvili, Nikoloz Kandelaki, Razden Khundadze, Tarasi Tkeshelashvili, Ivliane Shotadze, and Vasil Kutateladze from Imereti; Andria Benashvili led the episcopal team.

The Bishop of Imereti, St. Gabriel Kikodze

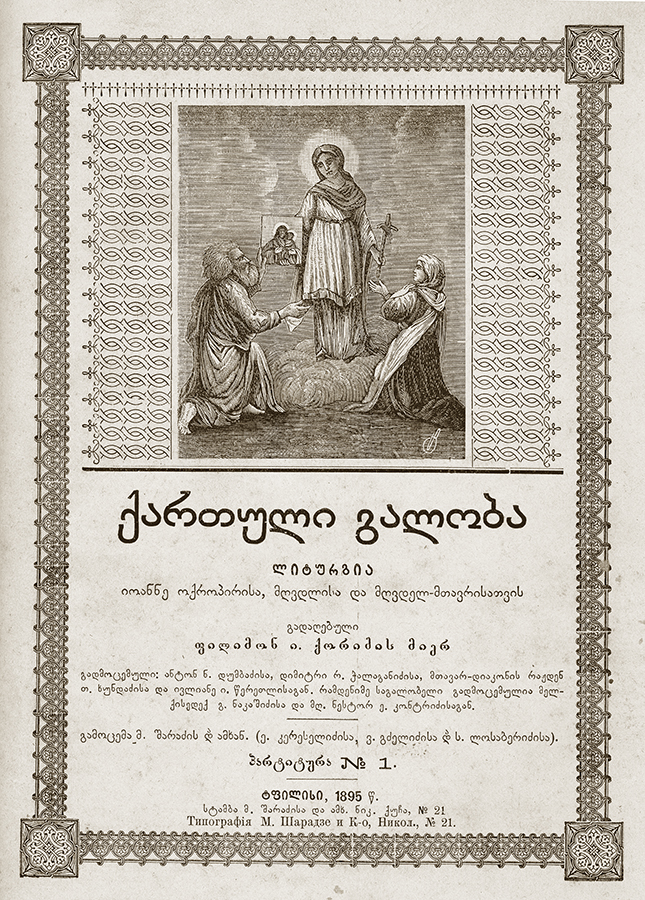

With this support, between 1885 and 1886, Filimon Koridze recorded 400 chants from the liturgies of Basil the Great and John Chrysostom. However, the funds required for the publication of 560 manuscripts still had to be found.

The right man at the time, Maksime Sharadze, appeared unexpectedly. He was an employee of the "Iveri" newspaper, which had been founded by the leader of the 19th century national liberation movement, the writer and public figure Ilia Chavchavadze, whose friendship proved to be an invaluable contribution to the survival of Georgian chanting.

Maksime first established an "office for reading divine literature" in Tbilisi, and later a printing house. Maksime heard the famous chanter Melkisedek Nakashidze and his choir performing chants in Kashueti Church, and he remarked, "I was touched and I began crying; it turned out to be so sweet." Cordial relations with famous singers inspired him so much that he learned notes from Filimon Koridze, and then Ilia Chavchavadze helped him to obtain a musical typeface and a typewriter from Germany.

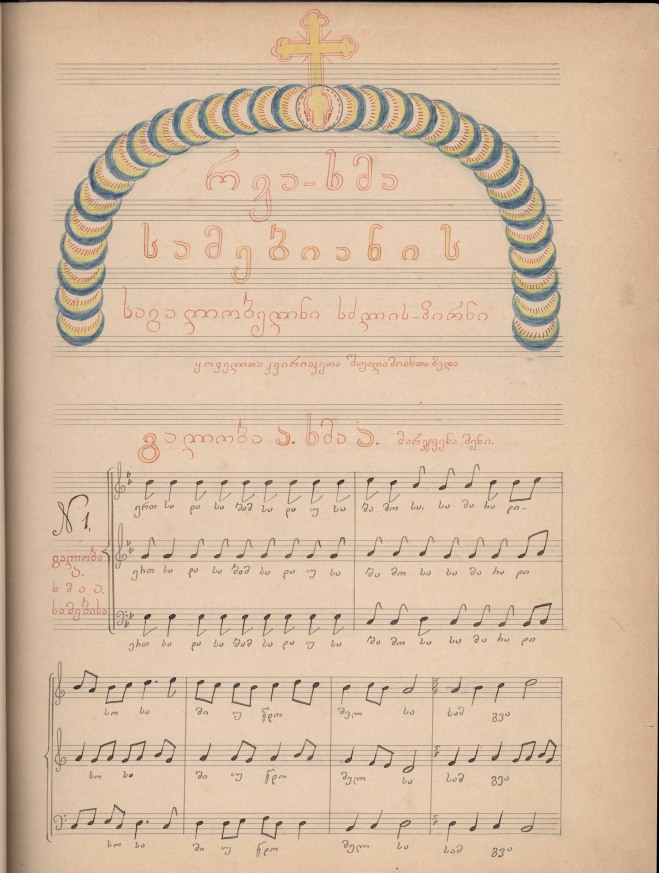

Front page of sheet music collection of the liturgy published by Maxime Sharadze and _Amkhanagoba_ printing house, which was transferred to notes by Filimon Koridze. 1895

In the following years, more collections of chants recorded in Imereti were published. Estate Kereselidze greatly supported Maksime Sharadze, and together with their like-minded companions, another important step was taken to preserve Georgian chants for future generations.

Estate Kereselidze

In 1893, Filimon Koridze was sent to Ozurgeti, where he was to record the Gelati School chants from the old singer Anton Dumbadze, his son Deacon David, and Svimon Molarishvili.

Anton and David Dumbadze

To begin with, Anton Dumbadze did not believe that it was possible to record these chants, but he later made a determined effort to record them. In "Iveria" he wrote: "As a high-ranking professional of Georgian church chanting, I enjoy the fact that these chants are transcribed into musical notes, unchanged and flawlessly faithful to the original tone which existed and exists in Guria-Imereti."

Filimon feared that this national treasure would be lost forever. In the early 1900s, he traveled to Ozurgeti for the second time. Although the number of recorded chants was growing, there was not enough money to print them all. Maksime Sharadze was waiting for the right time, but sadly he passed away in 1908. The business of the printing house and the recording of chants went into decline.

Filimon Koridze and his team.1890. The second row from the right is Estate Kereselidze

Then in 1911, Filimon Koridze himself died unexpectedly at Bakhmaro resort and was buried in Ozurgeti. No archive documents or recordings were found in the apartment he had rented. Filimon's son recalled his father’s words, "I entrust the sheet music to a very reliable person, very reliable... You will learn about him later!" It appeared that Estate Kereselidze, a member of Maksime Sharadze's brotherhood, was a perfect example of someone completely committed to his profession right up until the end of his life. Estate (later known as Ekvtime Confessor) was entrusted with the task of transcribing the recorded chants, and Filimon made the corrections. Upon returning to Tbilisi, Filimon’s son inquired as to the whereabouts of Estate Kereselidze, and was informed that the latter had moved to a monastery and become a monk.

_Kereselidze.jpg)

Monk Ekvtime (Estate) Kereselidze

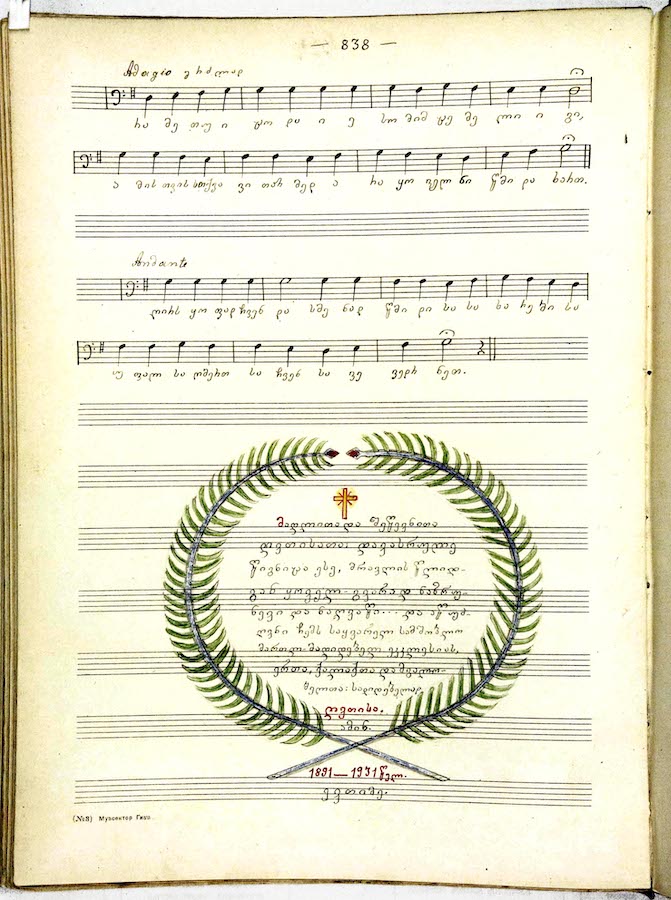

Ekvtime (Estate) Kereselidze had been ordained as a monk, and was then working at Gelati Monastery, devoting all his time to copying chants. His contribution is a turning point in the history of recording Georgian chants as sheet music. It is remarkable how much love, care, and effort he invested in transcribing and compiling these collections, embellishing them with the finest traditions of old Georgian handwriting and beautiful calligraphy. The National Center of Manuscripts is home to over thirty of these collections, each of which ranges in size from 300 to 1000 pages. Ekvtime Kereselidze safeguarded 5,532 musical notation sheets of various chants.

The sheet music collection of Bishop Stepane (Vasili) Karbelashvili, which contains over 2,000 chants, is also preserved at the National Center of Manuscripts. While Filimon Koridze was in charge of recording chants in Western Georgia, Deacon Grigol Karbelashvili, who was the foremost expert on tones in Eastern Georgia, led the process in that region. His five children - Peter, Andrew, Stepane, Polyeuktos and Filimon - are canonized saints. The chants of the Chanting School of Svetitskhovli, which were transcribed into musical tones by the Karbelashvili brothers, are still called "Karbelas" tones.

Holy Karbelashvili brothers. From the left: Holy Confessor Polyeuktos, Holy Confessor Stephen, Holy Martyrs Peter and Andrew

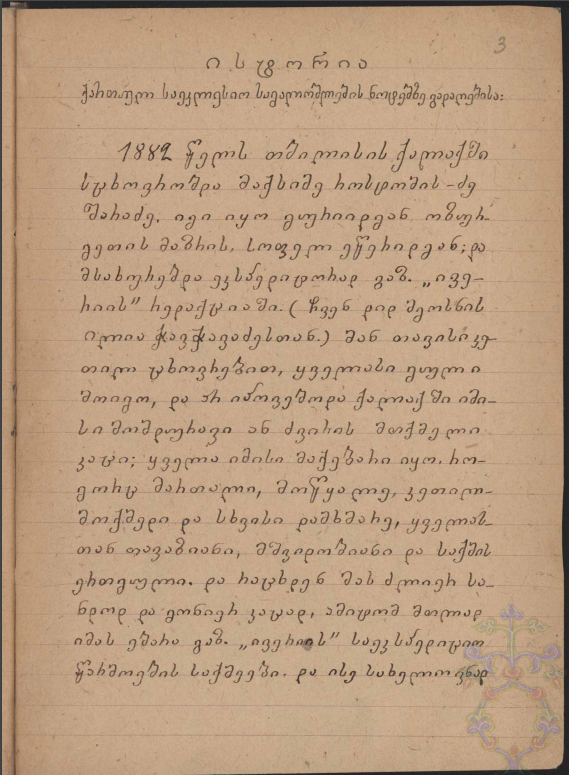

Alongside the chant manuscripts, Ekvtime Kereselidze also wrote the "History of Recording Georgian Church Chants on Music Sheets." The narrative included on the 120 pages of a small notebook that is now housed in the National Center of Manuscripts also serves as the autobiography of Ekvtime the Confessor. He dedicated his entire life to his beloved pursuit.

Estate Kereselidze. The History of Recording and Printing Georgian Chants as Sheet Music. Front page of manuscript Q-840 preserved at the National Manuscript Center

Filimon Koridze's concerns were not groundless: "I am most afraid that, after my death, all this treasure will become a trap for mice somewhere in a cellar or in a museum." And indeed, a very difficult and dangerous path lay ahead for the chants that had been transcribed into note form.

After Maksime Sharadze passed away, the co-owner of the printing house divided the collections of chants into two parts, and donated them to the Museum of the Historical and Ethnographic Society. Ekvtime requested them from the Society, and rewrote them once more. He then moved to Kutaisi, where he took his own share of the printing house. The printing house business in Kutaisi was unsuccessful from the very outset. He could not find a place to store the collections of chants. Many of the sheets were destroyed because they were not stored in adequate conditions. Later, Ekvtime came across a very unpleasant incident – butchers were wrapping pieces of meat in the manuscripts.

With the assistance of priest Razden Khundadze and the regent of the Kutaisi Cathedral choir, Ivliane Nikoladze, Saint Ekvtime wrote the chants that had been recorded in Guria in all three voices. Ekvtime requested these manuscripts several times, rewrote them, and compiled collections of chants. He worked tirelessly at Gelati Monastery, surprising those around him with his dedication. "I discover immense wealth, a priceless treasure in this work that is more valuable than gold, silver, or pearls!" Ekvtime used to say.

A fragment of a Georgian church chants transcribed by Ekvtime Kereselidze. Preserved in the National Center for Manuscripts

In 1924, the Communist terror increased in Georgia, and the Georgian Church suffered many hardships. The Catholicos-Patriarch of Georgia, Saint Ambrosi (Khelaia) was arrested after he had sent a letter to the Genoa Conference informing the world of Russia's subjugation of Georgia. The majority of high priests were behind bars, and Gelati Monastery was closed.

It was necessary to move the manuscripts from Gelati to a secure place. It is quite astounding how strong a person can be at such a time, yet Ekvtime Kereselidze put the collections of chants that were stored in iron boxes onto a cart, and easily transported them to Mtskheta along the highway regularly raided by Red terrorists. He then moved into the Patriarchal Cathedral of Svetitskhovli together with the treasure he had saved.

A fragment of a Georgian church chants transcribed by Ekvtime Kereselidze. Preserved in the National Center for Manuscripts

On August 18, 2003, the Church of Georgia canonized Ekvtime Kereselidze and named him St. Ekvtime the Confessor. His merits are comparable with those of the Georgian scientist and patriot Ekvtime Takaishvili, who spent 24 years in exile in France and restored to his homeland the national treasures that had been taken during the February 1921 occupation, in such a way that "he did not lose a single pin."

A fragment of a Georgian church chants transcribed by Ekvtime Kereselidze. Preserved in the National Center for Manuscripts

Back in his homeland, in the grounds of Zedazeni Monastery, Ekvtime Kereselidze secretly buried the collections of unique Georgian chants that over the years he, Filimon Koridze, and their associates had recorded, transcribed, and preserved. Two decades later, Ekvtime Kereselidze transferred these collections to the State Museum in order to safeguard them for future generations.