Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Edmond Kalandadze (ედმონდ კალანდაძე) was born on May 4, 1923, in Guria, a strikingly beautiful region of Georgia, Monde in childhood, baptized by a priest under the name of Gabriel. Over the course of time, the childhood impressions and experiences that Edmond had acquired in the village of Khidistavi garnered different echoes and intonations and were transformed into various colors on canvas, drawing viewers into the master’s delightful world.

Edmond Kalandadze. 50x70. Oil on canvas. 1992. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Edmond Kalandadze. A breeze on the bread field. 41х33. Canvas, oil 2010. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Edmond Kalandadze. Shadow Street. 60Х52. Carton, oil. 1993. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

The 1950s was an important and interesting period of change in both the outlook and artistic language of Georgian culture and fine arts. It was at this time that Soviet art witnessed the birth of new, initially vaguely defined art movements, which began developing in parallel with the already well-established Socialist Realism.

Edmond Kalandadze. End of the day by Panthean. 60x50. Canvas, oil. 2008. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Edmond Kalandadze. Canvas, oil. 50х60. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Edmond Kalandadze was one of the forerunners of these new art trends in Georgia. Mastering the techniques of Pompeian frescoes, and Renaissance and European painting, greatly contributed to the formation of the young artist’s pictorial language. Kalandadze expressed his opposition to the propagandistic role of Soviet ideology and art as early as his period of studies at the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts. Naturally, his relationship with the Academy’s officials turned adversarial, and was to remain so for years to come. Edmond’s diploma works, “A Portrait of the Singer Tatiana Makharadze” and “Harvesting,” were subjected to severe criticism by the Academy. The artist tried to find a new form of depiction within the official ambit of Socialist Realism by lightning his palette and applying more free, loose brush strokes to the canvas. This attempt did not go unnoticed by the sharp eyes of the Soviet censors, and the young artist was left without a diploma.

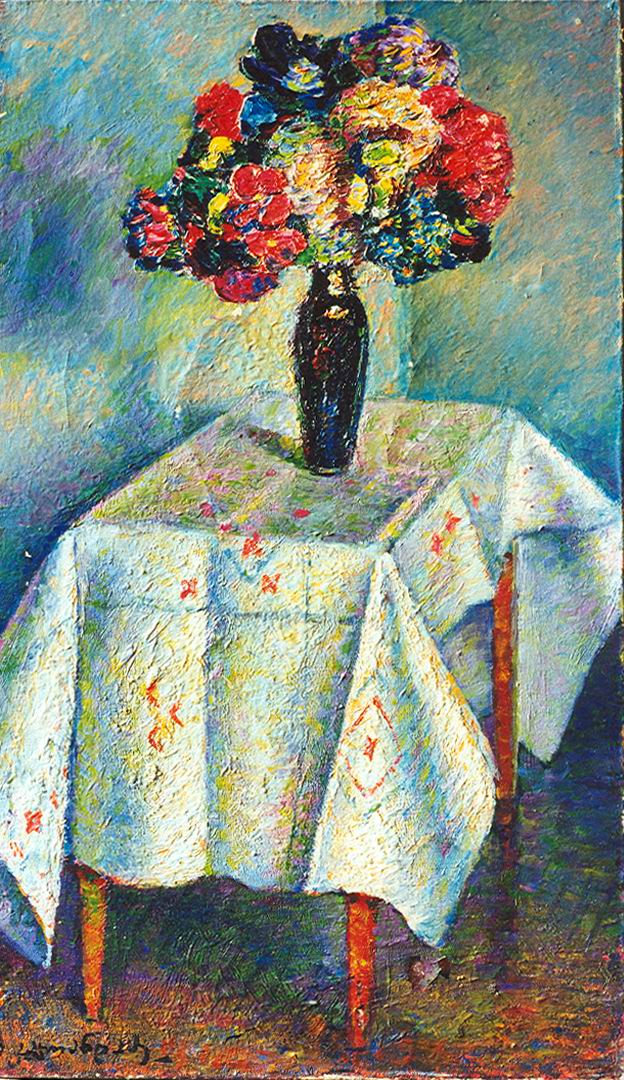

Still Life with Artificial Flowers. 50x85. Canvas, oil. 1956

In 1955, at an exhibition organized at the Tbilisi Art Gallery, the artist presented several of his works: "Grandmother’s Portrait," "A Still Life," "Zurab Nizharadze’s Portrait," "Eter Andronikashvili’s Portrait," and "The Vorontsov Bridge." In the exhibition space, these pieces clearly stood out for the particular sonority of their colors. "This is an event," is how the art critic and artist Rene Schmerling expressed his impression of Edmond’s artwork.

Two years later, Moscow hosted the First World Festival of Youth and Students. This event, together with the Picasso exhibition that had been held in Moscow a year earlier, marked the beginning of the end for the ideological “iron curtain.” The festival exhibited Edmond Kalandadze’s painting “Z. Nizharadze’s Portrait.” Kalandadze became a laureate of the competition, and finally obtained a diploma from the Art Academy.

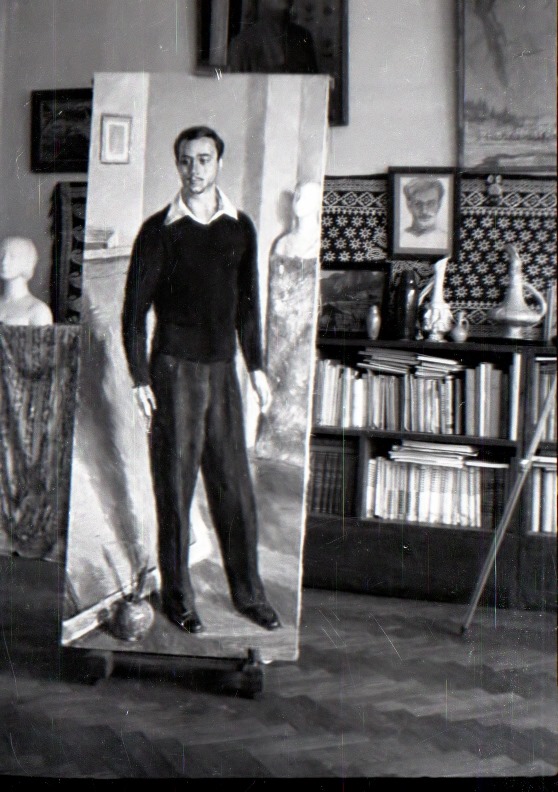

Portrait of Zurab Nizharadze. 1950s. National Museum of Georgia.

Portrait of Piso. 70x49. Canvas, oil. 1955. Artist’s Studio

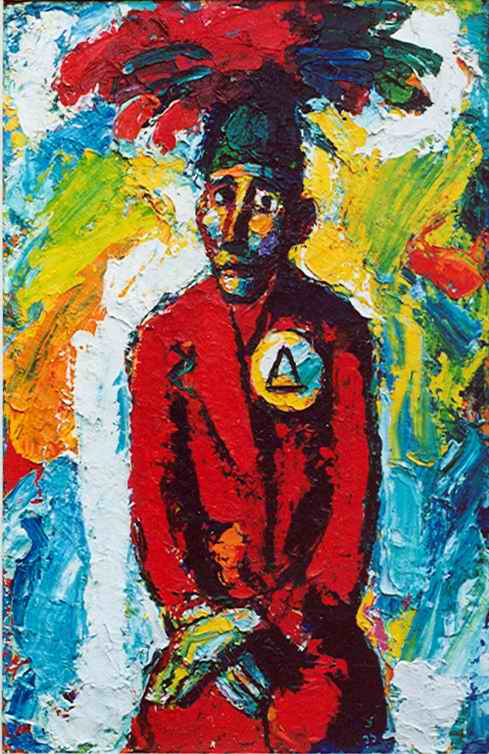

Fictitious General. 100x65. Cardboard, oil. 1987. Artist’s Studio

Edmond Kalandadze’s art is based on the artistic embodiment of nature and human passions. The uniqueness of Kalandadze’s artistic language derives from his own perception and comprehension of the world, and of the coexistence of nature and man - the world and the individual. Reality, the most complex substance that is rife with either harmonious beginnings or contradictions of existence, is one of the defining foundations of Kalandadze’s work. Each of Edmond’s paintings is a kind of microcosm created and revealed to us by the artist. Kalandadze’s perception of the world, its interpretation and understanding, are revealed through an unusually interesting and individual artistic method. Painting is a powerful tool of communication that the artist employs in order to interact with the environment. Kalandadze’s oeuvre transforms today’s world of contradictions into various artistic images and themes: landscapes, portraits or still lives (“Still Life With a White Milk Jug,” Buffaloes in the Alazani Swamp,” “Once, a Long Time Ago,” “Boats,” “Bathers”). While based on the order of the elements of artistic language, Edmond’s paintings still contain certain features of a “game.” His works almost always create an impression of improvisation and artistic joy.

Edmund Kalandadze. Two Oaks. 41x47. Oil on canvas. 2007. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Edmond Kalandadze. Sartichala 44X54. Canvas, oil. 2002. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

When painting any theme, Edmond Kalandadze tries to grapple with the most challenging problem - finding his place and destination in the world where he perceives himself. Kalandadze’s active and dynamic nature is manifested through his artistic images. He takes on the role of neither storyteller nor distant spectator. Edmond’s landscapes are mostly "portraits" of nature depicted as a living creature, with its own mood and spirituality. Kalandadze’s perception of the world and understanding of its “text” undergo visible changes throughout the artist's creative journey. The "impressionist" landscapes with their shimmering colors give way to images of a turbulent nature that possess an inner drama, where the line between the real and the imaginary is blurred. His landscapes emphasize the spontaneous origins of nature. Nature always dominates man, and man eventually fuses with nature (“A Garden,” “Wind,” “A Wheatfield,” “The Rain Has Passed,” “Elevated Mtkvari”).

Edmond Kalandadze. PIanes 60x50. Canvas, oil. 2003. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Edmund Kalandadze. Oda In Woods. 49x54. Oil on canvas. 2003. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

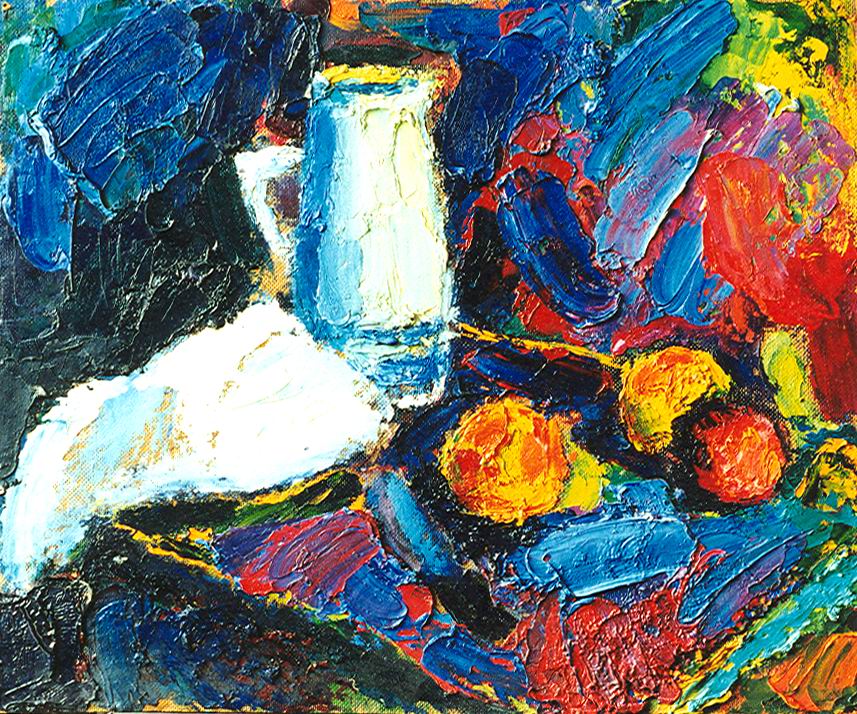

Still Life with White Milk Pot. 50x60. Cardboard, oil. 1959

In the 1980s, the artist’s oeuvre saw a proliferation of thematic compositions. In the works of that time, the subtext so characteristic of Kalandadze’s paintings “resurfaced,” and came to explicitly embody the artist’s personal experiences and his perception of reality. Kalandadze's adherence to moral principles is manifested in his assessment of contemporary social and political events. The artist found compromises to be unacceptable, both in the formal language of art and in terms of understanding existence. Regardless of its motive, violence begets violence, and is unacceptable in civilized society. In the 1980s, Kalandadze’s works clearly proclaimed humanist ideas that were seriously challenged in the 20th century. The value of each human life, the importance of man and nature, and the right to a harmonious coexistence serves as the ideological credo of Kalandadze’s oeuvre. The themes conveyed in Edmond’s works "Refugees," "My Sisters, Unforgettable," "Crucifixion," "Execution in Didube," and "Robbers" are extremely intense and convincing in terms of their artistic and moral impact. The artist depicts scenes of violence and aggression as a reflection not only of a local, but of a universal problem.

Edmond Kalandadze. Oil on canvas. 80x60. 1990. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Nude. 66X80. Canvas, oil. 2005. Private collection

For Edmond Kalandadze, existence is a manifestation of life and death, love and violence, harmony and disharmony, chaos and order. The artist employs “visual forces” such as shape and color to express these powerful elements. Kalandadze writes: “For an artist, art is a way of fighting transience. It’s a daring dream to be a creator and to create a world of your own, where you and only you will be the judge and governor of everything; where you can feed on your own imagination, build towers of justice and forgiveness, take upon yourself the right to punish and forgive, and, at the same time, to have a clear understanding that this is a game, and, as the wise Thomas Mann would say: ‘this is a game, but a serious game’.”