Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

The village of Dmanisi lies some 85 kilometers south-west of the Georgian capital, Tbilisi. In the Middle Ages, Dmanisi was one of the most prominent cities and an important stop on the Silk Road. The area has therefore long intrigued archaeologists, who have been excavating the crumbling ruins of a medieval citadel there since the 1930s.

Dmanisi Nakalakari (the ruined town of Dmanisi) constitutes a significant record of Georgian history. In the Middle Ages, Dmanisi was one of the most powerful political, economic, and cultural centers in Georgia. The remains of splendid churches, defensive structures, and agricultural buildings from this era have been preserved even to the present day.

View of Dmanisi

Historical photos of excavations and scientists

Dmanisi has been the site of excavation works for several decades. These were carried out at various points by the renowned Georgian scientists Levan Muskhelishvili, Vakhtang Japaridze, and Jumber Kopaliani. In 1983, the eminent Georgian paleontologist Prof. Abesalom Vekua identified the tooth of a now-extinct rhinoceros, which along with other fossils found in the same year, allowed him to determine the geological age of these layers – the early Pleistocene, or more than one million years old. In the following year, the first stone tools were also discovered. In 1984, it also became clear that the remains of early human life were buried under the medieval buildings at Dmanisi. A new era of Dmanisi research began in 1991, following the discovery of a

Hominid Lower Jaw

The age of the Dmanisi layers was determined through the integration of several different methods. Volcanic rocks were dated at the Berkeley Geochronology Center in California using the so-called potassium-argon method. The established absolute age is 1 million 850 thousand years. Paleomagnetic studies of Dmanisi sediments revealed that the remains were fossilized during the so-called

Dmanisi Rocks

Dmanisi Rocks

.jpg)

From left: Leo Gabunia, Abesalom Vekua, Davit Lortkipanidze, 2000

Five hominid skulls were found here, enabling the reconstruction of a portrait of a inid from that time – a hominid that differed from us in terms of cranial anatomy. There was a much smaller brain volume, no forehead, the jaw was larger, the teeth were different, and the shoulders were primitive, while the lower limbs were similar to ours – that is, inids at that time were already able to run quite long distances. The Dmanisi skulls belonged to individuals of different ages. One was a teenager, one was younger, two were adults, and one was elderly without a single tooth left in its mouth. These remains are well-preserved, and thus allow very detailed analysis.

The minids of Dmanisi were about 145-162 cm tall, weighed between 40-50 kilos, and their brain volume was 546-730 cm3 (that of a contemporary human is about 1300 cm3).

There is an ongoing dispute among scientists about the taxonomy of the Dmanisi hominids. Some scientists classify them as Homo erectus, yet according to others the peculiarities of the indicators permit the possibility of separating them into a new species – Homo georgicus.

Hominid Skulls

Hominid Skulls

In addition to traditional morphometric and morphological research, study of the Dmanisi skulls was also conducted using computer techniques. As a result of tomographic scanning, the missing parts of the face were reconstructed by means of a computer. On the basis of these data, the French sculptor Élisabeth Daynès and American paleoartist John Gurche produced their artistic reconstructions.

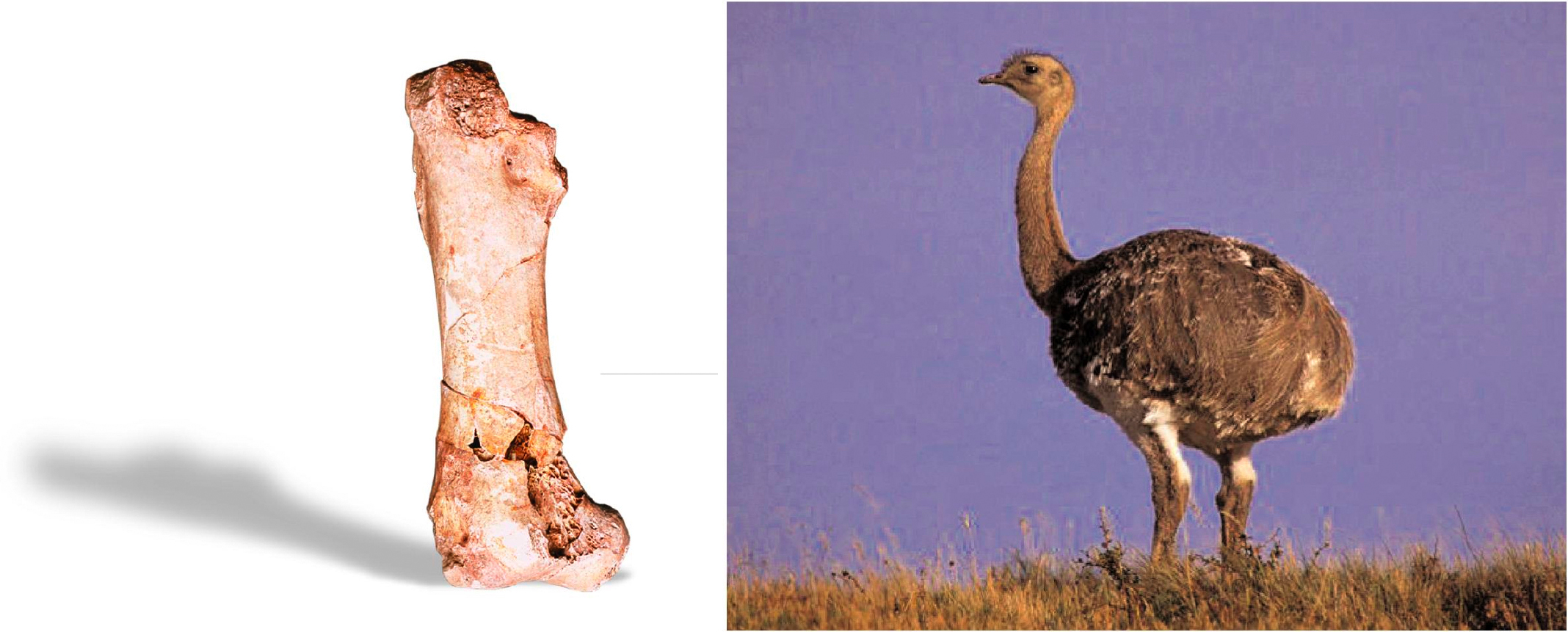

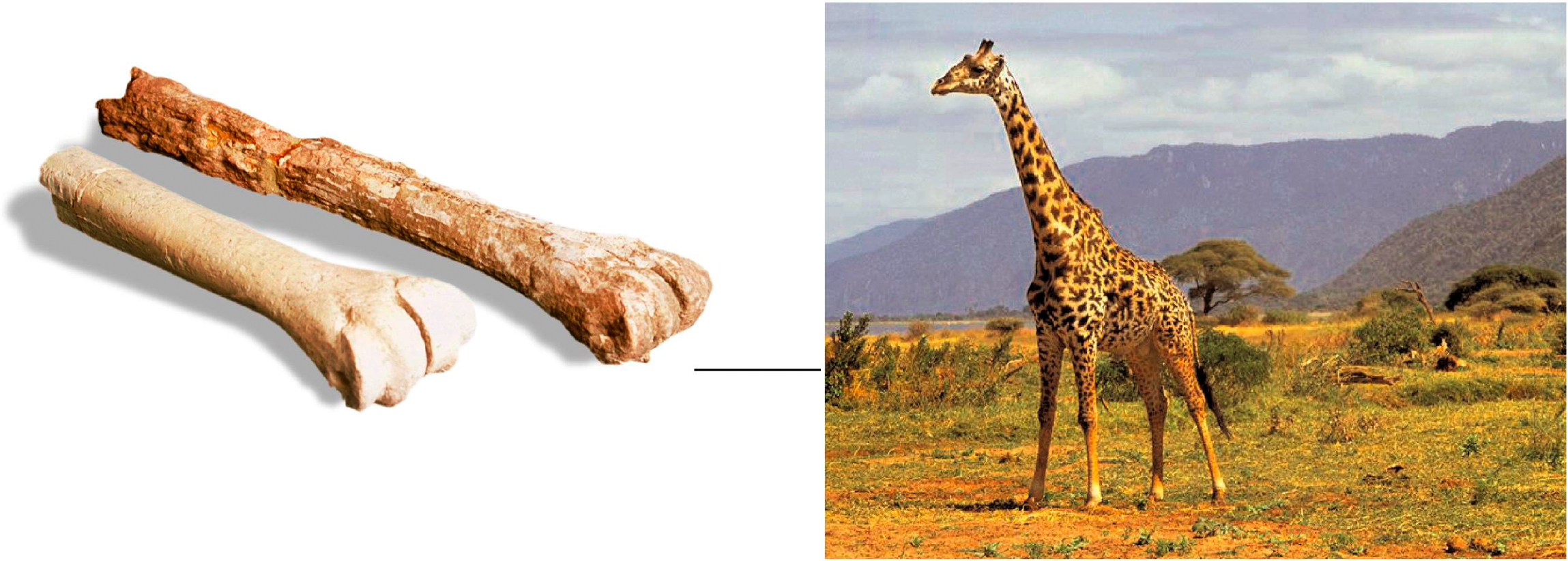

The vertebrate fauna found at Dmanisi reflects the diversity of the natural conditions at that time. This is also confirmed by paleobotanical data. To date, more than 10,000 bones belonging to at least 50 different animal species have been identified. Bones excavated at Dmanisi prove that saber-toothed tigers, hyena, giraffe, rhinoceros, elephants, ostrich, deer, and other animals lived here. These groups had become extinct in the region by about 1.5-2 million years ago.

Animal Bones

Animal Bones

At the time of the early hominid settlement of the Dmanisi area, there was also a diverse landscape. Savanna type vegetation was replaced by areas of forest. A climate similar to that of the modern Mediterranean region prevailed. It seems that the location of these hominids was near a lake. The local environment represented a biotope that was rich in plant and animal resources, as well as raw materials for producing stone tools.

The stone tool-making skills of Dmanisi hominids. The collection of Dmanisi is quite rich. To date, more than 5,000 stone tools have been unearthed. In the Dmanisi complex, stone flakes significantly outnumber

Tools discovered

Unfortunately, we have not been able to find any direct data regarding the presence of Dmanisi hominids. They probably engaged in foraging and hunting small animals, and fed upon the flesh of large predators. In addition to this, we have made a very important discovery in the form of a hominid skull. This skull and its jaw belonged to a sick individual; moreover this particular individual lived toothless for several seasons. The specimen found at Dmanisi demonstrates a distinctly human trait: the ability to care for others and show compassion.

Nowadays, scientists agree that the hominid remains discovered at Dmanisi have significantly altered previously existing theories. Research led by Georgian scientists has confirmed that the remains found here are the earliest and most primitive in Eurasia. Nowhere else in the world have so many remains from this era been found at a single location. The Dmanisi discoveries have invalidated the previously existing opinion, that the migration of hominids from Africa was connected with technological progress: that only after the assimilation of eule techniques did the first migration of early man from Africa take place. The Dmanisi data confirms that the movement of hominids occurred much earlier by anatomically more primitive hominid groups.

Dmanisi preserves a complex archaeological record of numerous reoccupations, which are registered in both stratigraphic and spatial concentrations of artifacts and faunal remains across all areas of the site. Up to date, almost 5,000 stone tools have been found. While flakes comprise the majority of tools recovered, some cores and ppes have also been found. The raw material for the lithic artifacts came from nearby rivers. The difference in technology is not only observed through changes in the composition of assemblages. Before the Dmanisi finds, experts believed that humans could not have left Africa before having developed advanced technology such as the Acheulean, in which tools were symmetrically shaped, manufactured, and standardized. The tools found at Dmanisi, however, are simple flakes and choppers according to much the same primitive Oldowan tradition that hominids in Africa were practicing nearly a million years earlier.

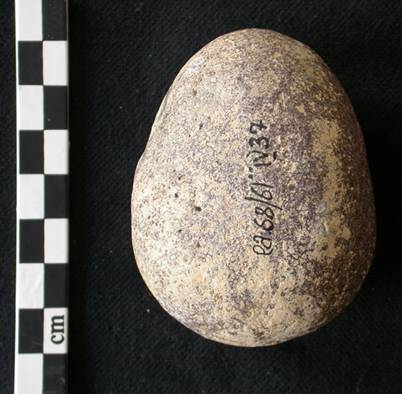

The Dmanisi discoveries have gained wide recognition throughout the world. According to Science, one of the world's most authoritative scientific journals, the Dmanisi discoveries were ranked third among the 10 most important events in world science in 2000, and in 2013, the fifth hominid skull was named as the best fossil of the year. From the 1.77-million-year-old rhinoceros tooth discovered at Dmanisi in 2019, researchers were able to extract important genetic information - an almost complete proteome protein sequence. This is a breakthrough in ancient biomolecular research, allowing scientists to reconstruct an evolutionary picture for much earlier eras than had previously been known. This provides fresh opportunities for studies in both animal and human evolutionary histories. Research at Dmanisi continues... In 2021, the National Geographic Society included Dmanisi in their publication “100 Discoveries that Changed the World.”