Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Sergo Kobuladze (სერგო კობულაძე) began working on the curtain for the Tbilisi Opera and Ballet State Theater in around 1954-1956. The creation of the curtain in the theater space has always been of special importance. For the audience, the curtain is exceptional, festive, and magnificent. The curtain is not associated with any particular performance. It forms both a real and a visual-conditional boundary of the artistic world. It is most appropriate to consider such a curtain in the context of synthesis of the arts since while being an example of monumental painting corresponding to architecture, it is often also influenced by theatrical and decorative elements.

The artist drew various sketches and outlines for the Tbilisi Opera House curtain (curtain: 120 m2, Harlequin: 36 m2) spending over five years on the project. Several versions of the curtain were drawn up. According to available documentary material, a compositional illustration based on the theme of Zakaria Paliashvili's opera Absalom and Eteri was placed on the curtain during the first stage. The remaining space was devoted to a portion of an enormous, bulky and rather rigid carpet-patterned curtain. The artist later changed his mind and replaced the narrative compositional element with the image of a mythical character. The audience dubbed this portrait the "Muse of Music." The artist himself referred to it as Orpheus but added that the figure, which physically resembles a woman with Hermes wings on its feet, a laurel wreath on its head, and a lyre in its hand, could, and actually did come to represent the Parnassus residents as a whole. The degree of generalization increased, while the specificity to the narrative proportion decreased. Music, as a form of common cultural thought, was more fully embodied in this image.

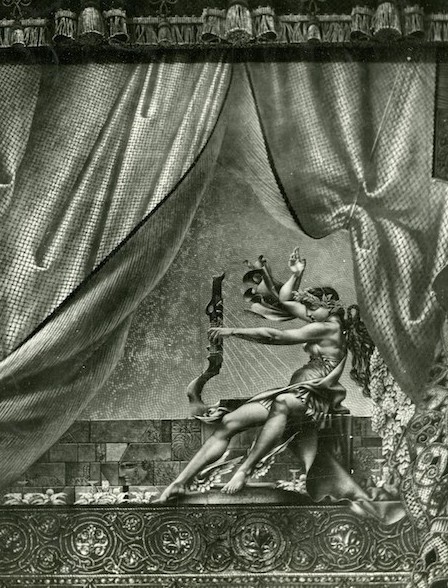

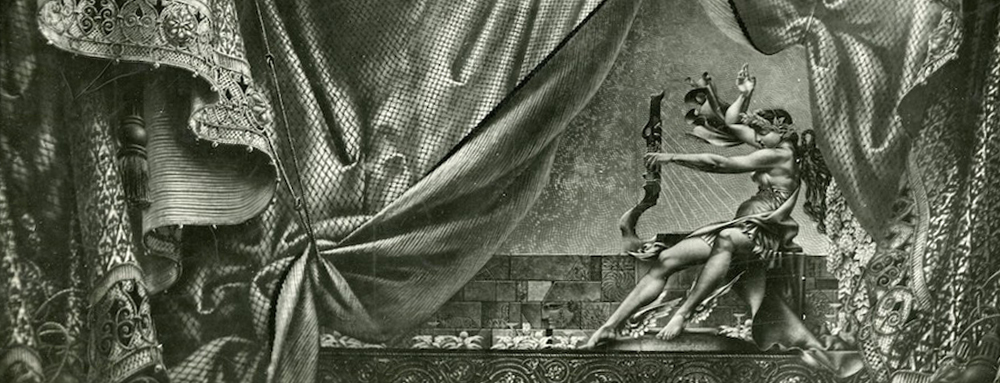

Sergo Kobuladze. Curtain sketch. 41,7x59,5. 1954-1959

Viewed from today's perspective, Sergo Kobuladze's creative work raises many questions. Even a relatively shallow analysis of the artistic heritage available to us is enough to reveal the fallacy and insufficiency of applying unambiguously linear evaluation criteria to the work of many artists from that era. Artistic analyses appropriate to the context, historical-political circumstances, and common cultural tendencies make clear that it would be incorrect to only attribute the creator's interest in producing realistic shapes to the requirements of the epoch.

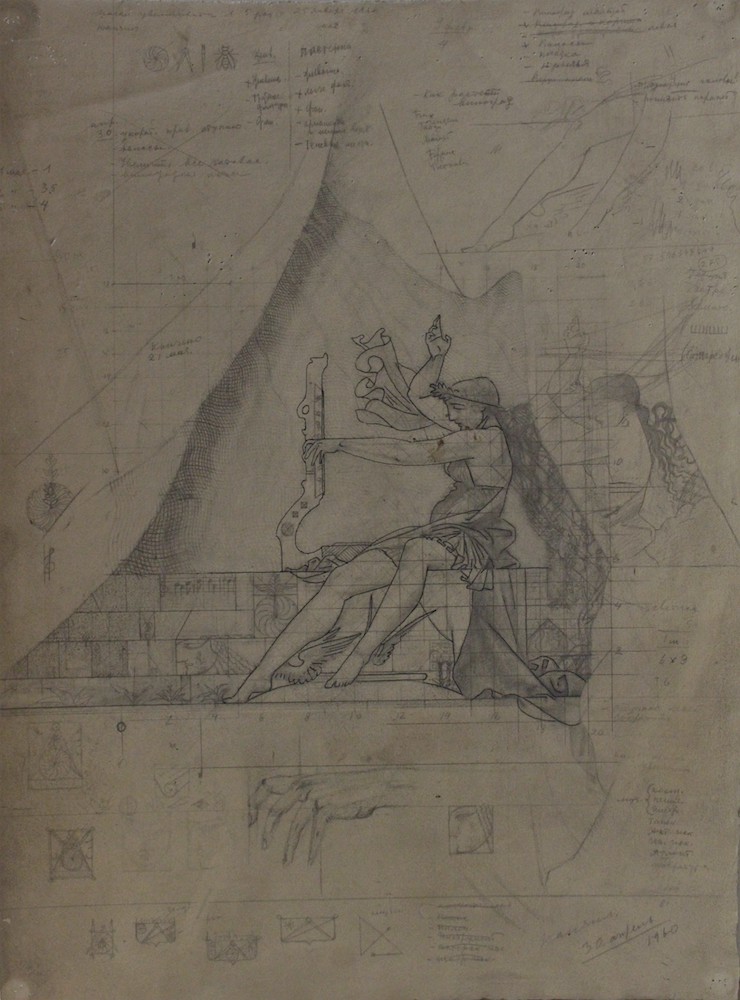

Sergo Kobuladze. Curtain sketch. 95x120. 1958-1961

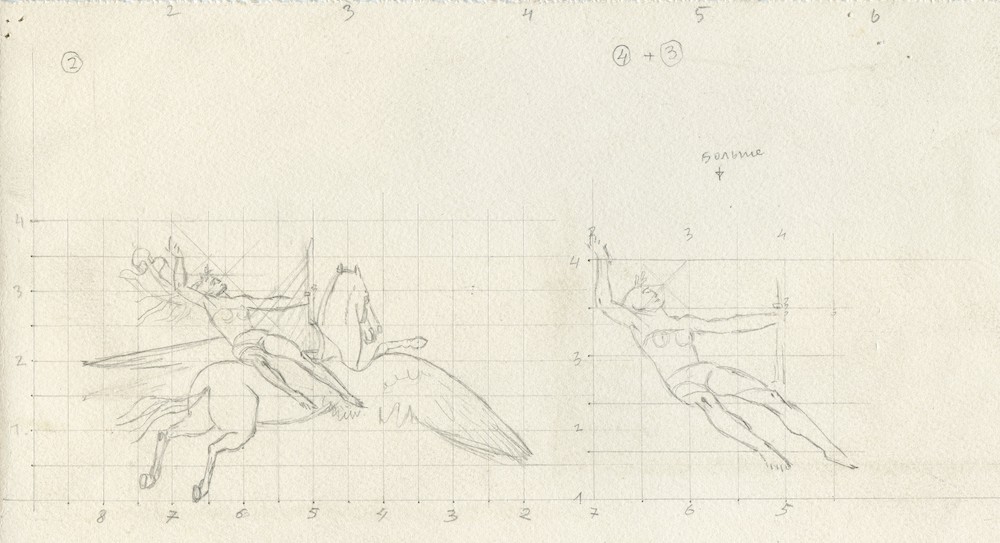

Tactile-dense, full, and wholly corporeal material – this is Kobuladze's interpretation of form. The artist’s maximalist character is revealed through his continual and almost interminable process of perpetual performance-perfection of paintings. Before reaching his final decision, he would make a series of sketches, preparation works, and innumerable rough drafts. Such is Kobuladze's painting in general. That is how he worked on the curtain intended for the Opera House. But in none of these preliminary drafts or sketches does the intensity of emotion slow down even a little; on the contrary, it strengthens, becomes more intense, and in the final versionis more flexible and tense. Kobuladze rejected he momentary spontaneity of creation based solely on emotions, which is why his creative pursuits are so diverse. He considered all possible versions, constructed, placed the figure in different poses and situations, and rearranged the composition every time, and to an infinite amount. Although the artist always opted for the most condensed, almost non-alternative version of the picture in terms of compositional-structural and formal interpretation, the final versions of the artist's works (the ones intended for viewers) demonstrate this. The artist employed the "multi-layer painting" technique to produce the opera curtain, taking into consideration the expertise of earlier masters. “This information has been lost. Since I was young, I have been attempting to study and solve it, but despite utilizing certain nuances while working on The Knight in the Panther's Skin (S. Kobuladze), I couldn’t finalize it. ” Here he is referring to the multi-layered painting method used by Italian painters of the Renaissance. The technique was based on the optical fusion-mixing of colored layers and required precise color and shape calculations on the part of the artist. Based on this approach, a spatial-volumetric image with almost stereo characteristics was produced. In addition, the only determinants of the higher-colored levels were all of the lower-colored layers. Since the image was based on visual "formulae", the necessity for main tainting the correct distance between the artist and the image surface (the artist walking on a huge canvas spread out on the floor would be 3-4 meters away from the surface of the image if he climbed a ladder) no longer presented an issue. While working on the curtain, possible dangers and difficulties arising from the frequent movement of the curtain (the constant raising and lowering of the curtain during performances; deformation of the fabric resulting from bearing its own weight in astatic hanging position) were also taken into consideration.

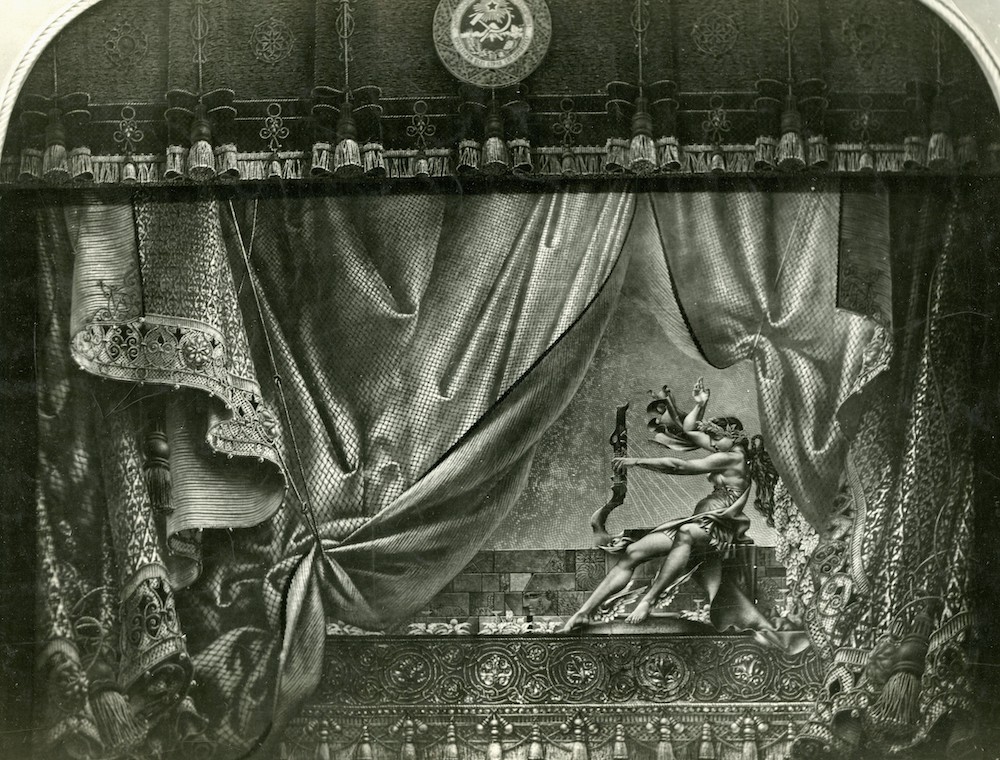

Sergo Kobuladze. Main Curtain. 1960

The work was completed in 1961, and in order to celebrate such an important event the Opera Theater presented it to an audience. The audience was thrilled, but the political elite still identified certain flaws. Their comments focused on the allegorical figure depicted on the curtain –the very part of the work where the artist's unique traits were most visibly displayed. The flat profile of the figure proclaimed free artistic thought in the meticulously natural environment. The conventionality brought about by such a contrast did not fully conform with Soviet social realism, or to be more precise, it provided a reason to question the latter’s linearity. On the other hand, by its essence the theater seemed to forma basis for justifying such conventionality. The curtain’s opening night was thus met with ambivalence, although it was universally recognized that Sergo Kobuladze had bestowed upon Georgian society a work of outstanding value – not only in terms of his own creative output, but also the whole history of Georgian art in the twentieth century.

In 1973, Sergo Kobuladze's pictorial curtain was burned in a fire that broke out in the Opera House. The decision was immediately taken to restore it. It is notable that at this time the curtain evolved into one of the symbols of the Tbilisi Opera House. The artist made a completely new sketch for the restored version. The painted curtain portion remained unchanged, while the compositional detail was replaced with a new narrative element – a winged steed with an allegorical figure of a muse upon it.

Sergo Kobuladze. Curtain sketch. 1975

However, this idea was not implemented. It was clear that the work required the same strength, spirit, and vigor that had once given Kobuladze the faith in overcoming the impossible. However, aside from his physical abilities, there was another and perhaps more important decisive factor: as a creator, Kobuladze was no longer interested in producing a similar work, let alone replicating it. The solution appeared fifteen years ago, and as it turned out for the artist, finally. That is how Sergo Kobuladze's most prominent work disappeared and the story ended, becoming a part of history for all time.