Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Iranian easel painting from the 18th and 19th centuries occupies an important place in the history of both Iranian and global art. Owing to the fact that its initial creation and subsequent development occurred precisely during the reign of the Qajar dynasty in Iran, it is frequently referred to as Qajar or Royal Persian Painting. One of the world’s largest collections of easel paintings from the Qajar era is housed at the Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, which is a part of the National Museum of Georgia.

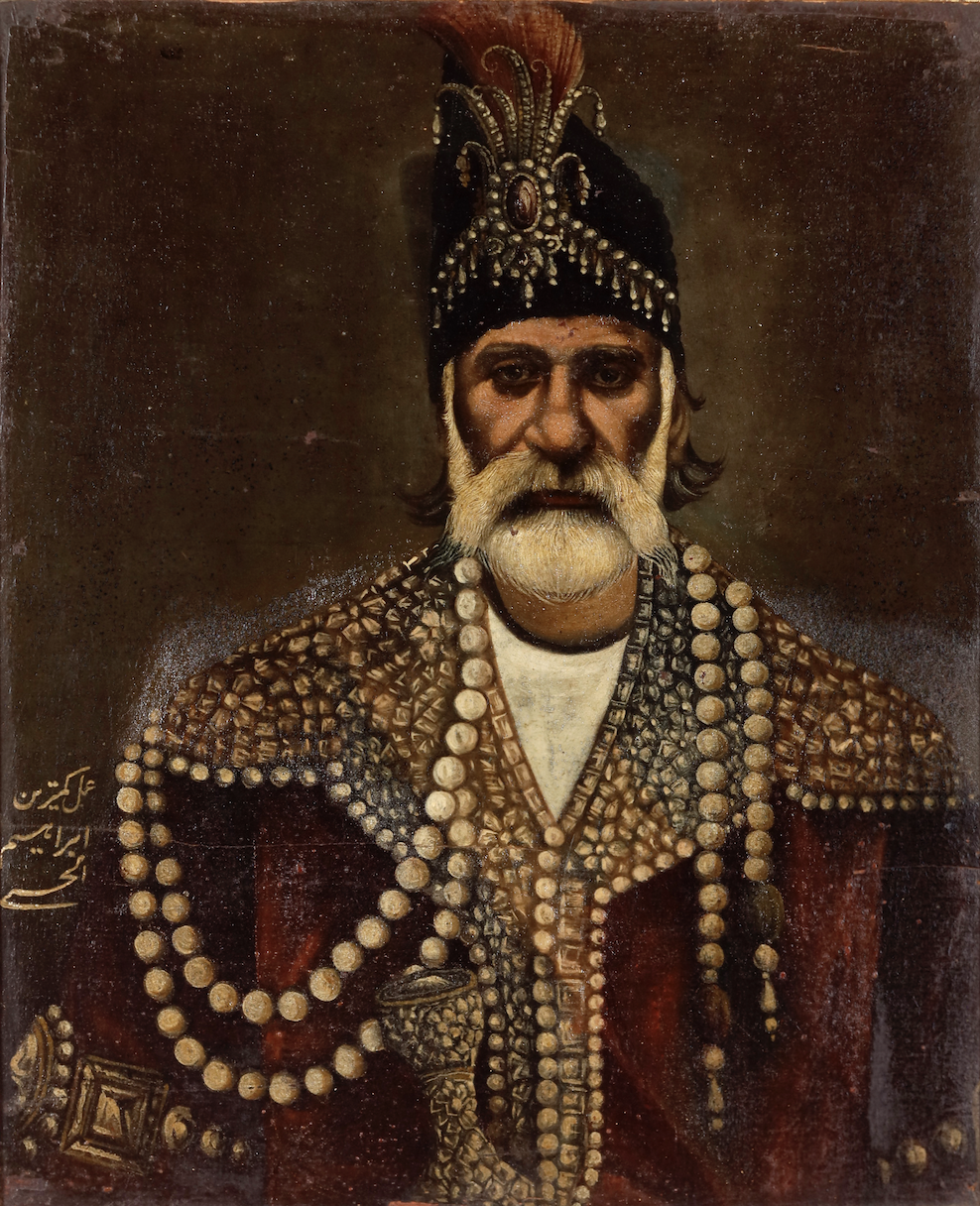

Iran's Qajar dynasty rose to prominence around the end of the 18th century. Its founder, Agha Mohammad Khan (1789-1797), mercilessly attacked the rulers of Iran at that time, the Zand dynasty, and subsequently externalized and strengthened the kingdom. His successor, Fath-Ali Shah (1797-1834), inherited a throne that was in dire straits: the Russian, British, and French Empires, with which the kingdom was constantly involved in diplomatic and physical conflict, remained adversaries in Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asia. This rivalry was labeled the "Great Game," and in the political history of the nineteenth century is referred to by that name. Notwithstanding the kingdom’s terrible political circumstances, lost battles and lost territories, Fath-Ali Shah’s name is associated with the emergence of the country's cultural life. By virtue of the development of a wholly original visual style, Fath-Ali Shah was able to send specific ideological messages to both the allies and enemies of his kingdom. One of the most important messages was the close connection between dynasties and their continuity. Fath-Ali Shah renovated the palaces that had been constructed by previous monarchs, and erected portraits of their forebears on the contemporary monuments, since the Qajars were believed to be the descendants of the historical or mythological Iranian monarchs (the Qayanids, and Safavids).

During his rule, Iranian art underwent a dramatic transformation. . Throughout the new secular structures, the walls were lavishly adorned with murals and colorful, poetic paintings on canvas artworks. Through the fusion of European painting techniques with Oriental vision and style, they created entirely unique, vibrant canvases brimming with life and grace. Many years later, this novel aesthetic was referred to in academic literature as Qajar art.

The art of the Zand Dynasty (1779-794) exerted an immense influence on the formation of this style, despite the political controversy. The artistic language of the Zand era - its remarkable delicacy and sophistication of forms, the abundance of details and colorful textures, lyrical and erotic scenes, and its particular intimacy - was successfully mastered by the Qajar school, although the style is distinguished by a more subtle linear decoration, and monumentalism.

During the reign of Fath-Ali Shah, several themes and narratives often recur in Qajar painting. One is an official portrait of Fath-Ali Shah, while the other is a group portrait, in which the Shah greets us along with a large number of male and female court musicians and dancers.

Each phase of the evolution of the Qajar painting school is represented in the Iranian painting collection housed at Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts . This fact particularly highlights the significance of this collection.

As previously noted, the Qajars' rise to power in Iran was accompanied by a shift in the worldview and philosophy of the ruling class, which subsequently influenced painting aesthetics and standards of beauty: a new ideal of beauty was established that differed greatly from previous ones.

The museum houses two beautiful portraits from the 18th and 19th centuries: portraits of the young Abbas Mirza and a portrait of the legendary hero of Firdausi’s Shah Name, Fereydun. We notice the half-tone modeling of his face, which is typical of Zand painting, as well as the typical ceremonial attire of Qajar art: brilliantly colored clothes (the red garment of Fereydun), and certain accessories. The portrait of Fereydun is signed by the artist Haji Agha Jan.

Portrait of Abbas-Mirza, Unknown artist. Iran. First part of 19th cent. Oil on canvas, 81x60 cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv.N. 857

Portrait of Feridoun. Artist Haji Aga Jan. Iran. First part of 19th cent. Oil on canvas, 75x72 cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv.N. 2088

The picture "Reception at the Shah's Court", which is the size of an easel painting, signs are evident that reveal its proximity to the pro-European style of painting - creating the composition on a balcony, and the inclusion of a European figure in the illustration. Although the picture is closer to miniature art, dualism can still be perceived: the coexistence of two types of –vision – miniature and easel painting principles – can easily be observed.

Audience at the Court of Shah. Unknown artist. Iran. First part of 19th cent. Oil on canvas, 105x70 cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv.N.110

The canvases Musician and Woman with Deer reveal even more proximity to the principles of easel painting, where depth is perceived through the slight turning of the figure and the receding background: the principles of perspective that are characteristic of European art were emerging. Nevertheless, the soft, voluminous forms that appeared as a result of European influence are combined with Iranian art's striving for decorativeness – the meticulous depiction of clothing details and accessories.

Musician. Unknown artist. Iran. First part of 19th cent. Oil on canvas, 85,5x71 cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv.N.860

Woman with a Deer. Unknown artist. Iran. First part of 19th cent. Oil on canvas, 140x83,5 cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv.N.853

The portraits of dancers, musicians and Iranian beauties that are preserved in the museum (Woman with a Mirror, Woman with a Ewer, Dancer with Castanets, and Dancer with a Drum are the best examples of early Qajar art. They are exquisite, bright, decorative and highly colorful. "Sisters", "Woman with a Parrot", and "Boy with a Hawk" share the artistic style of the same period. These canvases have more decorativeness, dominance of the linear forms; they are clear, impressive, colorful, and are characterized by a remarkably refined vision built upon tonal gradations of red, blue and gold.

Woman with a Mirror. Circle of Muhammad Hassan. Iran. First part of 19th cent. Oil on canvas, 107x76 cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv.N. 92

Woman with a Ewer (Golabdan). Circle of Muhammad Hassan. Iran. First part of 19th cent. Oil on canvas, 107 x 76 cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv.N. 925

Dancer with Castanets. Unknown artist. Iran. First part of 19th cent. Oil on canvas, 155x 87 cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv.N 858

Dancer with a Tambourine. Unknown artist. Iran. First part of 19th cent. Oil on canvas, 155x87 cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv.N 859

Sisters. Unknown artist. Iran. First part of 19th cent. Oil on canvas, 117x72 cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv.N 854

Woman with a Parrot. Unknown artist. Iran. First part of 19th cent. Oil on canvas, 162x 85,5 cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv.N 924

Youth with a Falcon. Unknown artist. Iran. Fath-Ali Shah period (1798-1834). Oil on canvas, 158 x 80cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv. N 914.

Following the ascension of Fath-Ali Shah's grandson Mohammad Shah (1834-1848) to the throne of Iran, certain transformations in the formal style of Qajar art were observed. Although the Qajar style of this period retained its basic motifs and indications, new narratives arose, the technique changed, and the pictures became less ceremonial. The painting style acquired the characteristics of easel art, which led to alterations in the compositional structure and modeling of the form. The collection includes five works illustrating this period, each reflecting a different stage in the evolution of Qajar painting style. The "Portrait of Mohammad Shah" stands out among them.

Portrait of Muhammad Shah. Unknown artist. Iran. Muhammad Shah period (1834-1848). Oil on canvas. 209,5x104cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv. N 116

The Shah is portrayed clothed in a traditional Qajar ceremonial gown, and wearing royal jewels that his great-grandfather, Fath-Ali Shah, had selected precisely for the coronation event. This painting is of particular interest, because in the dozens of portraits and miniatures painted of him, he is always depicted wearing a European outfit. "Woman with Tambourine" is a kind of continuation of the theme of dancers and musicians that had been popular during the reign of Fath-Ali Shah. While the woman is dressed in traditional Fath-Ali Shah attire, the picture is more reminiscent of the "Shirin Master's" circle of the Mohammad Shah era owing to the type of figure and the more loosely-drawn pictorial style.

A Woman with a Tambourine. “Shirin Painter.” Iran. Muhammad Shah period (1834-1848). Oil on canvas. 100x82 sm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv. N 856

Dancer is also distinctive. The composition of the picture is still traditionally presented, with the full-length body against the background of the balcony, but we also notice a change - the woman is portrayed wearing a crinoline dress. The color palette of the painting is also different. The predominant pigments are red and green; the strong, vivid hues that lent the artworks of the preceding century their distinct decorativeness are no longer present. In addition, the style of execution is different: the forms are inscribed more coarsely, graphically, and flatly.

A Dancer. Unknown artist. Iran. Muhammad Shah period (1834-1848). Oil on canvas. 162,5x102cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv. N 923

Portraits of lovers reappear in art from the Mohammad Shah period (1832-1848). There are two similar canvases in the museum’s collection, both of which portray full-length figures - lovers with servants. Both images are identical in composition and execution style, and must be the work of one artist. In style, they are close to the art of the Fath-Ali Shah circle, and were most likely produced early in the reign of Mohammad Shah. These canvases are the finest representations from this time, featuring high standards of professionalism and exquisite taste.

Lovers with a Servant. Unknown artist. Iran. Muhammad Shah period (1834-1848). Oil on canvas.150x90cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv. N 917

Lovers with a Servant. Unknown artist. Iran. Muhammad Shah period (1834-1848). Oil on canvas.150x90cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv. N 917

Naser al-Din Shah (1848–1896) became the ruler of Iran in 1848. Throughout his reign, much attention was paid to the advancement of art, which acquired new elements. With the founding of the classical art academy in Tehran in 1850, European easel painting techniques became even more evident in the works of Iranian artists. While large-scale, ceremonial-style works still existed, miniature art and lacquer paintings were developing at the same time. Iranian clothing was also evolving: men's and women's overcoat, which are a traditional garment for both sexes, were becoming more popular, elaborately embroidered with "boteh" patterns. The canvas "Layla and Majnun" which is preserved in the collection somehow continues the theme of the previous era, but at the same time the characters are dressed differently – the image assumes more of an easel-like and chamber-like appearance, while the attempt to depict voluminous forms and space is heightened.

Layla and Majnun. Unknown artist. Nasir al-Din Shah period (1848-1896). Iran. Oil on canvas. 95x67cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv. N 115

There are two paintings by Abul Qasim Isfahani. Notwithstanding the size of these easel pictures, both of the artworks display the color palette and decorativeness typical of miniature and lacquer painting. The artist mostly worked using these media, and his lacquer paintings - decorative chests, pencil cases, picture frames, and tables - are the only other examples of his work that have survived. These two easel paintings, on the other hand, are even more valuable because they reveal the artist in a quite different light.

Spring. Artist – Abul Kasim Isfahani. (1902). Iran. Oil on canvas. 83x60,5cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv. N 931

Portrait of the Unknown Noble Man. Unknown artist. Iran. The end of 19th c. Oil on canvas. 150x90cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv. N 109

Two more original paintings, Portrait of a Nobleman and Muzaffaruddin Mirza's portrait must have been created at the end of the century. Husein's Portrait of a Nobleman exhibits distinctive traits of European painting, including the use of light, the modeling of form, and the expression of distinct characteristics and emotions. In the same manner, the future Shah Muzaffaruddin is portrayed sitting in a chair at the age of 14. Gentle halftones have been meticulously employed to depict the boy's face. His gloomy eyes are fixed on the viewer. The picture has an inscription on it that identifies Hasan, the royal court painter, as the artist, and also mentions the years 1862–1863.

It is important to note that two paintings kept in the collection, Woman with Child and Man in Black, reveal obvious stylistic contrasts, and are credited to the Georgian-Iranian school. Even though their compositions are somewhat reminiscent of the early Qajar painting style, these portraits stand out for their volumetric modeling of figures and simple, restrained color palette. Interestingly, they bear a striking resemblance to Georgian easel paintings from the 18th and 19th centuries.

Portrait of the Unknown Noble Man. Unknown artist. Iran. The end of 19th c. Oil on canvas. 150x90cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv. N 109

Muzafarad-Din Mirza Portrait. Artist Husein. Iran. (1967-68). Oil on canvas. 60x49cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv. N 2095

Georgia's access to such extensive and varied Iranian collections was clearly influenced by relations between the two nations. Hundreds of Georgians worked in Iran, and played an important role in the country's political and cultural life. Simultaneously, the oriental style began to permeate Georgian daily life predominantly as a result of Iranian influence. Such close historical ties have resulted in this remarkable collection of artworks, some of which were bestowed on Georgia as gifts, and some of which the Georgian people themselves collected and preserved as testament to the centuries-long relations enjoyed between these two countries.

A Man in Black. Unknown Artist. Georgian-Persian school. The edge 18th -19th cc. Oil on canvas. 179x83,5cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv. N928.

A Woman with a Child. Unknown Artist. Georgian-Persian school. The edge 18th -19th cc. Oil on canvas. 179x83,5cm. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Fine Arts, Georgian National Museum. Inv. N927