Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

From the 1880s to 1910, a new stage began in Georgia’s fine arts development, propelled by professionally educated artists of the older generation that "gave birth" to modern Georgian secular painting. It was a move that partially broke the link with the Tiflis feudal, oriental, and portraiture painting school, which ceased to exist in 1880. Naive, dilettante and secular painters with a feudal-oriental background were replaced by painters who had mastered in Europe and Russia. The Georgian artists of the time understood realism in their own way, and did not seek immature assimilation with European classical and Russian Peredvizhniks (representatives of critical realism). Russian critical realism, with Narodnik roots, was an intruding phenomenon connected to the political circumstances of the time, towards which we do not find much empathy among the artists of the older generation. When deciding between national and social tendencies, representatives of Georgian critical realism chose national, which, with a critical awareness of realism, took roots in art bearing ethnographic-documentary accuracy and value.

Georgian critical realism included subtexts on the stabilization of the national program, which was conditioned by the lyricism and ethnographic specificity of the genres. By veiling socialism, the Georgian artists expressed their desire for freedom and resistance to their "interventionist" neighbor. Foreign professionals joining the Caucasus Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts at the end of the 19th century, played a significant role in forming the professional artistic space. Russians perceived strengthening national painting in the Caucasus as an unfavorable condition and a threat. Foreign artists received more recognition than Georgian artists did- the lack of promotion and realization largely coming from the country's economic problems. Non-Georgian citizens, particularly Armenians and Azerbaijanis, represented Georgia's big bourgeois class. Therefore, European, Russian, and Armenian artists received the most attention in Tiflis' artistic community.

The first Georgian professional artist was Grigol Maisuradze, although he was never exhibited, and hence his works are unfamiliar to the broader public. The first personal exhibition of a Georgian artist, Gigo Gabashvili, was held in 1891. In 1895, Gabashvili was again exhibited, this time in a group exhibition, alongside G. Bashinjaghiani, L. Zankovsky, A. Shamshimian and other foreign artists. From the 1860s to the 1890s, the works of foreign and Georgian artists of different styles were intensively featured in shows in Tiflis, among them I. Aivazovsky, V. Vereshchagin, G. Bashinjaghiani, A. Shamshimian, H. Hrinevski, A. Eisner, and G. Gabashvili. Inclusion of a Georgian artist's name among the aforementioned artists reflects both the cosmopolitan context of Tiflis and the economic challenges encountered by Georgians following the collapse of feudalism. The plethora of professional artists, whose representatives will be discussed below, were mainly educated in Russia (Petersburg, Moscow) and Europe (Munich, Paris).

Gigo Gabashvili. Alaverdi. Oil, canvas mounted on cardboard. 33x44. 1883. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

A Short Journey through Georgian Realistic Painting - Artists of the Older Generation (1880-1910)

It is impossible to comprehend Georgian critical-realist painting without spotlighting artists Romanoz Gvelesiani, Davit Guramishvili, Aleksandre Mrevlishvili, Gigo Gabashvili, and Gigo Zaziashvili. Several works of each artist, and a diachronic review, can clearly define the realism in Georgian art, as well as the authentic line, which included a national-ethnographic grounding in which the Peredvizhniks’ painting, European realism and academicism were stratified.

Romanoz Gvelesiani (1859-1884) participated in the Caucasus Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts, and attended the St. Petersburg Imperial Academy of Arts. Due to his early demise, he was unable to further his studies in Italy as he wanted. The artist primarily painted landscapes of the capital city and his native region, Kakheti, as well as portraits and etudes of real-life scenes. Gvelesiani, like the other artists mentioned above, created several sketches and etudes in a mythological, symbolic style. Nude, erotic, mythological and religious citations clearly demonstrate the creator's search for himself through European artistic processes. However, in this case, we should discuss the artist's realistic painting and his contribution to the evolution of Georgian realism.

Gvelesiani's graphic work ‘A Young Lady’ gives the feeling of being unfinished. The work depicts a Georgian lady in national clothes and headgear, whose contemplative facial expression is achieved by skillful shading and lighting. The drape of her clothing, national headwear, and feelings of intimacy are all conditional. The rough strokes of Indian ink, countless details, achromaticity and lighting, with white spots on the dress, highlight the woman's mood and feelings. In addition to the refined animalism, the work displays a portrait of a realistic spirit, as opposed to the lyrical-romantic style that was popular in the portraits of the preceding Tiflis School.

Romanoz Gvelesiani. A Young Lady. Paper, pencil, Indian ink. 16x25. 1880

Romanoz Gvelesiani also created the picture ‘Kakhetian Peasant with a Jug’, in which a Kakhetian peasant's national and deeply meditative appearance is shown in a chamber setting. The entourage is dominated by a light gray background, an internal stairway, and a carpeted bed, the colors of which emphasize the national charge. A half-lying peasant, exhausted and contemplative, drinks away his sorrows. The ethnographic-documentary narrative of the canvas highlights the realistic mood - rug, jug, peasant clothes, tobacco pipe, and the poor chamber background stylized with folk ornaments, and allow us to inquire about the Georgian peasant's life, clothes, and other informative details. ‘At the Avlabari Bridge’ depicts Tiflis city life and architecture in an ethnographic-documentary manner. Conditionality, realism and incompleteness are symbiotically linked through air composition and architectural perspective. The city's eclectic architectural landscape is further enriched with symbolically drawn images of people engaged in trade and communication processes.

Romanoz Gvelesiani. Kakhetian Peasant with a Jug. Canvas, oil. 31.5x29. 1883

Romanoz Gvelesiani. At the Avlabari Bridge. Paper, pencil. 32x39.5. 1880

Alexander Mrevlishvili's (1866-1933) work, like Romanoz Gvelesiani's, is multi-layered. Symbolism, academicism, and critical realism were the styles in which Mrevlishvili attempted to find ipseity. His paintings include nudes, citations of religious-historical themes, and portraits. The artist first obtained an academic education at a religious seminary in Moscow, and later continued his studies in Paris under such teachers as Longo and Polenov.

Nearly all Georgian realist painters of the time sought to find themselves through aesthetically irreversible or incompatible trends.

From the realistic works of Alexander Mrevlishvili, ‘Portrait of Mother (Natalia Abuladze-Mrevlishvili)’ is worth noting. The graphic portrait is created with an intense feeling of reality. It is safe to equate this work with the "hyperrealistic" or "photogenic" realism of the 19th century. Exquisite formalism and the artistic approach show the translation of the daguerreotype into a graphic image. The noble facial expression, national headdress, twisted braids, fabric filigree, and standing are rendered not artistically, but by replicating the 19th-century daguerreotype, demonstrating the artist's mastery.

Alexander Mrevlishvili. Portrait of Mother – Natalia Abuladze-Mrevlishvili. Paper, pencil. 59,5x50,5.

Davit Guramishvili's work ‘Oriental City Corner’ displays a popular eastern life scenario typified by critical realism. Critical realism viewed socialism not only from a national, but also from a cosmopolitan and global perspective. The spread of the concept of socialism weakened the politics of the national program, which is why Georgian artists such as the "Tergdaleulebi" (those educated in Russia) created art that strengthened the ideas of national consolidation. Yet, the issue of Orientalism in Georgian realism cannot be ignored. The meticulousness of the narration in Guramishvili's capturing of the oriental space is expressed by the clothes, minarets, pointed barrel vaults, and togas sewn from colorful fabric. The low social or working class can be spotted in the clothes of the mother, baby, man, and in the people's activities. In the topicality of the painting of Asia Minor, we can see evidence that Georgian artists working in critical realism were "forced" by the ideological program of Russian art to show sympathy and solidarity towards the lower classes of all countries.

Davit Guramishvili. Oriental City Corner. Oil on canvas. 46x32. 1912

Gigo Gabashvili (1862-1936) represents critical realism. Gabashvili's graphic and pictorial works are primarily divided into two: realism and symbolism. In Tiflis, he trained under Keppen and Franz Roubaud, both of whom worked mainly in military art. Gabashvili continued his studies in St. Petersburg, and later went to the Munich Academy of Fine Arts. Having been “poisoned” by Repin in St. Petersburg, and admired by the Peredvizhniks, Gabashvili encountered German, Swiss, and French Symbolist artists in Munich. From Munich, he wrote that adapting to the European artistic space and its processes was “challenging.” The Peredvizhniks’ painting and ideas, as well as those of Repin, remained significant to him. It is difficult to comprehend Gabashvili’s subjective position from the letters he wrote to his friend. Perhaps owing to Russian political pressure, he was accustomed to thinking this way, and sought to avoid the spontaneous force of symbolism, which later entirely overshadowed his modest admiration for Repin.

In this context, we will highlight the artist's realistic works depicting Central Asia, battle scenes, different parts of Georgia, and portraits of both Georgian and non-Georgian citizens, as well as the creative aspects of national ethnographic values.

We can categorize Gabashvili’s realistic portraits into two groups: Those of public figures, which are ceremonial and demonstrative, and those depicting Georgians or individuals of different nationalities from the lower class.

‘General Amilakhvari’ is a realistic reinterpretation of a ceremonial portrait. The General is presented against a conditional chamber background, portrayed full-faced, with a keen, somewhat skeptical gaze. The brown background, composed of maroon, gray, ochre, black, and dark tones, creates a sonorous yet harmoniously monolithic color palette by contrasting achromatic and chromatic colors. A mirror-like or smooth surface distinctly indicates the regular application of oil paint strokes. The draping of the clothing folds, the military epaulets and insignia, and the sword in its scabbard, are executed with extreme realism, the feeling of which is further strengthened by the old man's skeptical expression.

Gigo Gabashvili. General Amilakhvari. Canvas, oil. 124x110

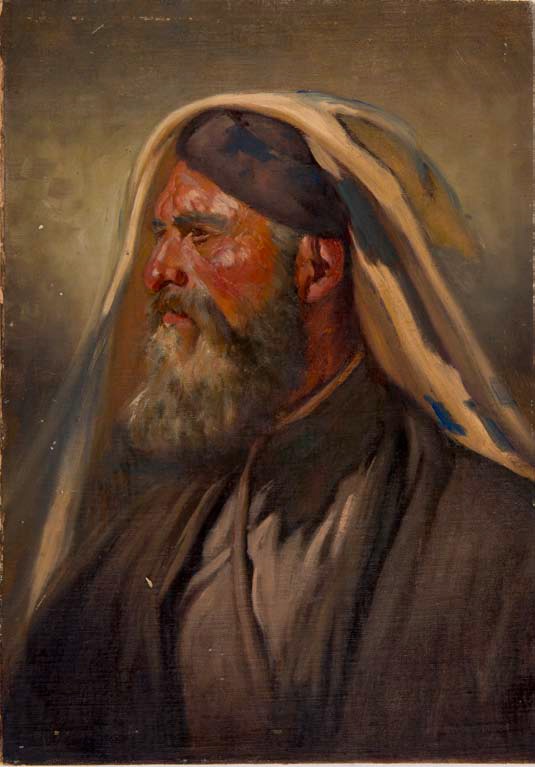

Among the numerous portraits of non-Georgian individuals from the lower class, ‘Man in a Turban’ stands out as particularly noteworthy. The facial features and expression are conditional; the turban, clothes and background are executed with intense, rough strokes. Visually perceptive, the strokes of contrasting colors seem less localized and tend to follow an up-down direction. The portrait of the ‘Kakhetian Peasant’ is painted in profile, and the facial features and expression are less conditional, conveying a penetrating, reflective gaze. The folds of the clothes are depicted in greater detail and the brushstrokes are regular and flowing. Both portraits are valuable in terms of national-ethnographic correctness and documentalism, while the importance of “Peredvizhnik socialism" and "cosmopolitan sympathy" for the lower classes is highlighted. It is impossible not to recognize Gabashvili's Georgian or Central Asian landscapes as falling within a national-ethnographic perspective.

Gigo Gabashvili. Man in a Turban. Canvas, oil. 1894

Gigo Gabashvili. Kakhetian Peasant. Canvas, oil. 40x27

The Khevsureti series, and images showing ‘Svetitskhoveli’, reflect the national spirit. Natural heritage and cultural heritage are raised to the ideological layer of nationality, which is expanded by scientifically studied life and a realistic fixation on the peculiarities and traditions of Georgian nature, without any embellishment. Similar principles are used to create scenes of Central Asia, particularly in the painting the ‘Samarkand Market’, where the artist presents scenes of commerce, everyday life, architecture, and clothing from a distance; observing them objectively rather than subjectively, on the verge of ethnographic informativeness and realism. Expressive language, meticulousness, and the dissonance of colors modified by light, unite into a somewhat carpet-like decorative whole.

Gigo Gabashvili. Landscape of Mtskheta. Oil, canvas mounted on cardboard. 40x53,5. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Gigo Gabashvili. Svetitskhoveli. Canvas, oil. 66x54

Gigo Gabashvili. Samarkand Market. Canvas, oil. 113x100

Gigo Zaziashvili (1868–1952) is recognized for his realistic portraits. He painted the portraits of numerous Georgian writers and prominent figures. Having no formal education, he began by painting signboards with Niko Pirosmanashvili, but quit due to a lack of orders. Even though Zaziashvili was an amateur artist, he was more attracted by Gigo Gabashvili's realistic style than Naive painting. It was Gabashvili who organized a solo exhibition for Zaziashvili. He also created caricatures for multiple publications, and was actively involved in acquiring exhibits for the National Gallery.

‘Portrait of Ilia Chavchavadze’ and ‘Dervish’ are very different portraits. They strongly reflect the school, ideology and vision of the aforementioned artists.

Gigo Zaziashvili. Ilia Chavchavadze. Cardboard, oil. 71,5x53. 1937

Gigo Zaziashvili. Dervish. Canvas, oil. 115x62. 1905

The portraits of national heroes and people of non-Georgian origin help us comprehend critical realism in terms of the appropriateness of national (Georgian) and sociopolitical (Russian) programs,

The artists of the older generation played a pivotal role in the history of Georgian fine art by introducing realistic and professional painting traditions.