Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

There are numerous statues by the sculptor Merab Berdzenishvili (1929–2016), both in Georgia and outside of it. Each of them, when considered separately, exhibits different aspects of the sculptor's individual handwriting, represents all of the indications of the time and era, and reveals the multitude of artistic trends, innovations, and changes that existed in the Georgian artistic space of the 20th century.

Merab Berdzenishvili first appeared in Georgia’s artistic circles in the late 1950s. One of his final works dates to the beginning of the 21st century. This period, both within and outside the country, bore witness to numerous developments in the historical-political and socio-cultural spheres. There were also major transformations, such as the fight against the personality cult, the Khrushchev Thaw, the establishment and acknowledgment of later rejected socialist realism, the search for something new, post-Soviet postmodernism, and so on. These processes posed significant challenges to the development of Berdzenishvili's creative-expressive language, as it did to many other representatives of his generation.

The sculptor, born in one of Tbilisi's oldest districts, was sent to the village by his parents for a time during World War Two, together with his brother, Elguja, who is also a renowned Georgian artist. At the time, it was easier to earn a living in the countryside than in the city. Merab Berdzenishvili saw a forge for the first time, while in the village; metal, its structure, qualities, and potential - metal as an element, a material, a tool, and finally as art – thereafter became the central focus of his life.

Merab Berdzenishvili. Medea. 1967-70. Bronze. Artist's studio

Merab Berdzenishvili. Medea. 1967-70. Bronze. Bichvinta

When working on voluminous forms, he discovered that bronze was the most fitting and striking material to use. The propaganda-ideological thread of epochal, colossal sculpture must also be taken into account. Monumental sculptures came as direct requests and orders from the state, while bronze was the most in-demand and popular material during the Soviet dictatorship. Sculpting such statues in stone would have been more difficult and, in most cases, technically impossible. This is not to say, however, that Berdzenishvili did not carve stone sculptures (Autumn, 1978; Nude, 1969; Michelangelo, 1976).

When working in stone, the artist entirely obeys and follows the flow of the material, inspired by its texture, structure, and volume, as if attempting to let the stone dictate the form, and not to interfere excessively in this process. Berdzenishvili retained the integrity of his perception of this multicolored mass, and even made it the primary expressive approach of the work. That is why his stone carvings are relatively small in size and, despite their striking monumentality, are distinguished by an extraordinary intimacy (Boy with Chuniri, 1960; Portrait of a Mountain Dweller, 1971). When he sculpted in bronze, he removed and eliminated all barriers with the hardness, static, and inflexibility of the metal (Medea, 1970; They Will Grow Even More, 1975; Soldier's Father, 1978; statue of Zakaria Paliashvili, 1972; Me, Grandmother, Iliko, and Ilarion, 1986).

Merab Berdzenishvili. Nodar Dumbadze memorial. 1986. Bronze. Tbilisi

In 1955, Merab Berdzenishvili began designing his diploma work - a statue of Shota Rustaveli. This piece presented a distinctly different portrayal of the poet in the Georgian reality, as, rather than focusing solely on his physical appearance, Berdzenishvili chose to emphasize Rustaveli's emotional characteristics, offering a new interpretation that set his sculpture apart from previous representations.

Merab Berdzenishvili. Shota Rustaveli. 1956. Bronze. Tbilisi

Merab Berdzenishvili. Shota Rustaveli. 1956. Bronze. Tbilisi

Berdzenishvili's Rustaveli is distinguished by an athletic build, unlimited self-restraint, and an unveiled respect. This portrayal encompasses a variety of contrasting elements. The statue features a forward movement of the head and shoulders, coupled with a backward step. In terms of content, it represents an enamored poet who understands that true love involves relinquishing personal desires; he is a thinker whose peers are few in the annals of history; a man, who, humble and lonely, remains forever separated from his homeland. To reveal the essence of the character, the sculptor contrasts will and emotion, as well as a strong emotional conflict. The first small prototype of this statue can be found at one of the entrances to the National Library in Tbilisi. Berdzenishvili returned to the theme of Rustaveli several times throughout his career, culminating in a highly stylized interpretation of the poet, which transformed the sensation of historical realism and authenticity to a generalization.

The sculpture of Davit Guramishvili (1959-1965) also belongs to Merab Berdzenishvili's early creative period. In this work, external indications of movement are minimal. The single structural frame of the body, inclined toward flatness, is so precisely calculated, with key points marked and "attached," that any sensation of rigidity, inflexibility, or stiffness is entirely overcome. The slight angularity, alongside the stylistic features of the posture, evokes associations with the diverse outlines typical of the images of medieval ktetors. This preference for flatness may also be understood within this context, as the creation of the Guramishvili statue coincided with significant historical and political events. The processes occurring outside the boundaries in Soviet times were more accessible, though fragmented; there was an opportunity to return to one’s historical experience, a fact seen in the works of many artists, though often not fully realized and expressed spontaneously or even formally.

Merab Berdzenishvili. David Guramishvili. Cast iron. 1959-1965. Tbilisi

Despite its size and scale, the statue of Davit Guramishvili is not an odious or depressing figure; indeed, it is free of any sign of visual aggression, tailored to the city's urban landscape. Berdzenishvili skillfully employs this expressive approach in many of his other works (Muse, 1971). However, he is not unfamiliar with the aggressive differentiation that arises from the contrast between the form and its environment. In such cases, the dissonant artificiality and inorganic quality of the image become the primary means of expression (Medea, 1970; They Will Grow Even More, 1975; Didgori Memorial, 1986).

Merab Berdzenishvili. Didgori Memorial. 1986. (Architect Tamaz Gunia). Bronze. Detail

Merab Berdzenishvili. Didgori Memorial. 1986. (Architect Tamaz Gunia). Bronze. Detail

At various stages of his artistic career, he analyzed the distinctive features of the human body from different perspectives. In this regard, his series of nudes created with various materials is particularly significant. He also dedicated considerable effort to easel portraits.

Merab Berdzenishvili. The Muse. 1972. Bronze. Tbilisi

In 1988, a sculpture of Giorgi Saakadze, created by Merab Berdznishvili, was erected in one of Tbilisi's main squares. Equestrian statues were always among the most challenging of tasks for sculptors. Despite rich experience throughout the art world, each sculptor approaches the challenges anew, infusing their own unique perspective and style into their works. In this regard, Berdzenishvili is one of the most distinguished authors in the artistic circles, having created several notable equestrian sculptures in his career. His work began with the composition of King Vakhtang Gorgasali (1958, competition version), followed by the statues of Giorgi Saakadze (1970 in Kaspi; 1985 in Tbilisi). He later sculptured the central figure for the Kutaisi Victory Memorial (1981), and concluded with a statue of David the Builder in 1996.

The statue of Giorgi Saakadze, located in the center of a square in Tbilisi of the same name, stands on one of the tallest pedestals of the time period, impressive at the time when taken in relation to the scale of the city. The figure, which served as the visual highlight of the square at the time of its installation, became the central organizational element in the significantly enlarged space. However, today, the picture has changed radically: The statue of Giorgi Saakadze, along with various other factors, exemplifies how changes in the urban fabric of the city can dramatically alter the way a statue is perceived.

Merab Berdzenishvili. Giorgi Saakadze. 1985. Bronze. Tbilisi

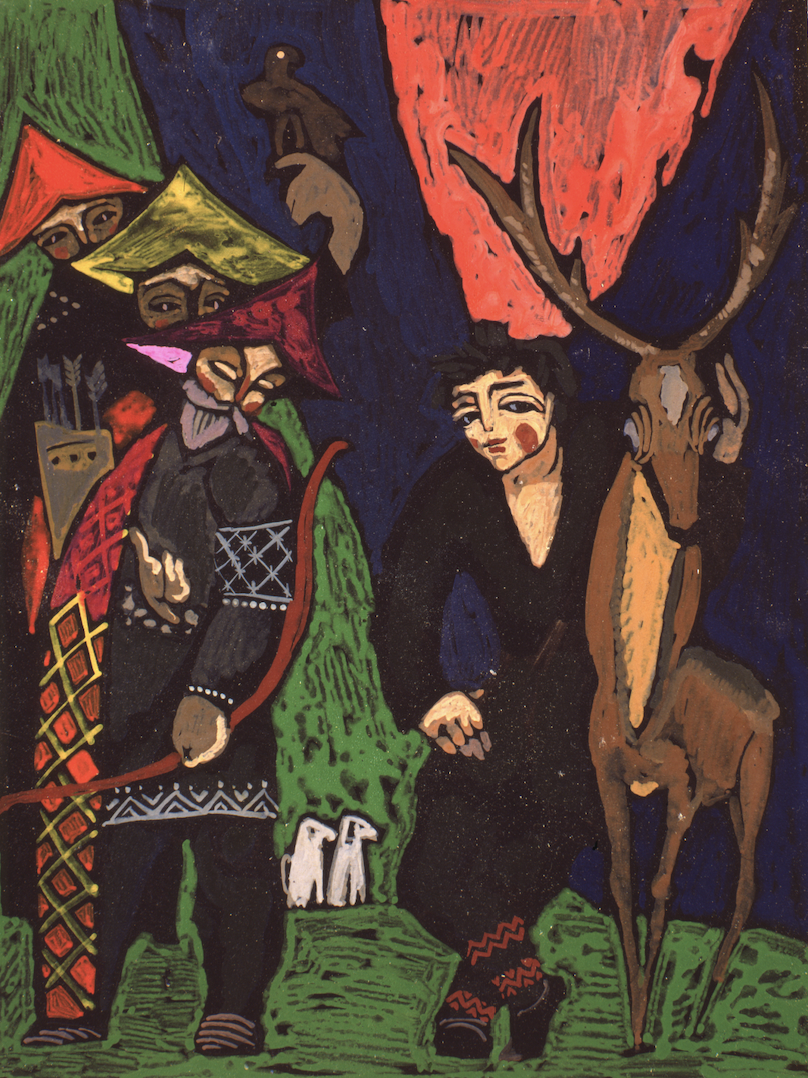

Alongside his statues, the author's creative legacy is represented by a variety of pictorial and graphic works, including book illustrations (Landscapes of Guria, the 1970s and 1980s; Winter in Guria, 1982; Portrait of a Brother, 1959; Laotian Sketches, 1974; Shepherd Boy, 1960; Kira, 1979; Sketches of sets and costumes for musical performance Komble, 1963; illustrations for Georgian folk tales, 1970s; posters for various plays, etc.).

Merab Berdzenishvili. Portrait of a woman. Oil, canvas. 35X29. 1998

Merab Berdzenishvili. Gurian Landscape. Paper, marker pen. 25X30. 1982

Merab Berdzenishvili. Illustration of a Georgian folk tale. Cardboard, gouache. 40X30. 1960

Merab Berdzenishvili. Illustration of a Georgian folk tale. Cardboard, gouache. 1970s

Merab Berdzenishvili left a deep creative legacy. Regarded as one of the most prominent sculptors in Georgian 20th century art, his diverse creative heritage and the uniqueness of his artistic-expressive language hold great significance. It is also important, to consider the historical context that the sculptor continually engaged with, as it serves to add depth and intrigue to the evaluation of his works.