Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Written sources provide a wealth of information about the medieval Georgian kings, with the primary among them being the chronicles, which were collected together in the Kartlis Tskhovreba (Life of Kartli; effectively The Annals of Georgia). The texts represent the lives and activities of the kings. The personal characteristics and physical appearances of the kings are also often described, although in a very general and often idealised manner. No matter how detailed or witty the characterisation of a person is, the desire to see his visual image is still great. Medieval Georgian art makes this possible through royal imagery.

This essay focuses specifically on royal portraits found in medieval Georgian wall paintings, although other historical figures, such as court officials, feudal lords, and clergymen, were also depicted in this art form.

Royal portraits are found in Georgian wall paintings from the 11th through the 17th centuries. They are usually accompanied by Georgian inscriptions.

It should be noted that the medieval images of historic figures can only conditionally be called portraits as per the modern understanding of portrait art. It was not a picture representing a person with all his individuality, as medieval art did not intend to represent a person in a naturalistic or realistic way. A medieval portrait was not an independent artefact, but part of a single decorative system - a wall painting, facade decoration, an icon. Therefore, along with certain individual features, the portraits followed the established rules and norms of medieval murals and were organically integrated into religious art.

Royal portraits are usually displayed inside churches which are either built or painted at the behest of the monarch in question. Consequently, they are presented as donors. However, royal images can also be observed in murals commissioned by non-royal donors.

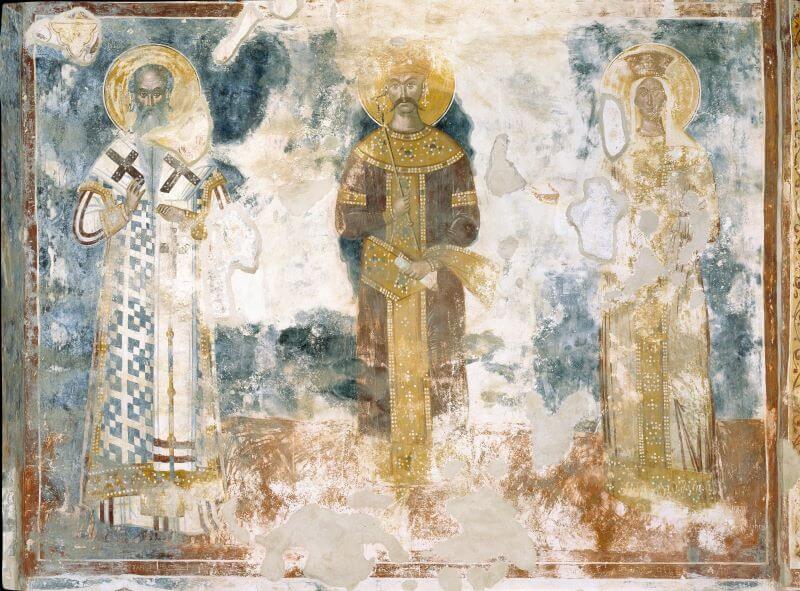

The aim of the royal images is to show the king's faith and devotion to God, his plea for salvation, and his donations - contributions to the building or painting of a church. The donation is, in essence, a gift given to God in the hope of salvation and eternal life. Thus, kings (as well as historic figures in general) are usually depicted in prayer, with their hands extended towards Christ, the Virgin, or a saint, in a gesture of supplication. The latter, in turn, address the king and bless him. Sometimes, a king is shown holding a church he ordered to be built or painted.

Besides, the royals obviously asserted also their power and glory via their images. In the wall paintings the kings looked as magnificent as possible, depicted in all their splendor and regalia, wearing richly embroidered royal robes with gold loros, and crowns embellished with precious stones. Unlike the non-royal figures, the royals were usually depicted with halos. It was believed that the king received his authority to rule the kingdom directly from Christ; thus, he was divinely chosen and could therefore be depicted with a halo.

Within the general scheme, kings are depicted in a variety of contexts, with each panel conveying a distinct meaning and message.

Medieval wall paintings established certain rules (patterns) for the depiction of royal images (and those of historic figures in general). They are placed in the lower zone of the murals, predominantly on the northern wall (occasionally on the southern or western walls), opposite the main southern entrance to the church. Thus, upon entering the church, the visitor is immediately confronted with the monumental image of the king. Moreover, the portraits are illuminated by the rays of light penetrating from the southern windows and door. In this regard, the images of George II (1156–11184) and Queen Tamar (1184–1213) in the Church of the Dormition at Vardzia, and the image of Demetre II (1259–1289) in the Church of the Annunciation in Udabno Monastery at Davitgareji are noteworthy examples. These portraits are the first images that capture the attention of viewers as they step into the churches.

Vardzia. Giorgi III and Queen Tamar. 1184-1186

Udabno. Church of the Annunciation. Demetre II. 1290s

Royal portraits are readily distinguishable from religious images. They have individual features (appearance, attire), and stand out for their considerable size, monumentality, and hieratic character, as well as for their solemn appearance. They are usually depicted against a plain background. Portraits of royalty of the 11th and 13th centuries are shown in a three-quarter position, standing in prayer before Christ, the Virgin, or a saint.

One of the earliest surviving royal images is found in the murals (second half of the 11th c.) of the quadriconch Sioni Church at Ateni. A group of historic figures is located in the lower register of the western apse. Due to damage, they have been identified differently. Yet scholars agree that the third image in the row represents King Bagrat IV (1018–1072). He is shown wearing a Byzantine royal robe and a jeweled crown. He is turned towards the Virgin, offering her a scroll. Despite the damage, the portrait of Bagrat IV remains impressive.

Ateni. Bagrat IV. 11th c.

At least five portraits of Queen Tamar (1184-1213), one of the most prominent monarchs of Georgia, have survived. In the Vardzia murals (1184-1186), Queen Tamar is depicted next to her father, Giorgi III. Similarly, in the Kintsvisi and Betania murals (early 13th c.), she is shown following Giorgi III, but this time is in turn followed by her son, Giorgi IV Lasha. In the Bertubani murals (early 13th c.), Tamar is depicted with her son. In all cases, the idea is to show the heirs to the throne, to express heredity and the legitimacy of the royal power (for the portraits of Queen Tamar, see:)

Kintsvisi. Giorgi III, Queen Tamar. Early 13th c.

A series of royal portraits from the 13th to the 17th century can be found in the Gelati monastery, which was founded in 1106 by Davit IV the Builder (Aghmashenebeli, 1089-1125) as a burial place for Georgian kings. The wall paintings of both churches, those of the Cathedral of the Nativity of the Virgin and the Church of St. George, contain a considerable number of royal images.

The murals of the south-eastern chapel of the Virgin Nativity Church, dated to the late 13th century, feature two portraits of Davit VI Narini (1245-1293). He is depicted as both a king, wearing a royal robe and a crown, and as a monk, clad in monastic attire. This is a unique example of medieval Georgian wall paintings depicting a single person in two distinct roles simultaneously. Despite the similarity in appearance, the two images of the king evoke different impressions. The royal portrait is characterised by a formal and hieratic quality, while the portrait of Davit the monk is imbued with a sense of emotionality. The chapel served as Davit Narini’s burial place.

Gelati. Church of the Virgin Nativity. Davit Narini as a monk. Late 13th c.

Gelati. Church of the Virgin Nativity. Davit as a king. Late 13th c.

The group of donors displayed in the lower register of the northern wall of the Gelati church of the Virgin Nativity dates from the 1560s. The panel unites the images of Davit IV the Builder, the founder of the monastery, and those of the donors, who commissioned the murals in the 16th century.

The group is headed by Davit IV and followed by the Catholicos of Western Georgia, Evdemon Chkhetidze (1557-1578), the kings of the Imereti kingdom Bagrat III (1510-1565) with his wife, and Giorgi II (1565-1583) with his wife and son.

Gelati. Church of the Virgin Nativity. Donor portrait. 1560s.

By the time these murals were executed, Davit IV was no longer alive. However, the donors of the murals – George II of Imereti and Catholicos Evdemon – considered it important to include his image in the panel given that Davit IV was the founder of the monastery and the builder of the church. This is precisely how he is portrayed here, as a donor, with the church in his hand. This imbues him with particular significance and sets him apart from the other figures. At the same time, being presented alongside Davit IV would be important for the Kings of Imereti. By placing his portrait at the head of the royal row, the 16th-century kings sought to underscore their lineage from Davit IV, the supreme ruler of the unified Georgian state, while simultaneously expressing their esteem and respect for him as the founder of the Gelati monastery.

Gelati. Church of the Virgin Nativity. Davit IV the Builder, Cathalicos Evdemon. 1560s.

Gelati. Church of the Virgin Nativity. Girogi II of Imreti. 1560s.

It is noteworthy that Davit IV and George II of Imereti are depicted wearing similar green robes, decorated with floral ornaments and loros, while the attire of Bagrat III is relatively simple, without ornamentation. It seems that the primary donors, David IV and George II of Imereti, are accentuated through their richly decorated clothing. The robes of George’s wife and son are also decorated.

It is assumed that the portrait of Davit IV replaced his original image, which had evidently suffered damage, which is quite likely. A number of hypotheses have been proposed regarding the existence of Davit IV’s portraits in the 11th-12th-century wall paintings. However, the Gelati image is the only surviving portrait of David IV in good condition, accompanied by an inscription, and so it is therefore of particular importance. It is noteworthy that the image of David IV is also depicted on a 12th-century icon of the Monastery of St Catherine on Mount Sinai.

Kings of Imereti, Bagrat III and Giorgi III, are also depicted in the Church of St George in the Gelati monastery.

Gelati. Church of St. George. Catholicos Evdemon, Bagrat III of Imereti and his wife. 16th c.

Gelati monastery has preserved a number of 17th-century royal portraits as well. The murals in the north-eastern chapel of the Virgin Nativity church were commissioned by King Giorgi III of Imereti (1604-1639) to serve as his family burial chapel. Upon entering this small chapel, the viewer finds himself surrounded by the portraits of Giorgi III of Imereti and his family members, including his spouse, children, parents and brothers, occupying the lower register of all three walls. Standing frontally close to the floor level of the chapel, they gaze towards the viewer. Giorgi III and his consort are dressed in royal robes and crowns. However, the garments are less opulent than those worn by earlier royal figures.

Gelati. Church of the Virgin Nativity. Giorgi III of Imereti with his wife and son. 17th c.

The royal images of the 16th -17th centuries, in contrast to the portraits from the 11-13th centuries, are shown in frontal poses. This became the standard posture for historic figures from the 14th century onwards. The style of royal attire also underwent alteration. During the 11th and 13th centuries, royal gowns were heavy and had a straighter pattern. From the 14th century onwards, garments with a more cinched-in waistline were adopted. The Late Medieval portraits are no longer as monumental and sumptuous as those of the 11th-13th centuries, lacking the artistic qualities of the earlier murals. However, there are some truly remarkable royal images. In this regard, the portraits of the 16th century kings of Kakheti are of particular note.

The patronage and donor activities of Levan II of Kakheti (1518-1574) are attested in several churches, as evidenced by the presence of his donor portraits. In addition, he and his successor, Alexandre II, are depicted as donors in the murals of the refectory of the Philotheou Monastery on Mount Athos. However, the donor portrait of Levan and his family members in the Church of Nekresi is a really outstanding example of late medieval portraiture. It is highly probable that the painter responsible for the Nekresi murals was a Greek. This hypothesis is supported by the murals themselves, which reflect the most advanced trend of Post-Byzantine paintings, as well as by the donor inscription in Greek in close proximity to the portraits.

Nekresi. Levan II of Kakheti. 16th c.

In considering the subject of medieval royal imagery, it is necessary to recall the scenes of coronations. Of particular interest is the panel from the Church of the Saviour in Matskhvarishi, created in 1140, which displays the coronation of King Demetre I (1125–1156). The composition depicts Demetre I receiving a blessing from Christ, while the archangel Gabriel crowns him, and two eristavs (local rulers) gird him with a sword. The scene reflects a real coronation ceremony, including both the ecclesiastical and secular elements.

Matskhvarishi. Coronation of Demetre I. 1140.

Another panel depicting a coronation can be found in the northern porch of the Virgin Church in the Gelati monastery. The panel, dating from the 1520s, shows the coronation of Bagrat III of Imereti.

Gelati. Coronation of Bagrat III of Imereti. 1520s.

The subject of royal imagery in medieval wall paintings is so vast and complex that it is beyond the scope of a single essay. Yet it is absolutely evident that royal imagery constitutes a valuable contribution to medieval artistic heritage. It is also of considerable historical importance, reflecting the cultural and political contexts of the time.

The information about Georgian kings preserved in textual sources, and their images in medieval wall paintings, complement each other and provide insight into the royal personalities. The portraits show the appearance of the kings, their attire and insignia, and their activities as donors and so on. The inscriptions accompanying the royal images are also of great importance, as they often provide unique information about the kings, their activities, or historical circumstances.