Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

During and after the October Revolution of 1917, Georgia, and particularly Tbilisi, became a refuge for exiled, gifted artists, many of whom had a significant impact on the development of Georgian fine arts. Among them was the renowned Russian painter and graphic designer Vasily Shukhaev.

Vasily Shukhaev

Vasily Shukhaev was born in Moscow in 1887. He attended the Stroganov Central Art and Industrial School in Moscow and, after graduating, continued his studies at the Department of Painting and Sculpture of the Higher Art School at the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg. Shukhaev began studying under the famous tutor Dmitry Kardovsky in 1908, who greatly influenced him.

Vasily Shukhaev spent the most of his life in France, where he worked in easel and monumental painting, creatively illustrating books and journals, and collaborating with Ida Rubinstein, Nikolai Baliev's theater ‘Ghamura,’ and the Paris theater ‘Balaganchik.’ He worked with Jacques Shifrin's publishing company ‘Pleada.’ His caricatures of modern political personalities appeared in the American magazine Vanity Fair. Shukhaev also taught sketching at his own art school.

Shukhaev traveled extensively with his wife, Vera Shukhaeva, and their friend, Alexander Yakovlev, to southern France, Spain, and Morocco. His everyday and creative life was both lively and secure.

Vasily Shukhaev. In Auvergne. Canvas, tempera. 78x60,5. 1926

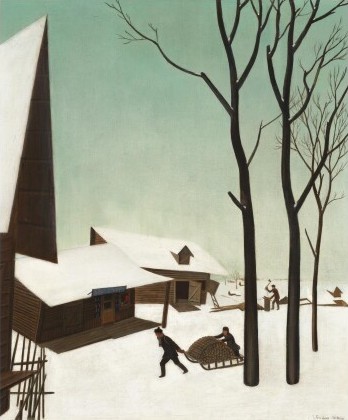

Vasily Shukhaev. Snowy day in Finland. Canvas, oil. 1921

Yet, Vasily Shukhaev, who had fled Soviet Russia in 1920, chose to return to his country in 1935 - by then already the Soviet Union. He was full of optimism, but his fate was predictable. Like many other artists who returned from emigration, he was imprisoned in 1937 on espionage allegations and deported to Magadan, on the Kolyma River. The Shukhaev couple was released in 1947, but they were not allowed to settle in large cities. They traveled to Tbilisi on the advice of a friend.

Vasily Shukhaev. Landscape. Paper, watercolor. 31x44. 1970. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Vasily Shukhaev. Sketch of the curtain. Cardboard, watercolor and gouache. 37x54. 1940 - 47s. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Thereafter, the Shukhaev couple's life and work became inextricably linked to Georgia: Tbilisi and the country as a whole were more than merely the sites of their forced relocation. Georgia became a country where artists could live and develop, and so, despite the hardships, Vasily Shukhaev never thought of leaving Georgia. Tbilisi was his choice, and Georgia became his second home.

Shukhaev's contribution to the development of Russian modernist art is enormous, as is the creative legacy he left while residing in Georgia, the majority of which he bequeathed to the Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Art. In 1954, Vasily Shukhaev held a solo show in Tbilisi, at the Exhibition Hall of the Union of Artists of Georgia. This was his inaugural show following his decade-long exile. Through much effort, Shukhaev assembled the artworks from 1910 to 1930 in Tbilisi, which had been kept in Leningrad until his arrest. The emphasis of those works was primarily on avant-garde culture and art when studying Russian art of the 1900s-1920s.

At the opposite end of the artistic spectrum, neoclassical artists endeavored to convey the contemporary era through the language of classical art. In contrast to the Russian avant-garde, these artists were enthusiastic about reintroducing the classical traditions of painting that had been practiced by ancient artists to the fine arts. Though he did not participate in the revolutionary attempts of avant-garde artists to reimagine visual language, Vasily Shukhaev remained persistent in his pursuit of a personal artistic methodology, which led to shifts in his quantitative and qualitative understanding of the world, how he portrayed it, and the visual techniques he employed. At times, these shifts even veered into eclecticism. The artist's letters to friends and his instructor Dmitry Kardovsky reflect this: "There are several good places in the picture, but there is no unity; the style of the whole picture is not completely clear." This sentiment is echoed in the artist's works from 1911–1920.

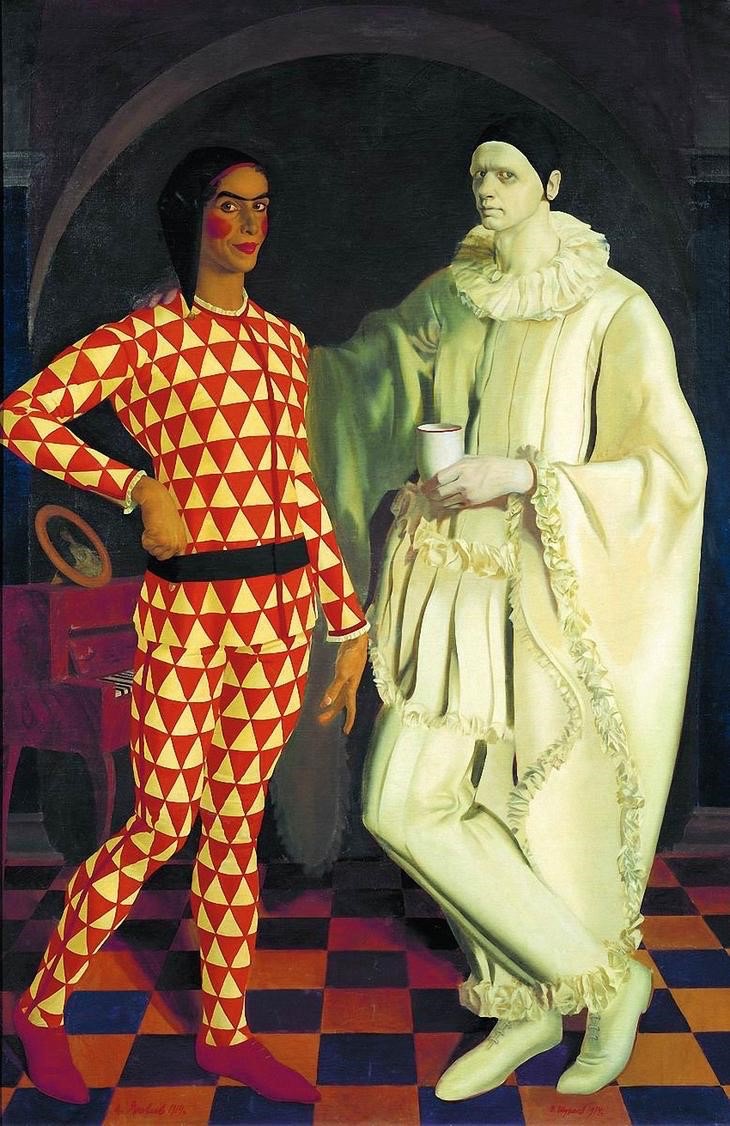

Vasily Shukhaev, Alexander Yakovlev. A. Self-portraits, Harlequin and Pierrot. Canvas, oil. 210x142. 1914 (The work was finished by V. Shukhaev in 1962). Russian Museum

Vasily Shukhaev and Alexander Yakovlev's ‘Double Self-Portrait - Harlequin and Pierrot’ was an outstanding product of their creative partnership and a programmatic piece of Russian neoclassicism, created while on a business trip to Italy in 1914. The creators' characteristics and personalities are contrasted in ‘Harlequin and Pierrot.’ Before that, at Meyerhold's Theater ‘House of Intermediaries’ in St. Petersburg, youthful performers had successfully portrayed the roles of Harlequin and Pierrot. In the artwork, Yakovlev portrayed Harlequin and Shukhaev Pierrot; each man depicting himself. Even though the painting adhered to academic art rules, there are still signs of modernism within it. The neoclassical aesthetic is filled with the angularity of cubism and distortion of forms of neoprimitivism, as well as theatrical stances, color contrasts, and character expressions seen on the faces. Around the same time, artists were drawing inspiration from the Renaissance to produce narrative compositions and portraits of exceptional quality.

Vasily Shukhaev. Portrait of Madame Andreeva. Paper, sanguine, sauce. 147x103. 1921. Moscow Museum of Modern Art

While creating the 1917 ‘Portrait of E. Shukhaeva,’ the artist made use of a technique that had long been forgotten. Vasily Shukhaev devoted much of his time as a student to studying the ins and outs of encaustic, gold writing, and glazing techniques. The picture's foundation is adorned with golden leaf, and the color is brought to life by the meticulous execution of the woman's opulent draped clothing, which features delicate subtleties and glazing. Years later, in 1956, in Tbilisi, Shukhaev used a similar technique in his ‘Portrait of Nino Tumanishvili’ (Woman in a Silk Dress), elevating the depiction even further.

Portraits of St. Petersburg beauties are another key aspect of Vasily Shukhaev’s work. We are particularly interested in the artist's portraits of Salome Andronikashvili. The sanguine portrait painted in 1917 is one of the artist's most important works, displaying the characteristics of both classical and contemporary art with equal intensity and emotion. Shukhaev painted Salome Andronikashvili's portrait twice in the 1920s, while in exile in France. In 1921, the artist created sketches for the painting ‘Salome in Red Stockings’ using the sanguine and sauce techniques, and again in 1922, for a large-scale oil painting composition, the current location of which is unknown and is only known about from a reproduction in an issue of the magazine Paskunji/ Phœnix. Shukhaev showed a picture of Salome Andronikashvili-Galperni at the Galerie Barbazanges in Paris in 1922.

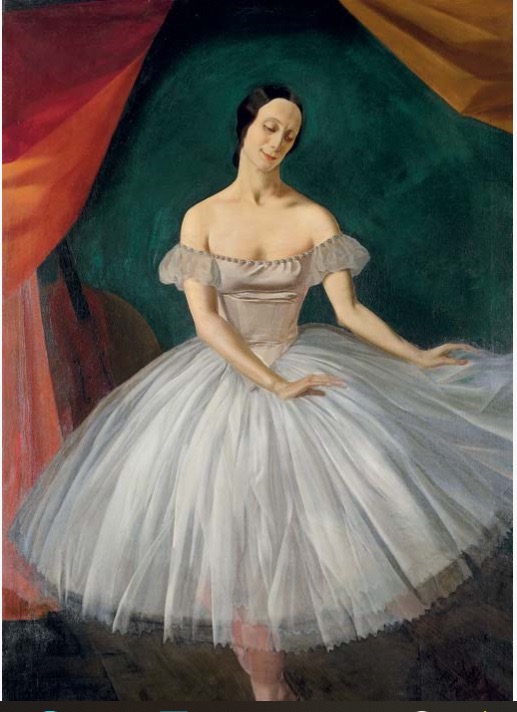

Vasily Shukhaev. Portrait of Madame Pavlove. Canvas, oil. 186x119. 1920.

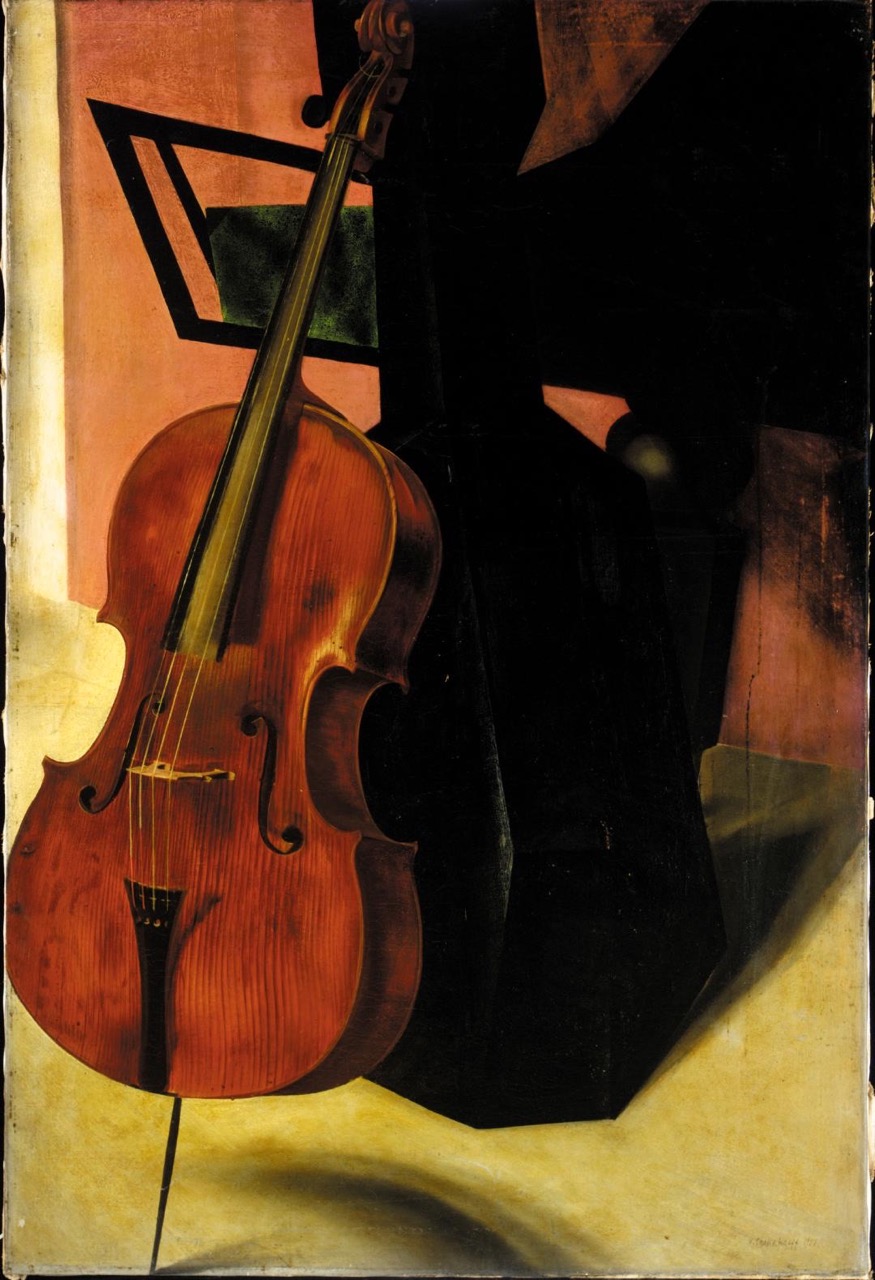

Vasily Shukhaev. Cello. Canvas, oil. 135x91.5. Private Collection

The compositions of these portraits are the same, but their artistic solutions differ. In the sanguine painting, the psychotype of Salome Andronikashvili—a self-assured, arrogant, and noble woman—is revealed, along with the traits that defined her personally. The effect of the painted portrait is very different, focusing on the compositional-coloristic challenge rather than displaying the model's personality. Salome Andronikashvili claimed that the artist was influenced by Zurbaran’s work, which is on display at the National Gallery in London.

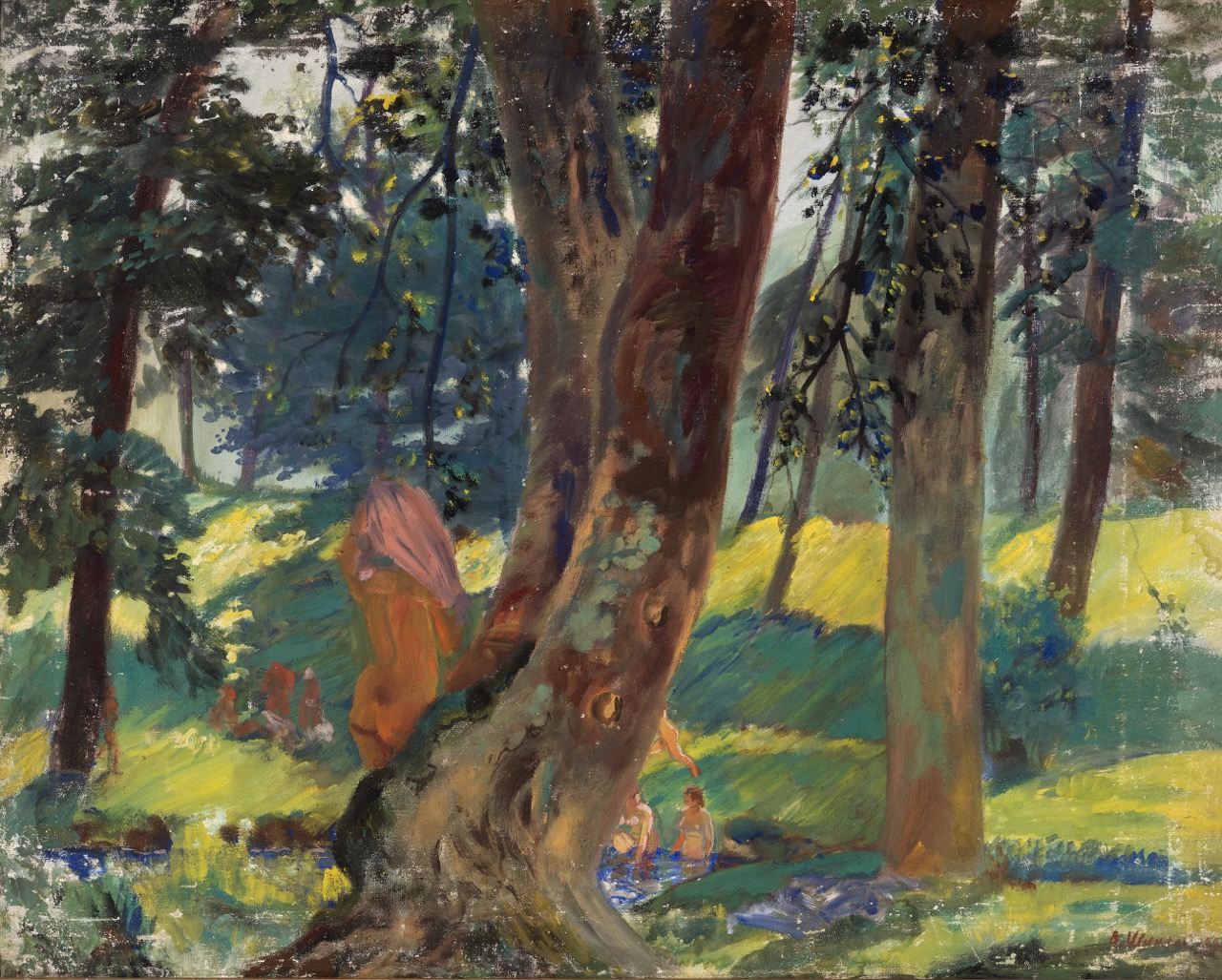

Salome Andronikashvili also appears in the large-scale work ‘Picnic,’ a paraphrase of a familiar scene in European art. It depicts people in nature, half-naked. The figures are painted according to a photograph taken by Vera Shukhaeva in the 1920s. Behind the "lace" of the brown, strongly defined bodies of trees push near the viewer, giving a perspective that resembles the grayish foam of the sea or the sky stretching out. The composition, focused on figurative-formal contrasts, centers on the group of people lost in the vastness of nature. The expressive solution of the environment emphasizes the idyllic mood of the human group.

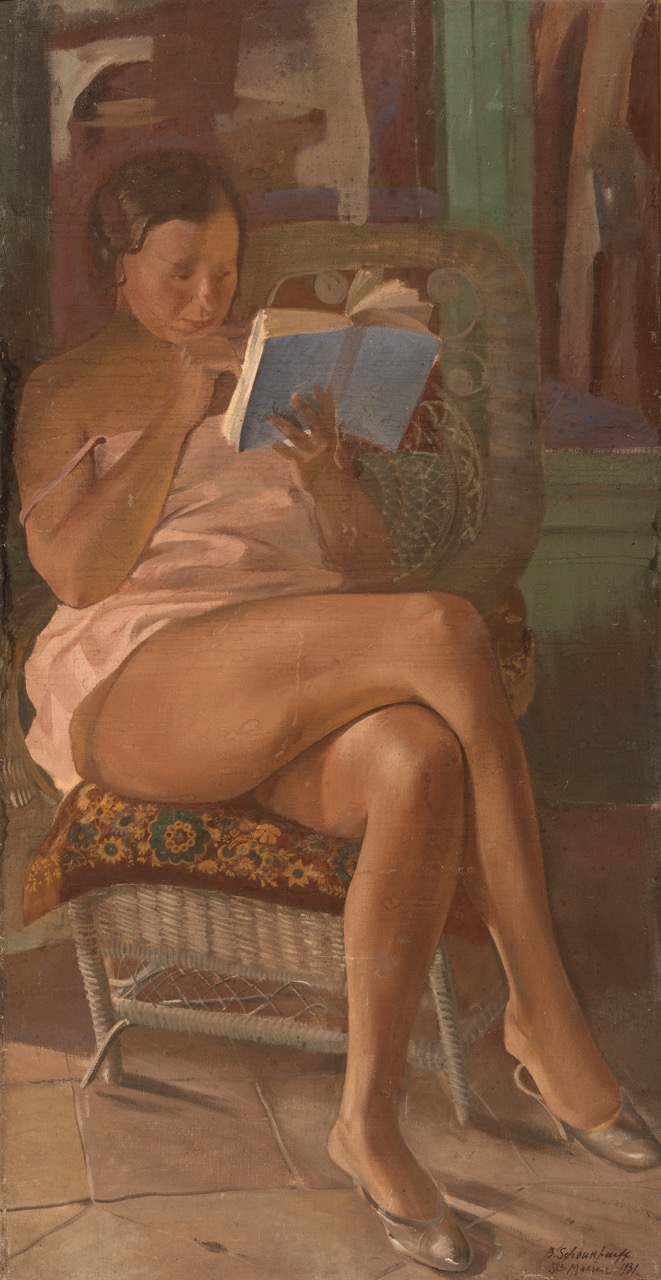

Vasily Shukhaev. Portrait of Lyalya Moskovskaya while reading. Canvas, oil. 150x79. 1931. Art Museum of Georgia/GNM

Vasily Shukhaev. Portrait of Olya Rudik. Canvas, tempera. 99,5x90. 1970. Art Museum of Georgia/GNM

In the landscapes that Shukhaev painted in Finland and France between 1920 and 1924, there are hints of cubism and neo-primitivism. While keeping the descriptive power of line and shape, the artist builds the structure of the piece by rhythmically arranging colored planes. The regular shapes of the images, the metallic gloss of objects, the skewed perspective, the broken-up order of the composition, and the contrast between dark and light planes give these pieces a unique expression. ‘Province’ (Russian Landscape, 1923) is one of few interesting and masterfully put-together pieces of this style created by the artist. Others are ‘Still Life with Salt and Chimney’ (1921), ‘Street, Province’ (Finnish Village, 1921), ‘Village Scene’ (Finland, 1920), and ‘Finnish Village. Roofs’ (circa 1922).

In some instances, Shukhaev’s landscapes seemed like theatrical decorations. It is interesting to note that the laconicism of the artistic language in his ‘Winter Landscape,’ painted in Finland, as well as the rhythm of dark silhouettes of people and objects in a snowy environment, reminiscent of Pieter Bruegel's aesthetics, can also be found in Elene Akhvlediani's painting ‘Winter’ from 1924. This similarity is intuitive, arising from a shared sphere of interests. Though they did not know each other at the time, later, similar scenes became common in the landscape paintings of both Vasily Shukhaev and Elene Akhvlediani.

In France, Shukhaev traveled and worked mostly in the landscape genre. His art seldom contained images that elicited an emotional response; rather than viewing the world via his senses, he seemed to be merely a contemplative observer. The artist was frequently criticized for his paintings' "lack of pictorial sensitivity and creative flight." However, Shukhaev considered this to be organic. He worked with line, light, and shadow, with color playing a secondary role in body formation. Shukhaev may have had a slightly stronger drive for technical excellence in execution. Unlike his friend and collaborator, Alexander Yakovlev, whose “world is bright and moving, silent, with a playful virtuosity,” Shukhaev’s world was dark and static, with a phlegmatic desire for perfection.

The still life in Shukhaev's work provides a unique conceptual and formal solution, serving as a visual diary of time and phases in the artist's life. The emotional mood of these mostly ascetic still lifes is sad, not sentimental, but filled with a sense of the loss of important values. They convey the feeling of a forced change in an already established way of life, or the unconscious fear of an uncertain future. This is especially true for the still lifes created during the 1910s and 1920s. This atmosphere fades and reappears in his Georgian still lifes. Shukhaev's still lifes are mostly self-sufficient and self-contained, with little interaction with the observer. With few exceptions, they do not evoke the mood of life, abundance, pleasure, or joy derived from beautiful objects. I believe this is one method to demonstrate man's separation from the world.

Vasily Shukhaev. Bouquet. Canvas, tempera. 81,5x65,5. 1953. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

After arriving in Georgia, views of the southern French coast and small towns were replaced with Georgian scenery. The artist became more interested in views of mountains, spruce woods with sunny fields, and forests spread across the hills. Most of these scenes are executed very professionally and adhere to a realistic art style. Though there were some exceptions, Shukhaev's works from this time fit perfectly into the Soviet art system. This was not because the artist had to conform to the rules of socialist realism, but because the neoclassicism style, which is based on classical art, was the formal language of socialist realism.

The majority of the people depicted in Shukhaev's portraits, which are primarily tempera paintings, were members of the artist's intimate circle during his time in Georgia. In large-format compositions, the figures are displayed against neutral backgrounds or with attributes indicating their profession, allowing the artist to more accurately capture the model's personality.

Shukhaev was a talented graphic artist. His portraits and compositions created using the sanguine technique hold a significant position in the history of European graphic art. In Georgia, Shukhaev focused primarily on portraiture and produced a series of representations of Georgian culture. His graphic portraits of Georgian authors are particularly significant. The contrast between the volumes of the face and hands, which are painstakingly molded with sanguine's red tonal transitions, and the white hue of the sheet, which simultaneously gives the sensation of space, is striking. Naturally, this compositional solution highlights the hands and eyes, symbolizing the inner lives of these utterly different individuals.

Vasily Shukhaev placed a high moral value on his relationship with Elene Akhvlediani. The great Georgian painter, along with her female artist friends, often visited Tsikhisjvari, where the Shukhaev family spent their summers. They often took part in sessions of plein-air painting. Georgia's natural beauty and vibrant hues, along with Shukhaev's friendly and creative relationship with Elene Akhvlediani, may have contributed to the increased painterliness of the works from the final period of his creative life. The joint plein-airs in Tsikhisjvari between these two great artists were not without creative mutual influence. Shukhaev may have been influenced by the decorativeness of color which was the hallmark of Elene Akhvlediani's creative philosophy.

Vasily Shukhaev. Tsikhisjvari, bathing women. Canvas, tempera. 66x91. 1959

Throughout his lengthy artistic career, Vasily Shukhaev created numerous self-portraits. One of the final ones is ‘Self-Portrait in a Yellow Jacket.’ Against the backdrop of the picture ‘Celebrating the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Soviet Authority,’ the artist portrayed himself in the studio. The artist, who had recently returned from France, once said, “It is generally difficult for an artist to talk about himself, and I feel exactly like that now. My illustrations, paintings, and sketches tell the story of my artistic journey.”