Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Temo Japaridze is one of the most prominent representatives of Georgian Soviet art. Although he belonged to the generation of the 1960s and 1970s, he greatly differed from his contemporaries in his courage, exploration of existentialism, intuitive coherence in relation to time, and immense individuality. From the 1950s to the restoration of Georgia's independence, several Soviet artists experienced "artistic crucifixion" or "Golgotha." Temo Japaridze was among them through his creativity, being perceived as the "leader" of a modern, unified, systematized fabric of Georgian art. From the 1960s until his death, Temo created extremely unconventional pieces, as if he had never lived in the Soviet Union and was immune to its collective ideological censure. Above all, what always fascinated me about Temo was his creative hunger, spontaneous innovation, and perception of modernity. Having studied at the Faculty of English Philology, he was not an artist by trade, and that is why he stood apart from the handwriting and stylistic influences typical of many generations of artists. His creative work is abundantly rich in narrative prose and poetry, civic attitude in urban-social settings, and time-space absorbed by the introverted-existentialist psychologism of a man...

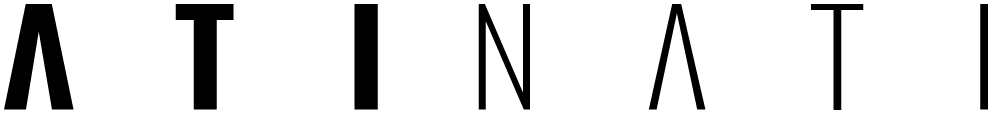

Temo Japaridze. Feast. Oil, cardboard. 40x50 cm. ATINATI Private Collection

Temo Japaridze was born in Tbilisi on March 27, 1937. From a young age, he was captivated by poetry and painting. He earned a degree in 1964 from the Faculty of Western European Languages and Literature of Tbilisi State University. Beyond his artistic talent, Japaridze was also a writer (Niko Pirosmani: Life and Creative Work, 1999), a poet (Passions of a Mad Woman: A Collection of Poems, 2000), and an essayist (The Silence of a Painting: A Collection of Essays, 2010). He was significantly influenced by the “Vera Garden” - an anti-Soviet group representing an urban subculture. A number of public and cultural figures convened there, among them Anzor Salukvadze, Shota Chantladze, Erlom Akhvlediani, Guram Rcheulishvili, and Rezo Kiknadze.

Anti-Soviet consciousness was formed in Japaridze at that time, coming to be later expressed in his writings and artwork. He tried taking his poetry to the editorial office to be published in the magazine ‘Tsiskari.’ The editors loved the poems, but refused to publish them, since they did not exude Soviet optimism and were deemed too pessimistic by the censors. Yet Japaridze's brilliance was recognized by his friends and acquaintances, including Shota Chantladze, Anzor Salukvadze, and Guram Rcheulishvili. The same editorial office also refused to publish Japaridze's story ‘The Patriot.’ After seeing the film ‘Modigliani’ in cinema house Spartak, fine arts were added to the artist’s inspiration.

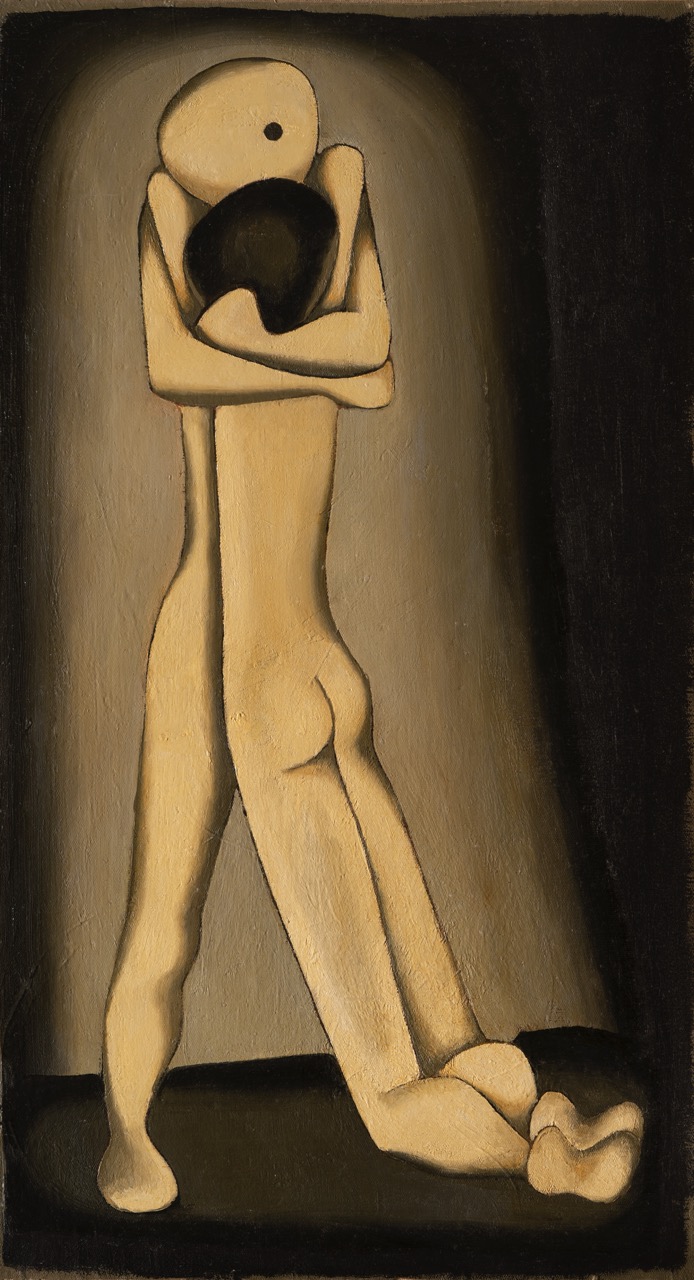

Temo Japaridze. Red Woman. Oil, canvas. 118x46 cm. 1960s. ATINATI Private Collection

Temo Japaridze created a plethora of paintings, graphics, sculptures, and collages from the 1960s until his death. His works were exhibited in the Artist's House (1968), Georgian Artists Union (1965), the TSU Assembly Hall (1964), and in Paris and Brittany (1991). He passed away on September 27, 2012, at the age of seventy-five.

Two biographical facts had an impact on Temo Japaridze's work - the University Assembly Hall Exhibition (1964) and the painting ‘The Secret Supper’ (created in 1972), which was destroyed in a fire at the Artist's House during the Civil War.

Japaridze held his first exhibition in the Assembly Hall of Tbilisi State University in 1964. This was one of the first non-conformist exhibitions in the post-Soviet art space. The latter preceded the 1974 ‘Bulldozer Exhibition’ by 10 years, which revealed the brutal Soviet communist system's censoring practices to the world. Japaridze's exhibition was ambivalent, resonant, alive; with it, he confronted Soviet officialdom, the essence of salon and socialist art. The exhibition was evaluated by different determiners - it was labeled anachronistic, bourgeois, anti-Soviet, non-Georgian, and even slightly Western, making it "inappropriate" for the Soviet visual-ideological program. Lado Gudiashvili and Shalva Amiranashvili, however, estimated Japaridze's expressive language as Georgian, national, new, and thoroughly integrated with European creative traditions. The strict position and lack of acceptance from the officialdom was expressed by the following phrase – “Look at Temo's paintings. Will his people - such thin, weak people - build socialism and communism?!” In 1968, the building of the Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries hosted an exhibition of Japaridze's abstract paintings.

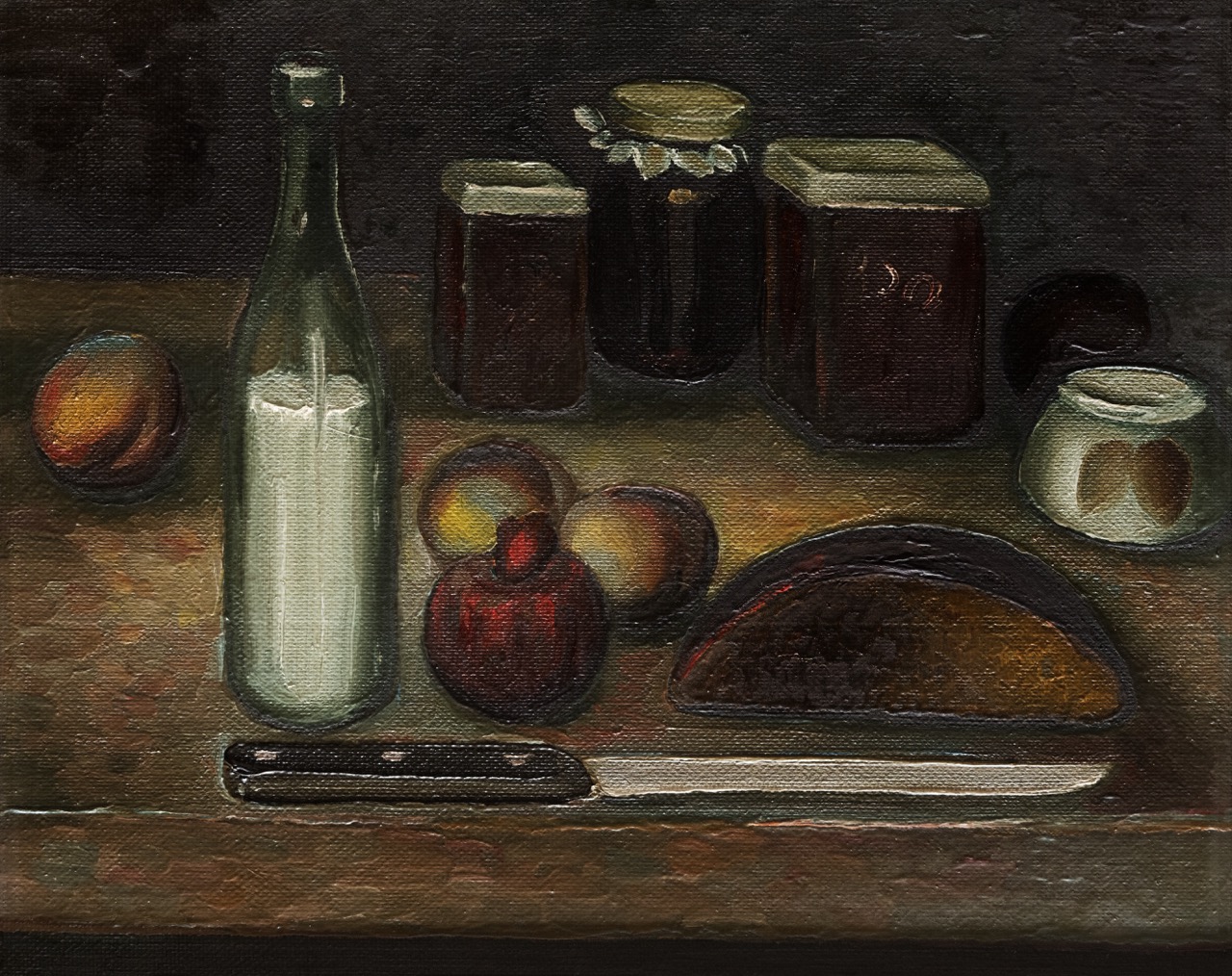

Temo Japaridze. Portrait of a Woman. Oil, cardboard. 70x50 cm. 1965. Diptych. ATINATI Private Collection

Temo Japaridze. Abstraction. Oil, cardboard. 70x50 cm. 1965. Diptych. ATINATI Private Collection

Abstract art was, in those days, equated to formalism, and had been banned since David Kakabadze's time. The exhibition was closed within three days due to the intervention of the KGB, but, before that, excited visitors all but smashed down the doors to catch sight of Japaridze’s art. Such a public outcry highlighted the fragility of the communist system and its degradation in people’s consciousness.

Because of these two resonant exhibitions and the artist’s free, creative thinking, Temo Japaridze came under the KGB’s spotlight. That is why such an immense assemblage as ‘The Secret Supper’ was, for security reasons, created in Tamaz Chkhenkeli's apartment on Khiliani Street in 1972; later it was moved to Malkhaz Gorgadze's garage. The unusual fact was reflected in a German publication, and an irritated visiting journalist published an article titled ‘Christ in the Garage.’ Temo Gotsadze, the director of the Artist’s House, displayed the work in Japaridze's personal show, but during the civil conflict in 1991-1992, the Artist's House containing ‘The Secret Supper’ was destroyed by fire.

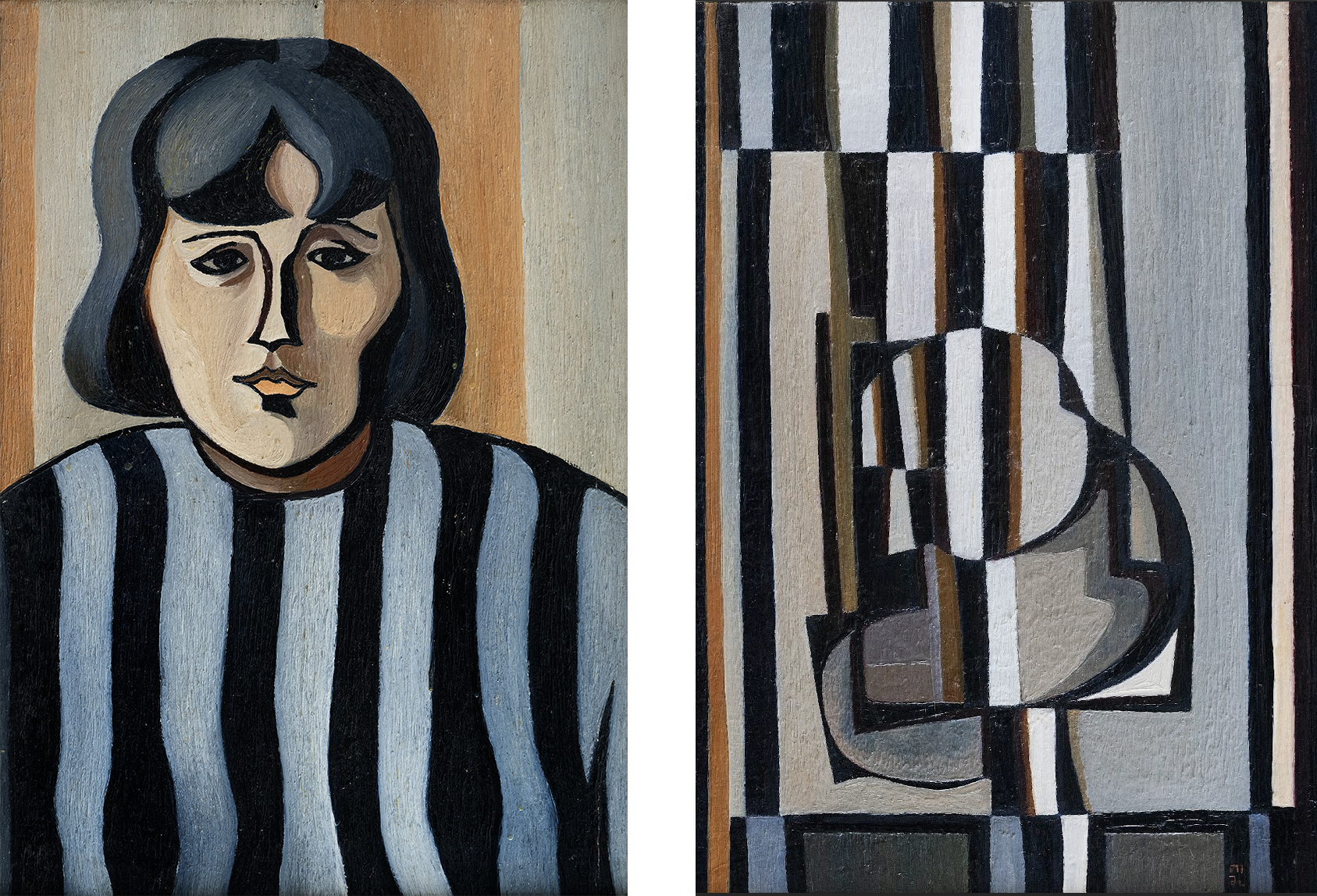

Temo Japaridze. Still-Life with a Pipe. Mixed media, canvas. 27x25,7 cm. 1978. ATINATI Private Collection

The artist's biographical dramaturgy, conditioned by actual circumstances, might be freely called "Soviet Golgotha" or "artistic crucifixion." The system did not forgive the artist for infusing Western, national, humanistic, individualistic, and formalist aspects into communist thinking, thus shattering artistic isolationism.

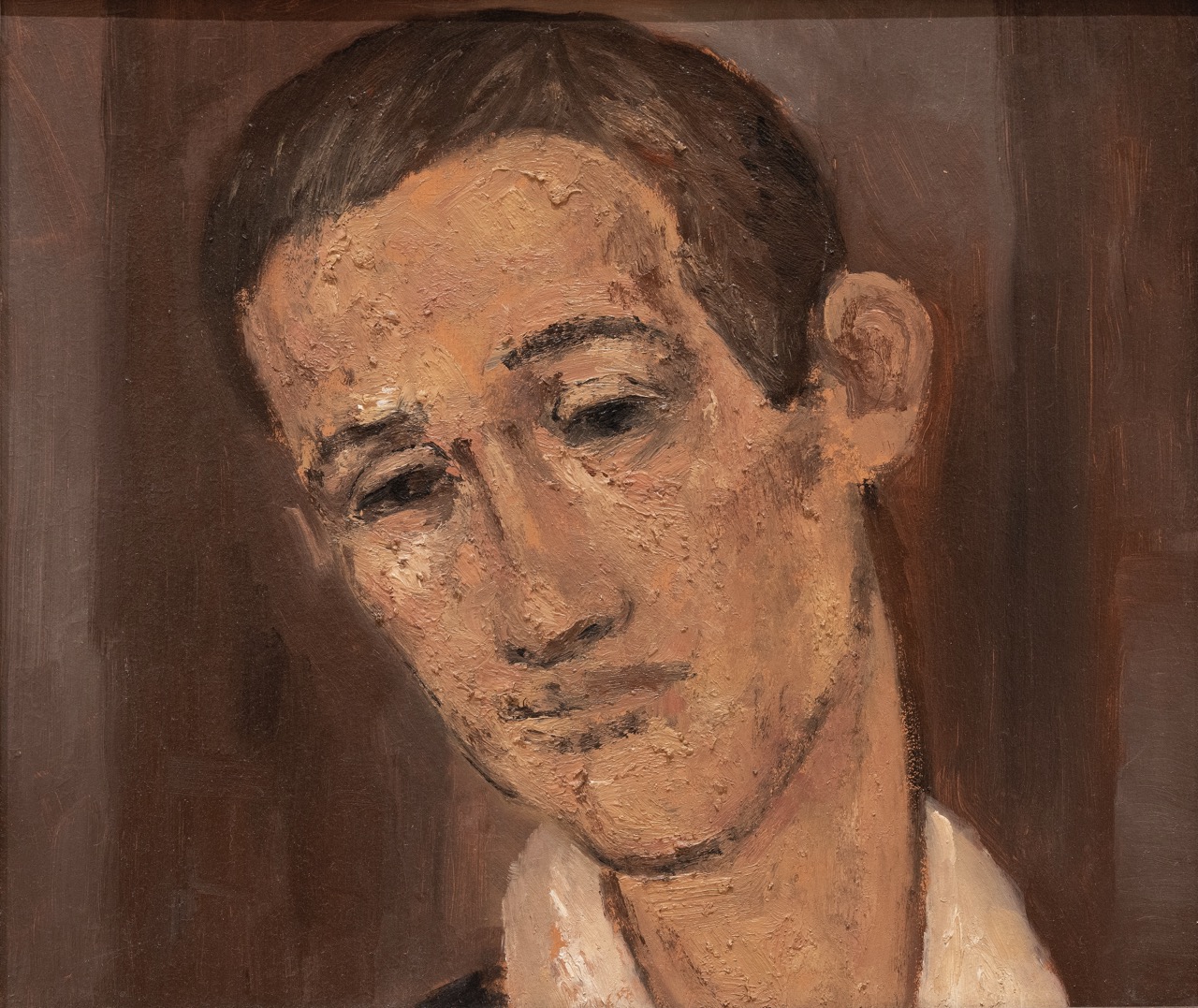

Temo Japaridze. Portrait of a Man. Oil, cardboard. 34x40 cm. ATINATI Private Collection

Temo Japaridze's work appears to be typical of nonconformist art, which is stylistically diverse and encompasses cubism, pointillism, existentialism, abstractionism, pop art, neo-expressionism, and surrealism... The list of styles is endless. He was not an adept or orthodox of any particular one; on the contrary, he broke them down here and there. He would “Georgianize” them moderately, emerging as an artist with his own destiny, in a time and space that he could not choose; he struggled and often failed...

Temo Japaridze. Landscape. Oil, cardboard. 50x70cm. ATINATI Private Collection

Japaridze is interpreted in Western art within the broad term of “outsider art”- art that is ahead of its time, and it was especially so during the Soviet era. Characters, mise-en-scènes, objects; his fragile, lonely, introverted, existentialist, and escapist world are all rather wild and raw. It is often the case that the art of outcasts gains popularity and public recognition following the death of artists working in this genre; possibly, Japaridze's pieces were no exception.

Temo Japaridze. Return. Oil, canvas. 90x49 cm. 1967. ATINATI Private Collection

In the 1960s, Temo Japaridze created primarily abstract and surrealistic artwork. Formalistic studies, dreamy flow or absurdity; a sensation of exclusion rather than loneliness, and the distortion of human appearance unite the works of this time. One may read somber chroma, stylized plasticity, and the individual's separation from society in the objects, sculptures, and assemblages of the 1970s. Identical nuances appear in his paintings of the 1970s, yet themes, scenes, stylistics, and portraits characteristic of the Tbilisi School of Painting dominate in his dark brownish works.

Temo Japaridze. Portrait of a Man. Oil, mixed media, plywood. 64x38 cm. 1971. ATINATI Private Collection

Japaridze's paintings became increasingly vibrant, sensual, neo-expressionistic, and occasionally even primitively modeled in the 1980s and 1990s. His breaking away from the Parisian School's conventions and echoes of "Art Brut" or "outsider art" became clearer in the works of these later decades. Human flexibility loses its physicality and becomes a cruel, stony mass; the crumpled texture of the canvases increases vulnerability, the chaotic spirit of the world and the fragility of man within it; fictitious figures and social beings somehow try to leave the pictorial plane - the world...

Temo Japaridze. Family. Oil, canvas. 118x70 cm. ATINATI Private Collection

P.S.

Temo Japaridze frequently viewed himself as a member of the “hidden generation,” a foreign caste. The "hiding" and ignoring of Temo, whether as an artist, citizen, or member of his generation (the Vera Club), was an act of punishment by Soviet officials. The artist did not conceal anything; rather, he used his talent to serve nobility. He was ardent, human... This viewpoint is vividly expressed by the statement that became the artist's credo from ‘The Silent Painting:’ “If I can expose my heart to even one person through my art, in such a manner that they don't perceive hypocrisy in me, but instead trust and pay attention to me, I will think that I have achieved the artistic realization of my personality. I hope that, with my art, I may provide at least one person with shelter, warmth, and love free of deception.”