Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Svaneti is renowned not only for its breathtaking natural landscapes but also for its unique cultural heritage. The region's rich collection of treasures encompasses both artworks of foreign origin and exceptional examples of medieval Georgian architecture and fine arts. Among the most significant and valuable pieces of Byzantine art preserved in Svaneti are the Matskhvarishi Cross and the reliquary of the Shaliani Icon of Lagurka, also known as the True Cross.

The Shaliani Icon is preserved in the most important shrine of Upper Svaneti — the Church of St. Kvirike (Lagurka). This modest, hall-type church is situated atop a mountain in the community (temi) of Kala, on the left bank of the Enguri River. Although architecturally unassuming, the church occupies a prominent place in the history of medieval Georgian art. Its interior is adorned with remarkable 12th-century frescoes attributed to the renowned royal artist Theodore. The church treasury houses exceptional examples of medieval Georgian goldsmithing, among them the Shaliani Icon, a masterpiece of Byzantine origin.

The Shaliani Icon

The origins of the Shaliani Icon in Svaneti remain uncertain. According to a local legend, a monarch of Imereti once commanded a hundred Svans to mow the fields of the Geguti Valley. Among them was a man named Shaliani, who vowed to complete the entire task alone, on the condition that he be allowed to choose his reward. After fulfilling his promise, he requested the reliquary as compensation. However, on his return journey to Svaneti, he was intercepted by residents of Kala, who murdered him and seized the icon. This legend is believed to account for both the icon’s name and its lasting association with the region.

According to another tradition, the villagers yoked two oxen to a cart bearing a log, placed the icon upon it, and released the animals to ascend the mountain as a symbolic act of divine guidance. The oxen halted at the site where the Church of St. Kvirike (Lagurka) now stands, thereby marking it as a sacred location.

The Shaliani Icon has been an object of profound veneration in Svaneti since ancient times. It is carefully wrapped in silk, stored in a locked chest, and only rarely revealed to the public. The icon is brought out on two occasions each year: on Easter Saturday and on July 28th, the feast day of St. Kvirike. On these occasions, the icon is sometimes immersed in water, a ritual based on the belief in its healing powers. This water is considered holy and is believed by the faithful to cure various ailments.

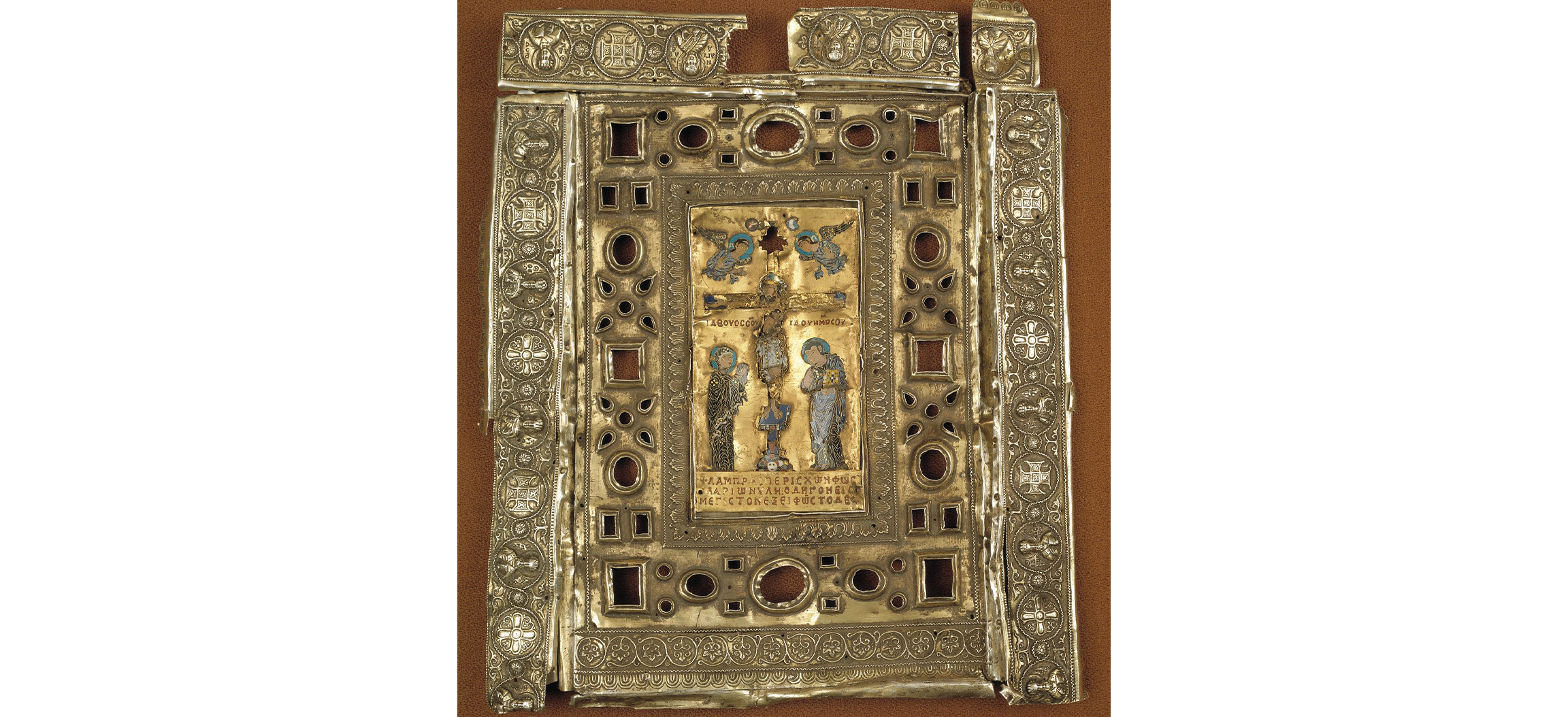

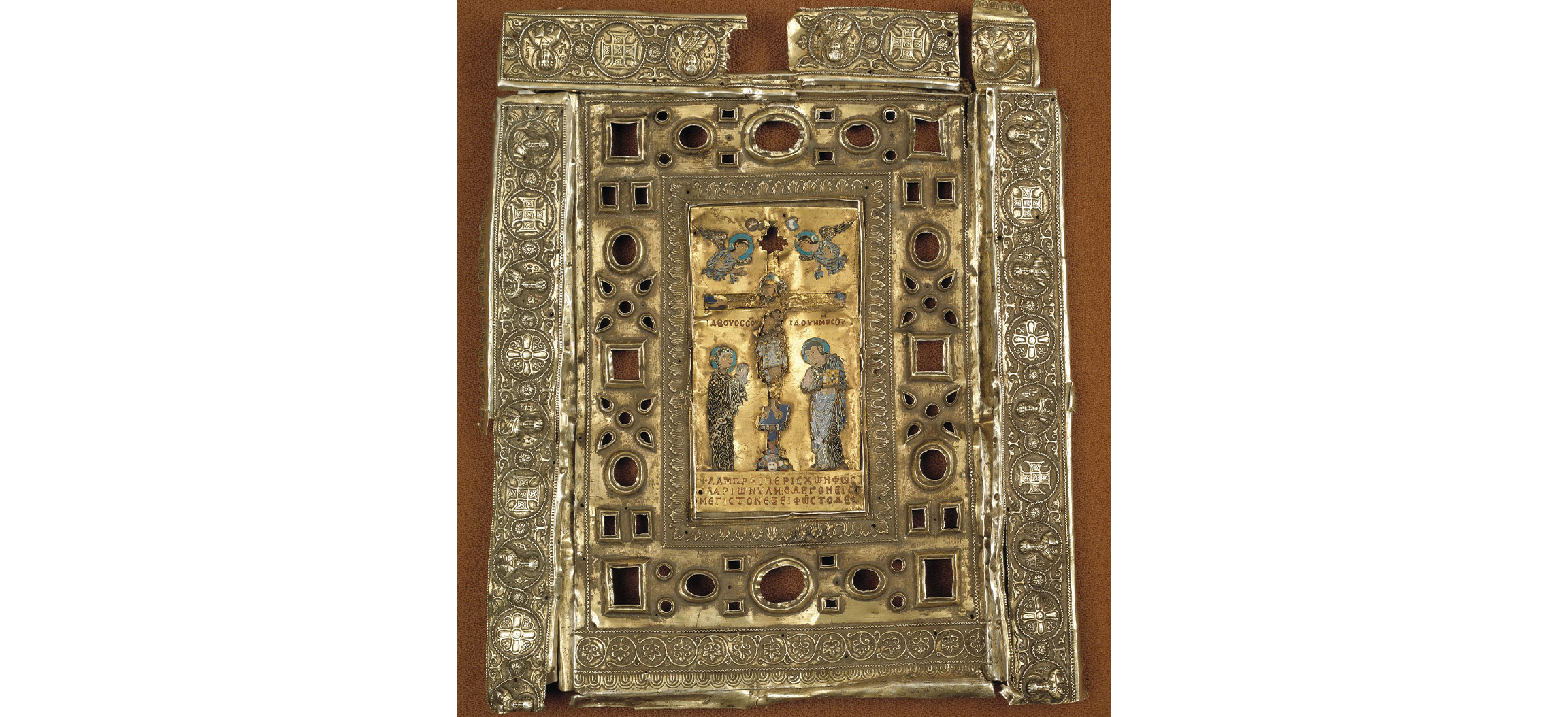

The Shaliani Icon is notable for its intricate ornamentation and exceptional craftsmanship. The decoration features repoussé work, cloisonné enamel, and semi-precious stones. Despite its damaged condition today, the icon remains a remarkable example of medieval religious art. It takes the form of a staurotheke — a type of reliquary designed to hold both sacred relics and fragments of the True Cross.

The reliquary is a rectangular wooden box (measuring 31 × 23 × 4.5 cm) covered with gilded silver plates. The upper surface features a retractable lid that conceals a recessed, six-armed compartment. At the center is a carved representation of the wooden Cross of Golgotha, arranged on four levels in symbolic reference to the Holy Cross. Four small compartments with hinged doors occupy the corners, presumably designed to contain additional relics. Each door is adorned with a relief image of a saint: St. Peter the Apostle, St. Elijah the Prophet, St. John the Baptist, and St. Paul the Apostle. Above the cross, two medallions contain half-length figures of the Archangels Michael and Gabriel. On either side of the cross are depictions of Emperor Constantine the Great — who established the Cult of the Cross — and his mother, Queen Helena, traditionally credited with rediscovering the True Cross.

The icon's movable lid is lavishly decorated. At its center is a golden plaque bearing an enamel depiction of the Crucifixion, framed by stylized acanthus leaves. This composition is enclosed within a wide arch studded with semi-precious stones, arranged in irregular "nests" that form a distinctive visual motif.

The back of the reliquary features another elaborate arch enclosing a carved scene of the Anastasis (the Descent into Hades), a symbolic representation of Christ's Resurrection and the liberation of the righteous. This scene is likewise executed in gilded silver. The side panels, similarly adorned with silver, display alternating medallions of saints in half-figure and cross-shaped forms. These are interspersed with decorative foliage and connected by multi-petaled floral motifs.

The iconographic program draws heavily on Byzantine artistic tradition. It unites themes of the Crucifixion, the Resurrection (expressed through the Descent into Hades), and Salvation — a theological synthesis commonly found in Byzantine reliquaries, though less frequently in staurothekai. One notable parallel is the 14th-century reliquary from Siena, which exhibits similar iconographic elements.

The enamel Crucifixion scene, positioned at the center of the icon’s domed lid, is among its most significant artistic features. The Mother of God and St. John the Evangelist flank the cross, while above it, half-figures of angels, along with the sun and moon, enhance the celestial symbolism. The stark, restrained color palette — blue-gray garments set against a gold background, with inscriptions in reddish-brown — intensifies the composition’s solemnity. Dark brown sardonyx stones embedded in the arches echo, reinforcing the tonal harmony of the Crucifixion scene.

A three-line iambic Greek inscription beneath the Crucifixion identifies the original patron of the reliquary: a figure named Hilarion.

The Shaliani Icon. Scene of the Crucifixion. Enamel

The cloisonné enamel adorning the Crucifixion scene on the Shaliani Icon represents one of the most exquisite examples of Byzantine enamel craftsmanship — a unified artistic solution that underpins the reliquary’s overall decorative scheme. The icon's various components exhibit some stylistic variation, but they were likely all created contemporaneously in the late 12th or early 13th century, drawing inspiration from earlier examples (the 10th and 11th centuries), as evidenced by the icon's enamel, engraving, and precious stones.

Among the most remarkable examples of medieval minor arts, the Shaliani Icon stands out for its exceptional craftsmanship, lavish decoration, and intricate detail.