Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

So it happened that Ilia Chavchavadze did not really have a home in Tbilisi until a much older age. He would always rent properties and finally got to purchase something roughly around the beginning of the twentieth century—something only a masterly architect managed to bring up to standard at the time.

This was either a former cookery, guesthouse or a rear extension to the Ghviniashvili family homestead, located on Chubinashvili Street, formerly known as Andria’s (Andrew’s) Street. It now carries the name of Giorgi Chubinashvili, intellectual founder of the art historical discipline in Georgia, who happened to be married to one of the Ghviniashvilis and is therefore a key character in the story of the unsold portion of this building.

.jpg)

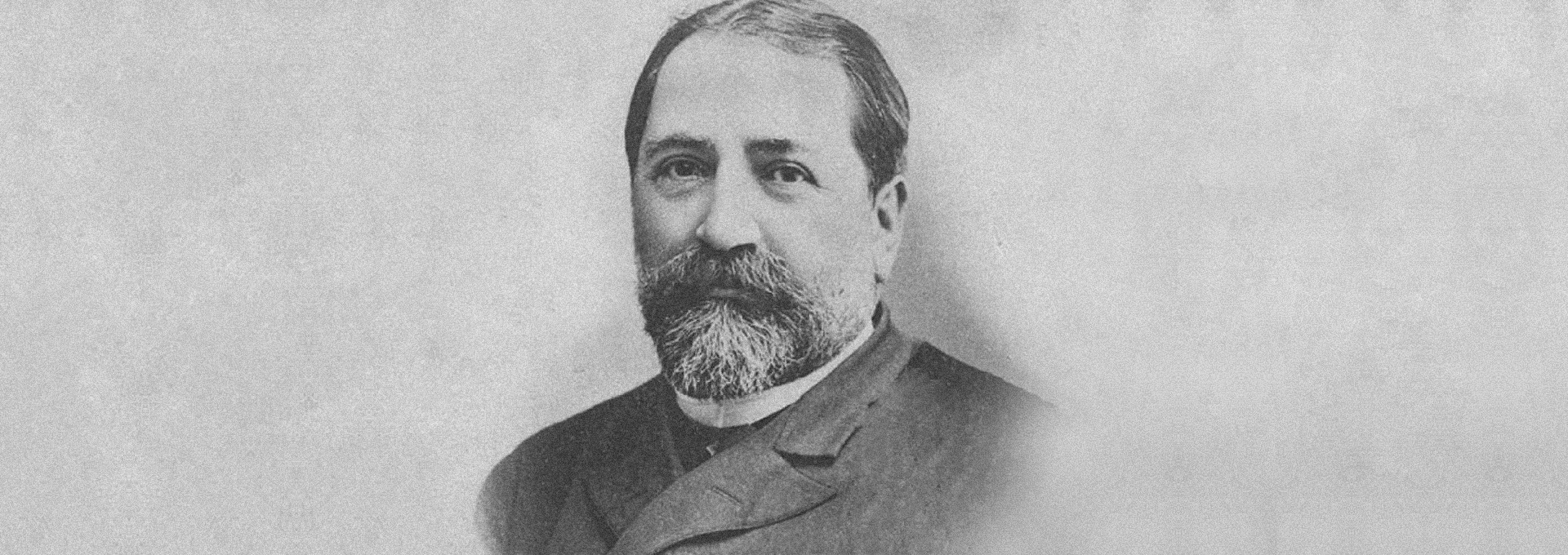

Ilia Chavchavadze - 1837 / 1907

Ilia’s property was reconstructed by architect Simon Kldiashvili, who managed to convert it into the kind of habitable space where one would easily host guests and still have a room or two for work and rest. Initially, the plan looked considerably more impressive, but as always, Ilia lacked sufficient funds to bring it into fruition and the place ended up being a lot more modest than intended. There was no need for more, he claimed. Ilia and his spouse, Olga Guramishvili, did not have any children and, at the end of the day, scale had little to no meaning for the Crownless King and his partner. He had often wished to have tried a little harder by adopting farming activities and purchasing land and buildings, but there would have been no point in doing so without an heir, he argued.

Prior to moving to Andria’s Street, Ilia spent twelve years nearby, at his sister’s, Lisa’s place on Nikolozi (Nicholas) Street, the street named in honor of Emperor Nicholas I of Russia. Georgia was part of the Russian Empire at the time, consisting of governorates of Tbilisi and Kutaisi and districts of Batumi and Sokhumi. And Emperor Nicholas, who had been to Tbilisi and even survived an accident when his carriage overturned somewhere near River Vere, present-day location of an outdoor pool, had gained a degree of immortality for the Russian administration. Therefore, they would occasionally name places after him here and there.

Lisa’s house, on the other hand, was quite big. She had inherited it from her late husband, General Alexandre Saginashvili, and resided there alone for a while after his passing, before asking Ilia and Olga to move in with her. To cut a long story short, Alexandre Saginashvili was a truly great man. Prince by descent, he came from a family of commanders. After numerous wars in Caucasus and thousands of military endeavors, he had been awarded the rank of a general and was thirty years older than his spouse, which, as an arranged marriage, was a common phenomenon at the time. But General Saginashvili, upholding his views of kinship with the Kvarelian Chavchavadze family as per longstanding customs of Georgia, stood by Ilia unconditionally throughout his public endeavors. At the time, the General had founded the Society for the Spreading of Literacy among Georgians, chaired by his brother-in-law, Ilia, for twenty-two years.

That is precisely why Ilia and Olga were well familiar with the residence of Lisa and Alexandre. In fact, every single Georgian that was keen on writing, reading, thinking and contemplating the fate of Georgia knew the address: 21 Nikolozi Street, phone number - 227.

.jpg)

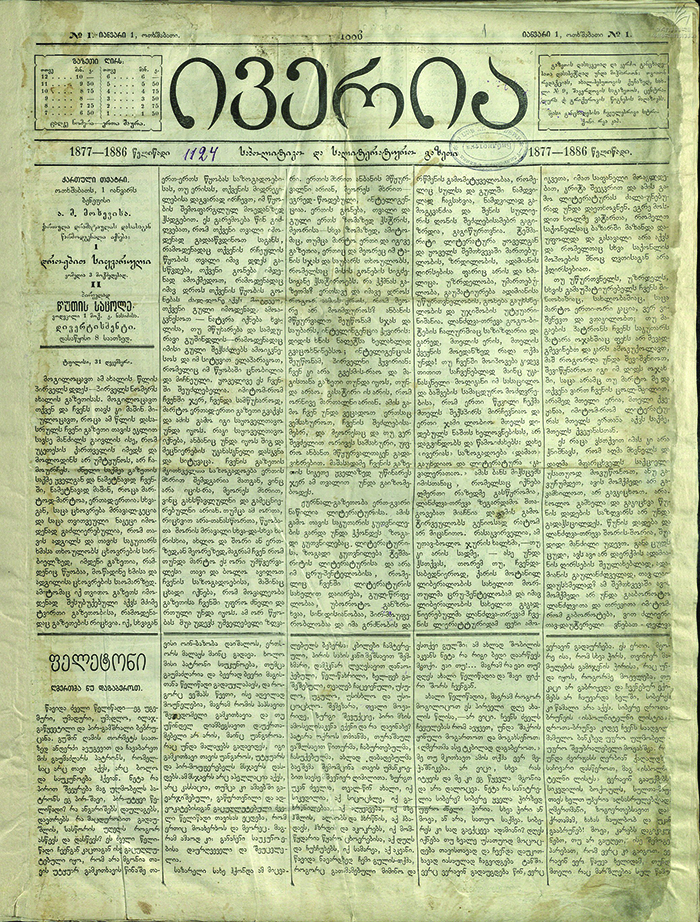

Ilia Chavchavadze on the street of Tbilisi

With the advent of telephone communication technology, a phone number was an absolute must, as the former residence of General Saginashvili had become home to the editorial office of Iveria, originally a weekly periodical that was later published on a monthly basis, preceding the telephone and enjoying enormous support of the General from conception. Moreover, the famous printing house of Maxime Sharadze was located in the basement of this building as well. Ilia Chavchvadze was the sole publisher and oftentimes editor of Iveria all along, and General Saginashvili, while still alive, thoroughly enjoyed the fact that his residence was home to an editorial office and a printing house.

The very concept of an editorial office is magical. And with Georgia being part of the Russian Empire at the time, the place had become synonymous with a hotspot of rare encounters and ideas.

Not many Georgian generals in the Russian service could really pride themselves for being such dedicated supporters of public endeavors at the time. As a matter of fact, there was not a single one that actually could, even though similar sentiments were quite common and, at that point, high-ranking military officers would certainly frequent editorial offices after resignation. Not only did they have a lot to reminisce upon, but they actually wanted to ensure that accounts of their heroism in the name of the empire would get to see the light of day. However, this was certainly not your average editorial office, and Alexandre was not an average guy either.

With the number of initiatives that Ilia was grappling with at the time, editorship of a monthly journal proved to be rather challenging. That is why he was constantly on the lookout for individuals and like-minded teams that would agree to take over the editorial office. There was a time when he would author editorials and be at the forefront of the publication, but with time, he became more of a publisher, with limited involvement in day-to-day affairs.

However, that was slightly later. And before that, terrorists from the People’s Will sacrificed themselves to assassinate Russian Emperor Alexandre II. In the words of Lev Tolstoy, as a ruler, Alexandre was both a despot and a liberal, but from the point of view of Georgia and similar lands within the Russian Empire at the time, he certainly outperformed his ancestors and descendants.

In any case, the throne was inherited by Alexandre’s son, another Alexandre— the Third. Modern-day Russians refer to him as the Peacemaker, but in reality, the principal concern during his reign was to ensure complete Russification across the empire and its adjacent territories in particular. Plus, he certainly had top-notch officials to get the job done. Natives (tuzemtsi) were placed under significant pressure.

We logically shared their fate. It was the time when General Saginashvili was still alive and Tbilisi witnessed a total and complete shutdown of publications that had maintained an open mind. Russian Obzor by Niko Nikoladze was among them. What made all the difference for Georgians was censorship and eventual termination of the only daily paper in Georgia, Droeba, founded by the late Sergei Meskhi.

That ended up being a massive setback. Perhaps, it would be tough to comprehend true essence and peculiarity of Droeba in modern-day Georgia or the world at large, but what mattered most to its editorial staff is the fact that they would get to communicate with the reader in Georgian every day, even if that meant getting a single month’s worth of pay for an entire year.

Hence, people that cared about Georgia came together to formulate a way out of this disaster: to convert Ilia’s Iveria into a daily paper.

Ilia never held back. Changes were ratified—initially, in verbal form. Gradual steps were taken, until, eventually, it was confirmed that the first issue of Iveria Daily would appear on January 1, 1886—the first day of the new year. The team got to work immediately. Daily papers require ample content and are subject to greater censorship than any other publication.

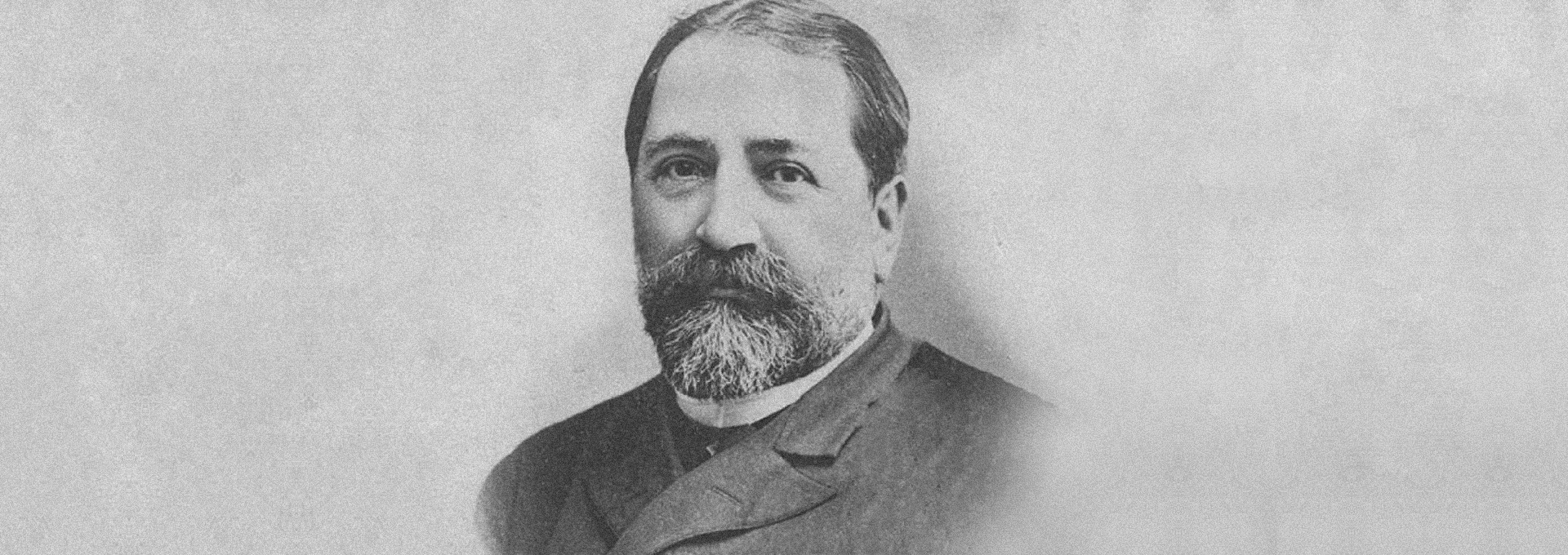

Daily Newspaper: IVERIA - January

General Saginashvili, who was fairly elderly at the time, agreed to free up a few more rooms at his residence for the editorial team. Mind you, there isn’t a single Georgian that does not celebrate New Year’s Eve with particular excitement. In the words of early writers and ethnographers, on Christmas and at the break of fast that follows, Georgians lay groundwork for the massive New Year’s Eve feast.

Naturally, the Saginashvili household was celebrating that evening. However, the party was preceded by a stress-filled workday at the editorial office. It is hard to imagine Ilia joining a feast on New Year’s Eve. He wasn’t really fond of such things—particularly anywhere other than their place in Saguramo, which Olga had brought as dowry. Here, on his name day, he was known to host a feast large enough to accommodate the entire Georgian population, but other than that, he would always try to avoid entertainment.

The table was set at dusk, bringing together close friends of the host, his relatives and, naturally, the Iveria Daily staff. The latter had been around since the morning, running back and forth with Ilia.

Daily grind in the newsroom continued all through the night.

Ilia Chavchavadze being a guest

Prince Raphael (Raphiel) Eristavi, the poet, was the toastmaster for the evening. The strange feud of imperial days eventually led to Raphael becoming a censor of the written word in the Tbilisi Governorate i.e. half of Georgia at the time—that same person who once authored one of the most soul-stirring and Russian censorship-free poems about the motherland: “The lives of men are swayed by love for one God and one motherland… Not for all the trees in Eden would I these rugged cliffs exchange, nor for paradise undreamed of would I my native land exchange!”

Such were the days—two-faced and duplicitous. But Iveria was loyal to its cause and, while the joyous feast upstairs went on, Maxime Sharadze and his boys were putting together the first issue of the daily paper downstairs. Typesetters were being supplied with ample food and wine from above. Half of the time, Ilia was in the basement as well, and within moments of the New Year hour, the first two sheets of Iveria Daily arrived.

Ilia Chavchavadze on the street of Tbilisi

Those who remember the scent of ink and paper from that printing house will easily relate with the sensation.

It was a genuinely Georgian scene: the feast and those fragrant scents from the printing house. These newspaper pages, hot off the press, were being passed from hand to hand. Kissed and revered in the process, once these sheets reached the toastmaster, Raphael demanded benediction of the paper as per Kartvelian customs. At the time, drinking vessels were not referred to as “Ganskhvavebuli” (literally: special, different), but certainly stood out by volume.

As Raphael had requested something substantial, Lisa and Olga located an old silver chalice at their house. The feasters placed a couple of fresh pages of the paper into the chalice and poured wine on top. That is how they drank a toast to Iveria.

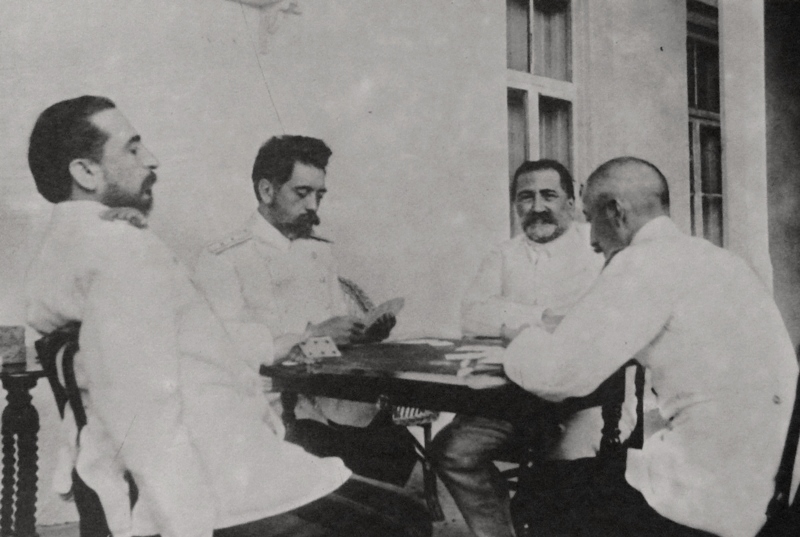

Ilia Chavchavadze playing cards

Such were the days: warm pages of Iveria, chilled with wine, stood for a new beginning. In fact, that ended up lasting quite a while: Iveria signified vital signs of a humiliated, tormented Georgia. And with Kakhetian wine and a silver chalice as attributes for its benediction, that certainly comes as no surprise.

Jokes aside, Iveria lasted twenty more years after that. It ended up being shut down more than once, but somehow kept rising from the ashes. A year after its full termination, Ilia was murdered by leftist terrorists. In the popular words at the time, they would have murdered Georgia as well, had that been an option. And Iveria certainly was not the highest-circulation paper at the time. On the other hand, it was passed from one hand to another: that certainly comes as no surprise, considering the fact that it carried stories about Georgia, written in Georgian—a Kartvelian language.

Literary translation by Mziko Lapiashvili