Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

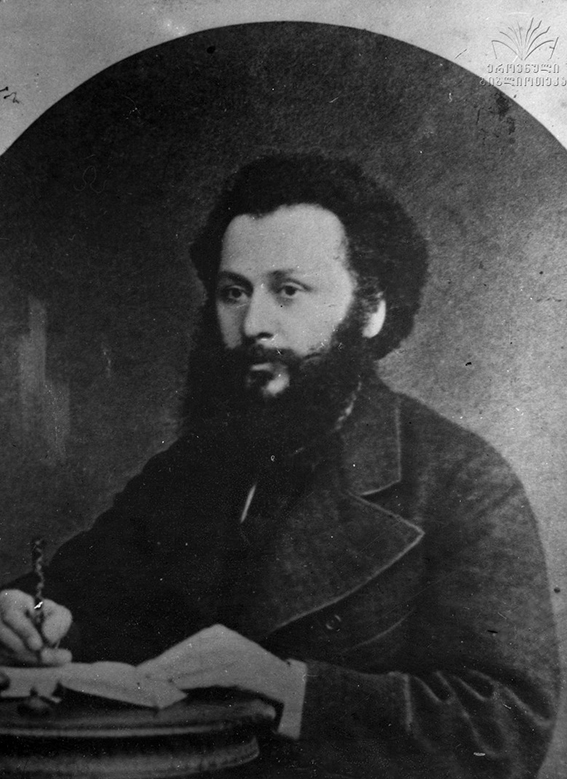

The Georgian writers of old times had different working conditions. Of course, some of them were very rich, like the General and poet Grigol Orbeliani were very rich, some of them belonged to the middle-class, while others, like Vazha-Pshavela were quite poor and only survived thanks to their peasant work or as one would say in those times, “operated the hoe”, were quite poor.

Grigol Orbeliani - Georgian Romanticist poet and one of the most colorful figures in 19th-century Georgian culture. (1804/1883)

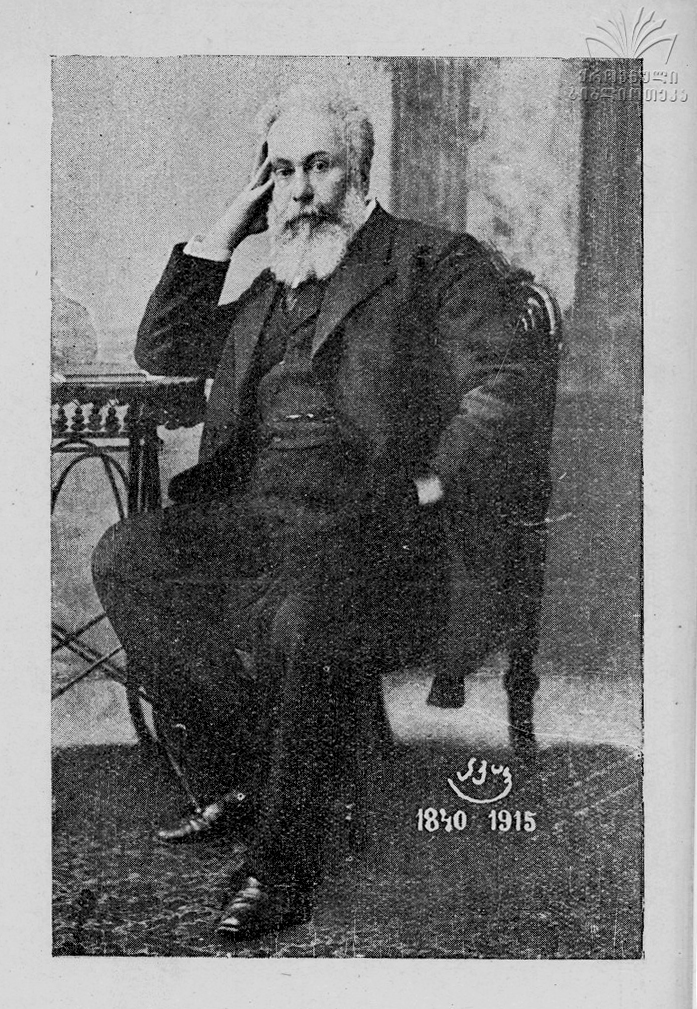

Akaki Tsereteli was the only writer who supported himself with literature or related activities. During his long life, he was only briefly and very rarely engaged in public projects. For example, at the times when he acted as a head of a theater, he would quickly write the plays for its repertoire, collect the folklore pieces, publish the “collections” of private texts and folk poems, and so on. He really remained the only individual who tried to survive in the vast Russian Empire by writing his poems and stories in the Georgian language. However, he never managed to secure an income, which would have enabled him to become carefree author.

Akaki Tsereteli – Georgian poet and national liberation movement figure (1840/1915)

Akaki was well known for his vagabond lifestyle: despite the fact that he was the offspring of a robust noble family and had inherited the wonderful house of his ancestors in the village of Skhvitori, Imereti region, the poet considered the place as a resort rather than a latifundium that could be of some use. When being on travel away from Skhvitori on his travels, Akaki used to stay at the hotels and at his friends’ houses maintaining this habit for many years.

Akaki TSereteli – Georgian poet and national liberation movement figure (1840/1915)

Akaki advised young writers not to take on any jobs if this was not prompted by an absolute necessity, and if accepting an employment proved to be unavoidable, never to work for a state institution. In his opinion, any kind of work had a negative impact on literary activities, especially if it was related to a state service.

These were the times when the most authors who were his contemporaries survived thanks to working for state agencies, which allowed them to enjoy the benefits of a regular income. This indeed occurred in the cases of popular publicist and writer Anton Purtseladze, the marvelous poet Rafiel Eristavi, King of Tbilisi's bohemia – the playwright and actor Akvsenti Tsagareli, and the others.

The correctness of Akaki’s approach became apparent in the example of Tsagareli who at the age of 23 or 24 had already achieved significant popularity. His plays Khanuma and the Other Times Now were not only staged at the professional theatres, but were also performed by amateur theatre collectives in every corner of the larger and smaller cities of the South Caucasus. Nonetheless, it very soon became clear that Tsagareli and his wife Nato Gabunia, at that time a star of the Georgian theatre, were not able to survive on the income generated from writing plays and acting, and Tsagareli was forced to find a job. He was subsequently appointed as head of a small Transcaucasian Railroad station - a position that secured his salary for many years, but which deprived him of the opportunity to write any more plays.

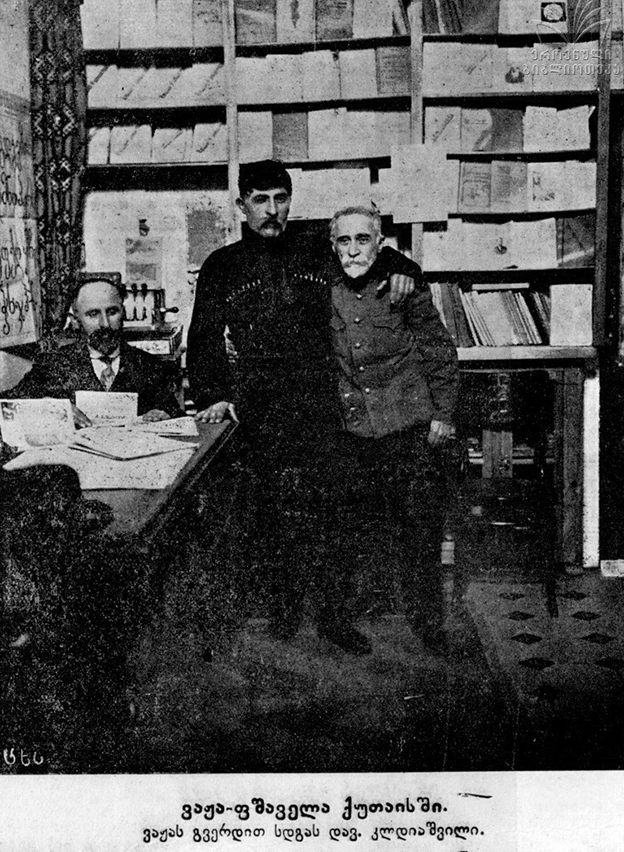

Vazha-Pshavela, is the pen name of the Georgian poet and writer Luka Razikashvili (1861/1915) with David Kldiashvili was a Georgian prose-writer (1862/1931)

Others employed different methods to buy time for writing. Vazha-Pshavela’s children, relatives and friends recall that he always carried a little pencil and various scraps of folded paper in his pocket. It did not matter if he was working in a field, on a hunting trip or doing something else: he would immediately abandon any activity to sit and write down his thoughts. It made absolutely no sense to approach him at that moment, since he totally distanced himself from the field work, hunting, collecting water or engaging himself in anything else. At home his evenings were reserved for work, which he produced sitting at a small table in a cramped corner under the light of a traditional oil lamp from the Pshavi region. This was the best part of the day for him to immersive himself in his creative endeavors.

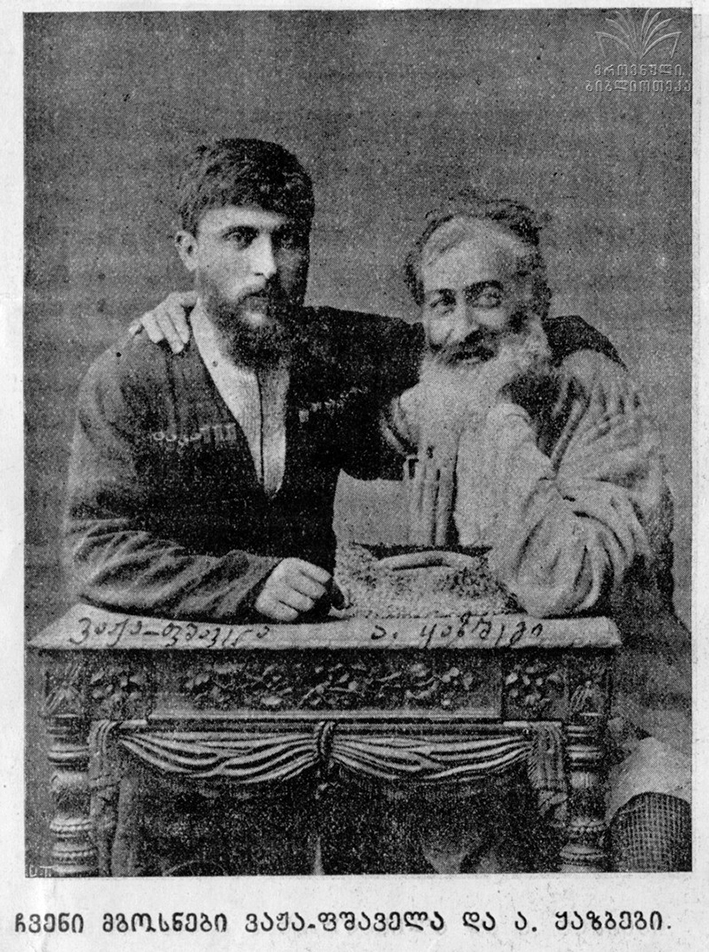

Vazha-Pshavela, is the pen name of the Georgian poet and writer Luka Razikashvili (1861/1915) with Alexander Kazbegi was a Georgian writer(1848/1890)

For Alexandre Kazbegi there was no difference between day and a night. There were times when he literally lived in the editorial office of the magazine Droeba while writing the novels on large sheets of paper and publishing them in the following issue. Engrossed in the creative process, he took no notice of the surrounding world; he was entirely focused on his writings and the emerging emotions. Kazbegi wrote in large, interlaced letters owing to his poor eyesight and a stubborn reluctance to wear glasses.

Akaki wrote everywhere that he could find a table. Since his frequent trips meant that he would spend entire months at his friend's houses, his hosts usually placed a small table in his bedroom. The same happened at his parents’ house n Skhvitori: he had no need for a separate study as he could work in his bedroom. Akaki preferred to arrange uninterrupted writing sessions and finish a piece in only one go. He would only split his work up into several sessions while working on larger stories, when he needed to stretch his work over the course of several days and had to sleep in between. Speed was also a necessary attribute of his working process. Two months prior to his death, before becoming bedridden and being brought back to Skhvitori by Kote Abdushelishvili, Akaki traveled to Kutaisi seek money there. It was a freezing, snowy winter. Being unable to afford a room with a fireplace, the old poet stayed at a hotel where he occupied an unheated room. After unsuccessful attempts to borrow money, he decided to use the room for work and quickly wrote a poem to sell.

Ilia Chavchavadze was a Georgian public figure, journalist, publisher, writer and poet who played a major role in the creation of Georgian civil society (1837/1907)

Everyone had their own style of writing, but Ilia Chavchavadze was the one who had not only the most organized working space, but also probably the most organized character and approach. He perceived writing as a huge responsibility – a notion he followed from a young age. He was a writer and poet, but also routinely worked as a publicist and was engaged in a newspaper job that demanded he maintain a clear head and precise ideas. Accordingly, his texts very rarely include flaws, exhalations, distractions, or so-called “hackworks”. His employment at a magazine, followed by a position at the weekly and later daily newspaper Iveria, demanded his undivided attention. At that time Ilia already had extensive prior experience of editorial work at the magazine Sakartvelos Moambe (Georgian Newsletter) and was always on the hunt for a good word and a correct sentence.

If we also consider the fact that Chavchavadze was a chairman of the Bank of Nobility and the Society for the Spreading of Literacy among Georgians, and served as a mediator with the Imperial authorities for all small and large scale Georgian businesses, it becomes clear that all of this could not have been achieved without outstanding self-discipline.

_სიტყვას_წარმოთქვამს.jpg)

Ilia Chavchavadze (1837/1907) during the speech

For Chavchavadze the order of words, i.e. “correct Georgian” constituted half the job. According to the staff members of Iveria, he used to repeat a saying in reference to newly submitted essays or articles from regular well-known authors. Ilia would summon one of his colleagues and tell him: “Come, let’s taste this writing.” The phrase did not concern the ideology or opinions of the author; it only referred to the style of writing. Ilia had a good sense for a correct, while not yet officially established but up-to-date Georgian, and also understood well the language of common people. He maintained the same and perhaps even stricter approach with respect to his own writing. The publisher and editor of the daily newspaper gave his articles to the staff members for review, and demanded that they use a red pencil for corrections.

Decades of intensive daily writing were followed by periods when Ilia worked on large stories and essays. According to his biographers, this work could have taken an entire month. After having established the editorial office at his home, Ilia opted to work in his study.

This was a renowned place where the walls were decorated with photos of the European landscapes; the corner housed a comfortable table and a low couch that could have become a favorite piece of furniture for any Georgian... The room was filled with many other objects too. In short, when Ilia decided to write, this was the place he took refuge to.

Although this isolation did not necessarily mean turning the key in the keyhole, the process nevertheless precluded the possibility of the newspaper staff entering the room. “Ilia works” meant that the doors of his study were open only to his wife Olga, who was twice a day allowed to bring in tea and leftovers from lunch.

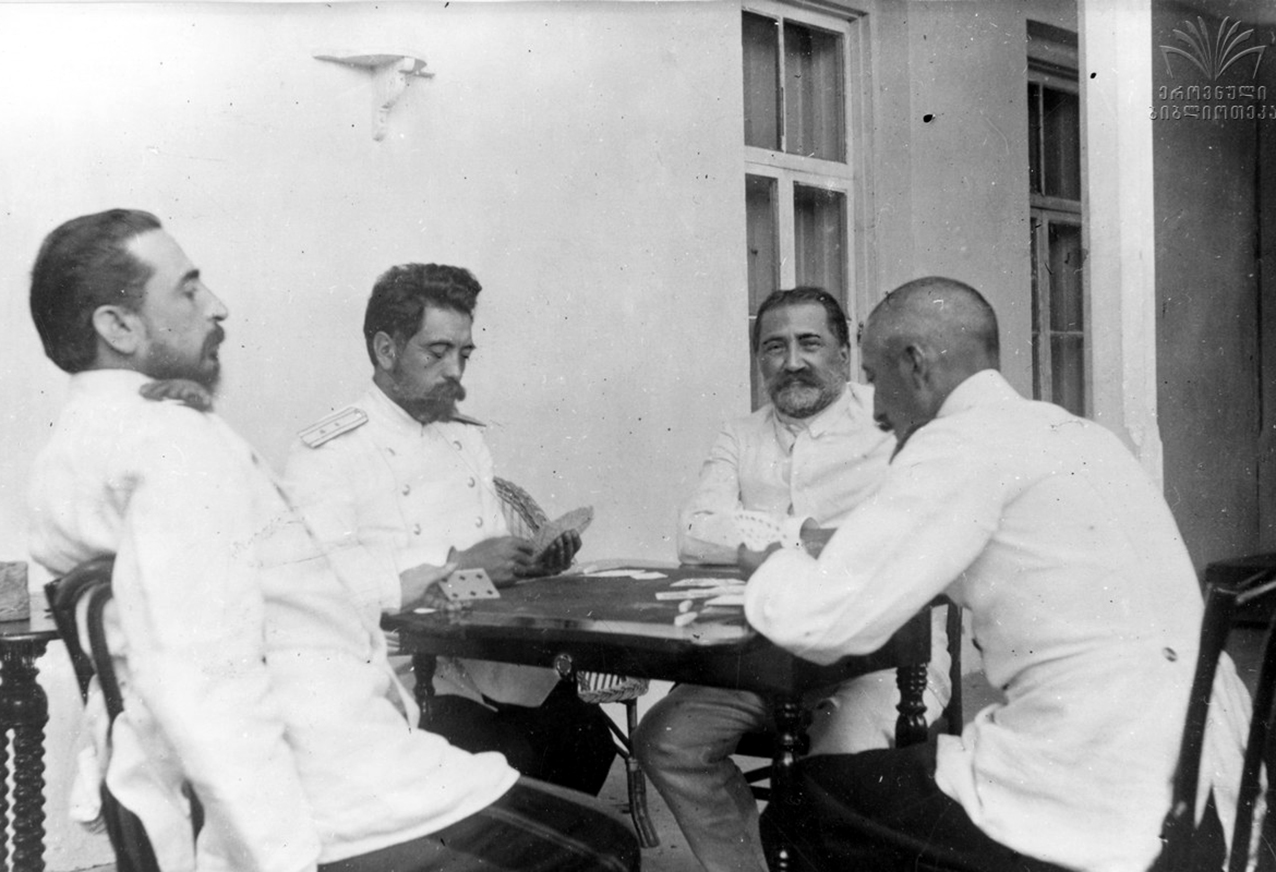

Ilia Chavchavadze playing cards

Ilia did not pay attention to who came in in and out of his room; he knew that it could only be Olga. He did not say thank you for the tea, and ignored all events happening around him. The chain smoker’s room was filled with smog that resembled the atmosphere in London at that time- filled as it was with factory fumes. In his recollections, Artem Akhnazarov refers to it as a huge cloud of smog. Ilia’s round-the-clock work was interrupted only by the irregular naps that he took on the famous sofa at any tine of the day of night.

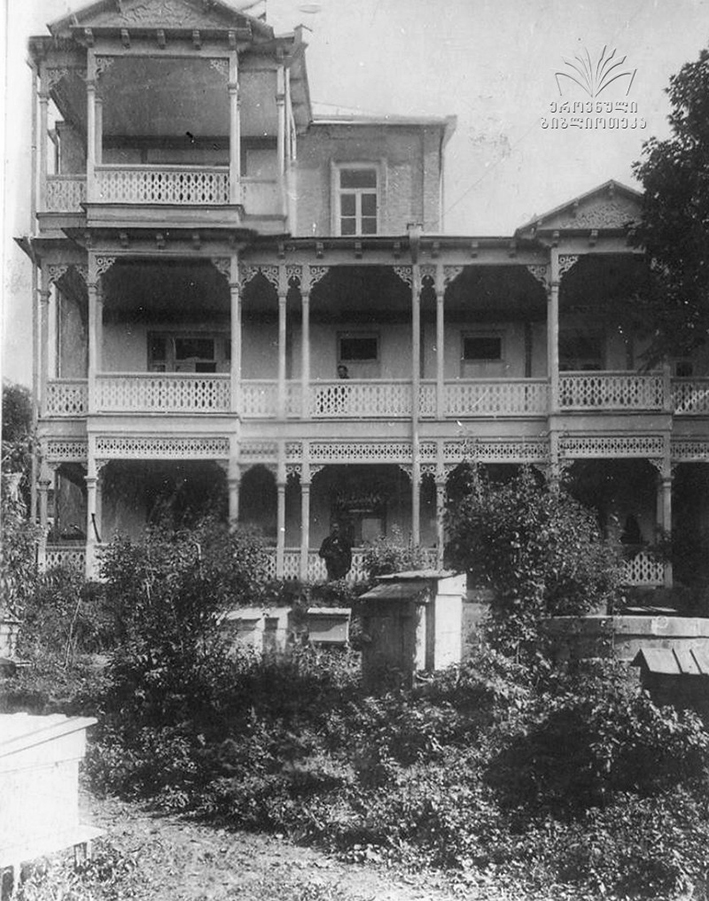

House of Ilia Chavchavadze in Saguramo

The processing of the texts was of significant importance to him, and according to the eyewitnesses could turn into a continuous job that lasted for a whole month. These periods were disencumbered from phone calls, invitations, or any other distractions. Even Ilia’s famous Thursday dinners were cancelled during such times.

Finally, after having completed the work, Ilia dived right back into the joys of life: dressed casually in an evening gown and with an Ottoman fez on his head, he would lay down on the couch in his study and smoke for a pleasure rather than out of habit, and at the same time be joyfully engaged in conversation with anyone who entered the room.

Ilia Chavchavadze's working table

A couple of days of leisure were followed by the “tasting” of a new piece. The staff of the editorial office read the text individually and marked it with notes written in red pencil. Notwithstanding the comments and corrections, Ilia was happy at the opportunity of having shared his ideas.

In short, everyone has their own habit of writing.