Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

The story of Parnavaz (299-234 B.C.) begins with a legend about the military expedition of Alexander the Great in Iberia (eastern Georgia or Kartli). Alexander conquered all the lands of the known world, and during his glorious conquests he also visited Iberia. Here, in Iberia, he came across strange people with bizarre and disgusting habits. Who were these people? Medieval Georgian authors called them Bun-Turks. There is much discussion about what this ethnonym means. Presumably the first part of the word, Bun, could be understood as ‘original’ or ‘first.’ It is hard to say why the Medieval Georgian authors thought that they were Turks. Whoever they were, according to Medieval Georgian accounts, abomination was their lifestyle. They did not recognize blood relations, and fornicated with each other indiscriminately. They ate everything and feasted on their dead. Upon his first arrival, Alexander was unable to banish them. However, he later grew stronger, and invaded this land again. This time he attacked the castle of Sarkine (near Mtskheta; it literally means ‘the place where iron can be found’), which was where Bun-Turks were enclosured. After several months of besiegement, the Bun-Turks drilled a hole in the castle wall and managed to escape. Alexander conquered the whole of Iberia, slaughtered the foreign tribes, and took many hostages. The legend narrates that he spared the Georgians (this clearly shows that Georgian medieval tradition was positively predisposed towards Alexander). As he was leaving Georgia, he appointed a certain man named Azo (‘his relative,’ as one of the Georgian chronicles announces) as the ruler of Iberia. Azo was from ‘Arian-Kartli’ (this term denotes the Georgian lands that belonged to the ‘Arian’ or Iranians, i.e. Achaemenid Persia as we know from the accounts of Herodotus).

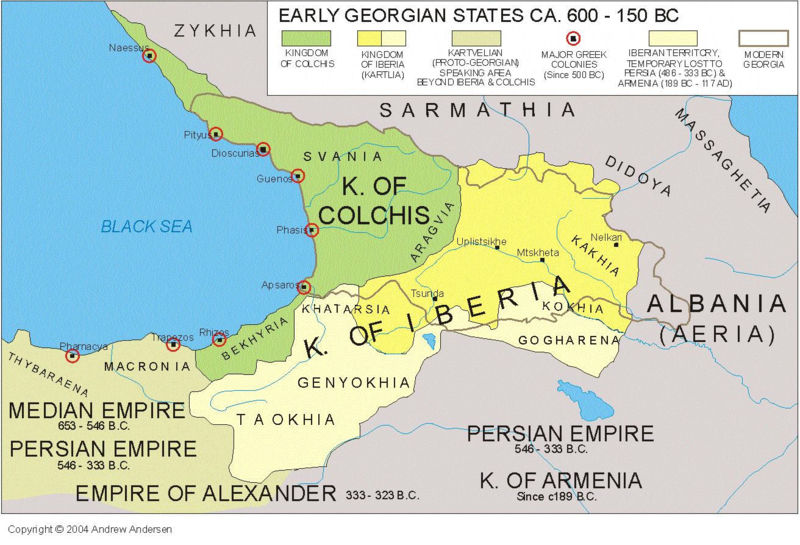

Kingdom of Ibera

Azo became ruler of Iberia. He established himself in Mtskheta, and had many castles and fortresses built. Azo proved himself to be a cruel tyrant. He slaughtered Samara – the head of the local Mtskhetian community, a house that governed the central lands of Kartli – and began a bloody oppression of all who opposed him. In Mtskheta he erected idols of Gats and Gaim – ancient and mysterious gods of old. He ordered that any Georgian who would take up arms should be slaughtered. Azo persecuted everyone who still maintained loyalty to the house of Samara. However, Azo did not kill everyone from the ruling house of Mtskheta. Its lineage survived and grew in strength during the subsequent years.

The legend about a young warrior who survived the fall of the ancient house of Mtskheta lived on. This legend inspired Georgians for centuries. It is the tale of Parnavazi – a nephew of Samara – who reclaimed his ancestral seat and, furthermore, went on to become the first King of Iberia. This legend in its final form has been preserved in a major medieval Georgian chronicle known as The Life of Georgia. Of course, the story is steeped in mythology, but there is also a great deal of historical truth to it.

Royal hall in Mtkheta

The Legend tells us that after Samara had been murdered and his house destroyed, the young Parnavaz fled with his mother to the northern Caucasus. The future king grew up among the impregnable Caucasian mountains and strongholds. Parnavaz longed for revenge. He never forgot what the foreign invader and pretender Azo had committed against his family and country. As he grew up, he became an excellent fighter and hunter. Stories about his feats reached Azo, who duly summoned the young warrior to his court. Parnavaz proved that the stories about his valor were no lies. Azo became very close to the young man, but this was a very dangerous path, and Parnavaz’s mother warned her son of Azo’s jealous and low cunning character. Parnavaz also feared that he might expose himself. He was not so much afraid for himself as for his mother and kin, since in the event of Azo learning his real identity, they could not escape painful death.

One night Parnavaz had a dream. He was in complete darkness and feeling utterly helpless. Suddenly a light appeared. The sun’s rays pierced through the darkness and took him out of the realm of darkness. Parnavaz stood before the dazzling light. Stretching out his hand, he cleansed the sun with the morning dew, and then anointed himself with it. Never before or after in his lifetime did Parnavaz feel such joy and relief. After this dream, Parnavaz regained his courage. He took up his ax and his bow and arrows, and went hunting in the forest. Within a short while he came across a female deer and shot an arrow at it. The deer was wounded, but she ran away. Parnavaz chased her, but the deer fell from a cliff. Parnavaz descended the cliff and sat beside his prey. The sun was going down, and soon gray clouds obscured the sunlight. Parnavaz felt drops of rain on his heated face. It began to rain more heavily. He looked around for a place to shelter from the rain, and caught sight of the entrance to a cave that was blocked with huge stones. He climbed the slope and approached the cave mouth. He took his ax and broke the stones that blocked his way. It was dark inside the cave, but here the young prince found a trunk full of golden jewelry, coins and chalices. Parnavaz blocked the entrance again, and returned home to tell his mother and two sisters about the treasure. They gathered the treasure and hid it in a safer place.

Afterwards Parnavaz sent his servant to Kuji, who was the renowned lord of Egrisi in western Georgia. Parnavaz persuaded Kuji to fight together with him against Azo. Kuji rejoiced because now he had the chance to eliminate such a dangerous and powerful neighbor as Azo. Kuji told Parnavaz that not only Georgians, but even many of Azo’s own servants were willing to join them. Kuji summoned his men and joined Parnavaz’s cause. Parnavaz and Kuji also sent envoys to the Caucasian highlander clans, who joined the rebellion as well.

However, most important was the assistance that Parnavaz received from Seleucid Persia. Parnavaz knew that even if he became a powerful ruler, there were other more powerful and dangerous rulers out there. One of them was Antiochos I Soter (‘the Saviour’), (281–261 B.C.) who had occupied his father’s throne – the seat of Seleucus I Nicator (305-281), a general who had fought alongside Alexander the Great. Antiochos sent Parnavaz a precious crown and proclaimed Parnavaz his son. The young Parnavaz had everything in his hands to begin a war against the usurper. And so the rebellion began. Azo was furious. He summoned his troops, but before they even met the rebels on the battlefield, a thousand of Azo’s cavalrymen had deserted and joined the rebels. Azo did not feel safe in Mtskheta. He escaped to the south-western province of Iberia – Klarjeti. Parnavaz attacked the remaining troops of Azo. One after another, Parnavaz besieged and captured four castles around Mtskheta and then triumphantly entered the city of Mtskheta itself – the seat of his fore-fathers. In the space of one year, Parnavaz conquered almost the whole of Iberia. For their part, Kuji and the northern Caucasian chieftains secured the support of western Georgia and the northern Caucasian clans. Once he felt that his rule in Mtskheta was safe, Parnavaz marched once more against Azo. Azo was defeated and murdered in Klarjeti. Now Iberia was entirely united under Parnavaz’s rule.

The Six-column hall in the Royal neighborhood of Mtskheta

The reign of Parnavaz was long and glorious. The founder of the Iberian kingdom carried out major reforms that were necessary for effective rule. Firstly, Parnavaz united not only Iberia, but both eastern and western Georgia. He decided how to manage this vast territory, dividing it into several administrative entities. He appointed eight eristavis or rulers for the eight different districts, and one spaspeti or general administrator for the central province of Iberia. Eristavi was a Georgian office of local ruler that traditionally represented the King in local Iberian communities. Literally it means ‘the head of the people’ (‘eri’ – people, ‘tavi’ – head), while spaspeti referred to a Persian military office (‘spahbed’). The holder of this office was paramount lord and second-in-command after the King of Iberia. Naturally, we do not actually know if the office of Georgian eristavi derives from that ancient period, but it certainly has its roots in pre-Christian Georgia.

Parnavaz’s authority spread beyond the Kingdom of Iberia. He established his political domain across the icy mountains of Caucasus. He married one of his sisters to the northern Caucasian chieftain who had helped him during the rebellion, while another sister he gave to Kuji – his old and loyal friend. He strengthened his alliance with the northern Caucasian tribesmen and western Georgia. He restored all of the ruined castles and cities in Iberia that had been destroyed during those turbulent times, and fortified them again.

Parnavaz also implemented important religious reforms. He erected an idol called Armazi, who represented a mighty and powerful god of pagan Georgia. For many years scholars believed that Armazi was a local Georgian version of the Persian god Ahura Mazda. However, in all probability it is a remnant of the ancient Hittite moon-god Armathat, which had survived in Georgian pagan religion. Parnavaz did not destroy the idols that had been erected by Azo before him; instead he chose to erect the idol of Armazi between the two statues. Armazi was made of copper and clad in golden ring mail. His eyes were made from precious stones that blazed at the worshipers, and in his hands he held a sword as symbol of his power and authority.

Ruins of the pagan tempe in Mtskheta

Besides these administrative and religious reforms, The Life of Georgia ascribes the introduction of the Georgian alphabet to Parnavaz. Scholars know little about the Georgian alphabet before Christianity. Archeological materials do not confirm that the Georgian alphabet existed before the country’s Christianization. However, some scholars assume that pre-Christian Georgians employed Aramaic script as their writing system.

The wine-house in the royal neighborhood of Mtskheta

In the words of The Life of Georgia, Parnavaz ‘became king at the age of twenty-seven, and reigned happily for sixty-five years.’ He was subject to Antiochos, King of Asurastan. All the days that he was seated (on the throne) passed in peace; and he made K'art'li prosperous and rich… and everyone would say: ‘We bless our fortune because it brought us a king from the line of our fathers, and removed from us the tribute and oppression of foreign nations.’ All of this Parnavaz accomplished through his wisdom and benevolence, valor and grandeur.’ After a long and glorious reign, King Parnavaz died and was buried beneath the idol of Armazi.