Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

The only employment for which Pirosmani ever received payment was at the Transcaucasian Railway. At all other times and occasions, he never worked for remuneration, and consequently, never enjoyed any social security benefits. Together with his friends from Kizikhi he operated a small shop on the edge of the Vera district, and worked on numerous art commissions for which he received an income. But his only salary and state employment was related to the railway.

Why did he decide to become a railroad worker? We do not have a precise answer to this question. It is presumed that he did it in order to find some peace of mind and save a little money.

It would have been interesting to see him dressed in the uniform of a railroad worker; however, such a photo has not survived.

At that time in the 19th century, a job at the Transcaucasian Railway offered salvation in terms of income. It was a secure and comfortable position that enabled one to support oneself. The growing and restless Transcaucasian Railroad employed Georgian writers and journalists in simple and other not so simple posts for decades.

Beerhouse "Zakatala". 92x120. Oilcloth, oil. Photo credit: Catalogue "PIROSMANI" second edition 2019. Georgian National Museum

Nikala served there for more than three years. His position was referred to as “the brake conductor of freightliners.” He was first hired as an employee of Khashuri and then Mikhailovo station, later being moved to Ganja, aka Elisavetpolis.

The position of brake conductor was one of the lowest paid on the Russian railway, but as the Transcaucasian Railroad was a well-functioning, large-scale institution, this job was a very desirable one.

The work of a brake conductor was apparently simple, but actually quite difficult. The conductor had to stand on the back platform of the carriage and wait for the signal of the main conductor to pull on the carriage brake and contribute to stopping the train. The brake conductor had to stand on the platform and remain vigilant for hours. The job had to be done in any season and notwithstanding any weather conditions.

When Pirosmani decided to serve this profession, he was issued a uniform, a coat, a peaked cap, a balaclava hat, boots, and everything else required for the position.

It is no surprise that it soon became obvious the job was intolerable for a man of Pirosmani’s nature. It was both tedious and limited his freedom. Apart from the salary, his only interest would be linked to free travel.

Young fisherman. 46x73. Cardboard, oil. Photo credit: Catalogue "PIROSMANI" second edition 2019. Georgian National Museum

Pirosmani was hired by the railway company in April 1890, when he signed a document confirming that he had become familiar with the regulations and would be willing to pay fines in the event of their violation. He accumulated a lot of penalties.

The railway archives preserved his entire official relationship with the officials of the Elisavetpolis Station.

It is hard to imagine that Pirosmani was an exemplary worker, since by that time he was already interested in nothing more than painting.

A year after having begun working for the railroad, he addressed the head of the transportation department with a request to find him a place to live in Elisavetpolis. However, this request was the second in a row after having previously asked the administration to relocate him to Tbilisi where his elderly parents lived, so that he could receive his inheritance.

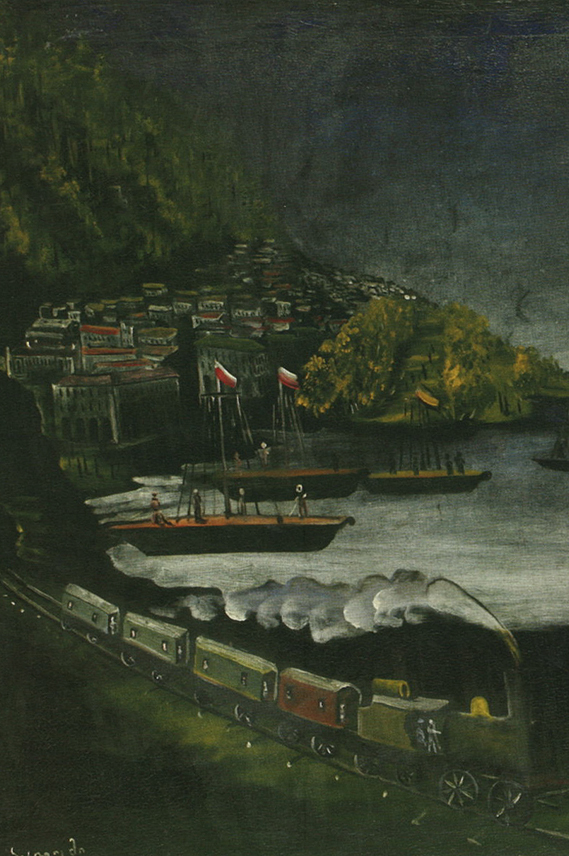

Batumi. 92x117. Oilcloth,oil. Photo credit: Catalogue "PIROSMANI" second edition 2019. Georgian National Museum

Of course, Pirosmani neither had elderly parents nor was eligible for any inheritance. He just wanted to go to Tbilisi, which for him was associated with the location of a creative practice. Most probably he knew that the railway company would not cover his living expenses, and merely hoped it would accommodate his principal request.

The following year was that of an epic battle over absences and medical treatments. The Railway issued Pirosmani fines more frequently than it fulfilled his requests. It is difficult to say that its staff member was treated with premeditated strictness. It is simply hard to imagine his requests being fulfilled, given the nature of the service. Russian railway companies had never experienced such a capricious and enigmatic brake conductor as a staff member.

Nikala's communication with his superiors took on the form of a kind of struggle to obtain days off. For example, in one of the request letters he cites family problems, and asks for two days off and a train ticket to Tbilisi. Yet he has no family! He just wants to go to Tbilisi.

He later asks to be transferred to work in Tbilisi, citing his illness as the reason. In the spring of 1892, Pirosmani submitted several requests to his superiors. He wrote that he suffered from rheumatism, complained of severe pains in his chest, and quoted the opinions of private or state doctors that the only appropriate treatment for his condition would be available at the sulfur baths of Tbilisi.

Tbilisi! Tbilisi once again!

Tbilisi Funicular. 112x90. Oilcloth, oil. Photo credit: Catalogue "PIROSMANI" second edition 2019. Georgian National Museum

A few days before filing this request, he asked for one month’s leave in exchange for two years of service. It is clear that he was bored and tired of his job. He also visits a doctor in Elisavetpolis to obtain a diagnosis for his health issues, stating that the local doctors are not able to treat him. From this point on he attempts to free himself from the railway owing to illness, and even tries to receive a little compensation in exchange for his shaken health.

The railway company believes that Pirosmani, with his constant complaints, arbitrariness and illness serve as a bad example to the other employees. The director receives a letter that recommends letting him go.

He is considered to be an unfit and disobedient staff member who is frequently fined. There are several more issues to note: he transports passengers in cargo trains without permission; he does not obey orders that he considers to be unjust and not relevant to his position, and is frequently absent from work – mainly as a result of the common cold that he blames on the working conditions. According to a document written in the name of the manager, it is difficult to communicate with Pirosmani. A clerk notes that he speaks even worse than he writes.

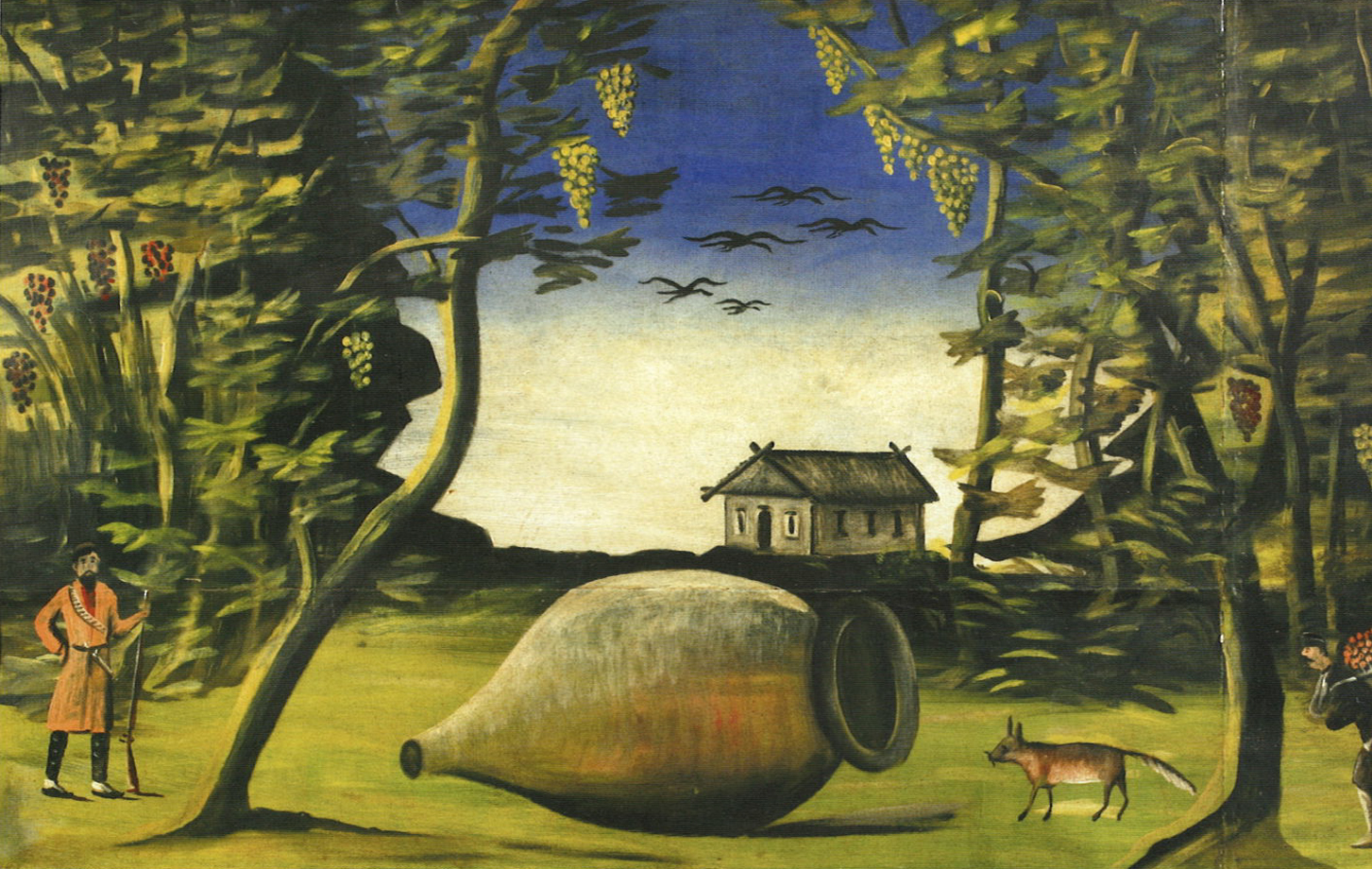

Big marani in the forest. 100x170. Tinplate, oil. Photo credit: Catalogue "PIROSMANI" second edition 2019. Georgian National Museum

It has never been a secret. Pirosmani is an emotional person, and any discussions or unnecessary explanations, specifically interrogations, turn into a burden for him.

Despite his demands to be made redundant and awarded the benefit payments of a railroad worker with health issues, he is subject to penalties.

By the end of 1893, Pirosmani stops working, temporarily returns to Tbilisi and upon his arrival in Elisavetpolis, packs his scanty belongings and abandons the life of a brake conductor forever.

From that time on, he works only as a painter.