Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Natela Iankoshvili was an artist entirely absorbed in her creative work. Her paintings represent different stages in her life. She didn’t have a child of her own, and considered her paintings her children. In each of Iankoshvili's works, be it a portrait, a landscape, an easel graphic, or an illustration for a book, the artist's stubborn, bold, firm, and complex character seems fully embodied. Her husband, the writer Lado Avaliani, who studied with Natela Iankoshvili at the Tbilisi Art Academy, believed that her art carried existential importance for her. As proof of their unwavering love that began within the walls of the Academy, Lado Avaliani gave up painting and, with the income from his writing career, fully supported the development of his wife's extraordinary talent.

Natela Iankoshvili, born in Gurjaani in 1918, was so captivated by painting that after finishing school, she enrolled in the Tbilisi Academy of Arts. There, she mastered her professional painting skills under the guidance of renowned artists Moses Toidze, David Kakabadze, Lado Gudiashvili, and Sergo Kobuladze. Iankoshvili entered the independent creative arena shortly after the end of World War II, when the ideological imperative of social realism was still strong. Despite this, the artist attracted widespread attention because she did not obey the common demand to create thematic images dictated by Soviet ideology. Hailing from Kakheti, she established her own creative principles with Kakhetian directness and persistence, and thus created an individual expressive language. Perhaps that's why David Kakabadze admired her "coloristic perseverance," expressed in her dedication to black and green hues. Art historian Shalva Amiranashvili, while evaluating Natela Iankoshvili's first solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in 1960, observed a "boiling of the soul" in her works, and predicted a bright future for her.

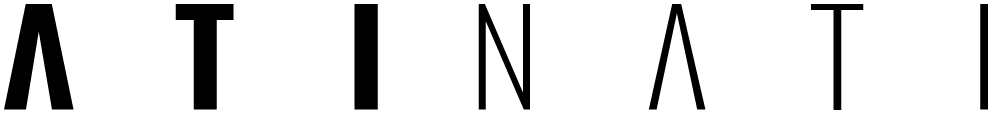

Natela Iankoshvili. Untitled. Oil, canvas. 90x70. 1970. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Natela Iankoshvili. Autumn. Oil, canvas. 100x70cm. 1970. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

At the same time, the lapidary color palette (green velvet against a black background), and the effective use of light and shade on the woman's face, reveal a new perspective of the development of the artist's talent, reflected in the portraits of the later period. This is especially true for the portrait of her father, which received high praise from the artist's teacher Sergo Kobuladze. This new way in her painting is marked by replacing neo-romanticism with neo-expressionism. In this case, the artist did not rely on traditional light and shadow distribution to express the model's facial features in the portrait composition; instead, she used expressive modeling of the form illuminated by subtle nuances of green paint against a dark background, much like her genius predecessor Niko Pirosmanashvili. This comparison with Pirosmani is no accident; it is often stated so in scientific literature about Natela Iankoshvili. What could these two artists have in common besides both being children of the fruitful land of Kakheti, and that the year of Pirosmani's death and Natela Iankoshvili's birth coincide - 1918? However, the most significant similarity was their special love for the color black: Pirosmani painted on black oilcloth, while Iankoshvili covered her canvas with black paint. Both painters attempted to achieve maximum expressiveness using limited expressive techniques.

Portrait and landscape painting held a special place in Natela Iankoshvili's work. A retrospective of her pieces from different periods reveals her effort to captivate the viewer by gradually increasing the color intensity. Color in her paintings appears unexpectedly as an avalanche, and glows with an inner radiance, mainly due to her devotion to the black background. In contrast to her early paintings, Iankoshvili's later works feature nuances of black, achieved by mixing different colored pigments or lightening the dark background with touches of white lead. This evokes the impression of a "flickering" background, making the canvas appear more dynamic, and adding a special effect to the artist's landscapes.

In her portraits, Natela Iankoshvili depicts individuals with a strong will. Her portraits often follow a similar compositional scheme, with the model placed in the center or slightly to the left of the picture plane. Models are typically shown from the knees up, and occasionally from the waist up. The artist often returned to the same model, however, always with a different entourage. This is the case with several portraits of the actress Zina Kverenchkhiladze. They differ in the decorative and colorful depiction of her clothing, but are similar in conveying the strong will reflected in her expression. The powerful impulses coming from her face seem to charge the audience. In Iankoshvili's portraits of actresses Dodo Chichinadze and Medea Japaridze, the irregular brush strokes in various directions help to reveal their inner emotional world. This effect is further enhanced by highlighting the beauty of the model's facial features, which shine against the black background. Unlike her early portraits, where the artist revealed the inner drama of the model's character, in her later works, Iankoshvili accentuated the theatrical and spectacular aspects of the portrayed, as evidenced by the decorativeness of the clothing accessories in Portrait of Ballerina Maria Bauer.

The portrait of a girl holding a book, created by the artist in her early period, which is preserved in the Art Museum of the National Museum Association of Georgia, is noteworthy. Against a black background, a young woman at the center of the composition is wearing a red floral dress under a white gown and holding an open book. The contrasting colors of black, white and red emphasize her quiet, slightly sad expression.

Natela Iankoshvili. Student. Oil, canvas. 84x60

The portrait of a young woman in a red décolleté dress is rather striking. The artistic effect is achieved through the contrast of vibrant colors against the black backdrop. Against this dark background, an invisible light source, typical of the artist, highlights the enchanting facial expression of the woman, giving her an inner glow; sparks seem to fly from her black eyes, and her curly black hair, set against the dark background of varying shades, stands out distinctly and frames her pale face. Her bare shoulders and the smooth, nacreous forms of her breasts seen within the red décolleté dress are revealed by the contrasting colors, connected to each other by the dark background of the picture plane.

Natela Iankoshvili. Woman in a red dress. Canvas, oil. 100х60. 1969. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

While conveying the texture of the models’ clothes, the artist skillfully adjusts the nature of the brushstrokes running on the picture plane to the texture of the fabric: In some places, it is pasty and heavy; in others, it is light and transparent.

Natela Iankoshvili never followed the path of detailing and fragmenting, since it was more critical for her to achieve integrity and unify the artistic form. A holistic perception is characteristic of our national artistic vision of form. This wholeness was achieved not only through compositional structuring, but also by the women's faces themselves, which dictated that the artist express the harmonious unity of the soul and body of beautiful women, not with the echoes of lyrical-poetic feminine tenderness, but with the demonstration of strong human passions subdued by the power of mind, in which the artist's character traits can be recognized.

Natela Iankoshvili. Mokheve woman. Canvas, Oil. 70x50. 1960

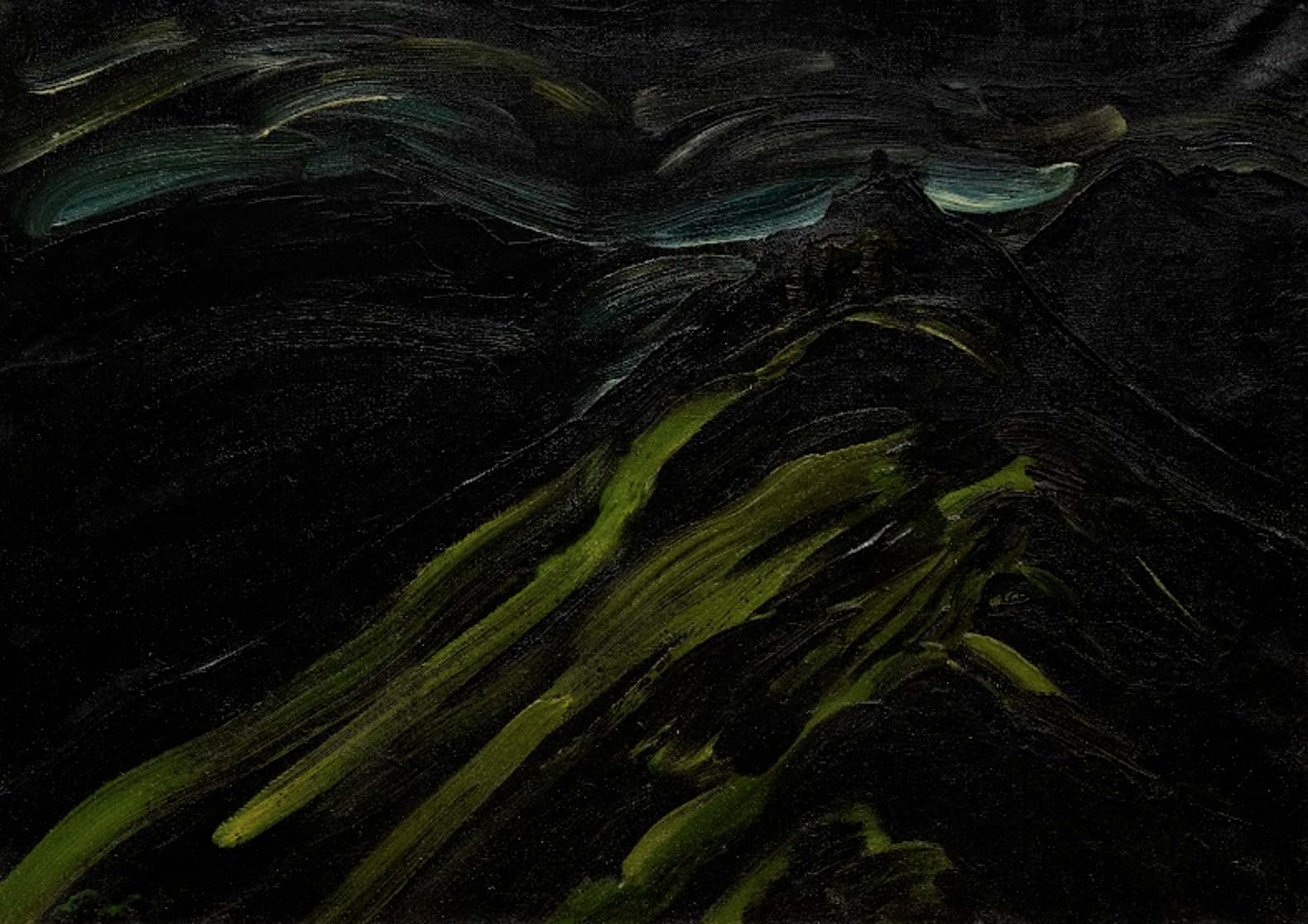

Like her portraits, Iankoshvili's landscape painting always seems to make us feel the "ego" of the artist dwelling in the motifs of nature. Although her landscapes are devoid of people, we can still see traces of them in the remains of churches and monasteries built by unknown Georgian stonemasons; also in the remnants of civilian palaces and fortresses. We also feel evidence of the artist's soul and emotions in each landscape motif depicting the mountainous regions of Georgia. Such is the artist's attempt to read the history lost in the ruins of the arched bypass of Bana, reflected in the ruins of the towers and flat-roofed houses of Svaneti, Tusheti, Pshav-Khevsureti, and Tao-Klarjeti, and executed by the artist-traveler during a number of trips to the regions of Georgia.

Natela Iankoshvili. Bana. Oil, canvas. 65x90. 1992. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Natela Iankoshvili. Ubisi. Oil, canvas. 100x100cm. 1977. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection.

Before directly discussing Natela Iankoshvili's landscape painting, a few words should be said about the creative technique that the artist used to depict both portrait and landscape motifs.

For Natela Iankoshvili, as well as for the renowned portraitist Ketevan Magalashvili from the older generation, the pre-preparatory period for painting was essential. This period involved observing the model, getting to know them closely, and recognizing their character traits. Only after this thorough preparation did the actual portrait session begin, and often proved to be relatively brief. The same can be said about Iankoshvili’s painting process of landscapes: The artist observed the landscape motif outdoors, made a preparatory sketch, and later refined it in her studio. Despite this, Iankoshvili’s landscapes do not appear premeditated or meticulously calculated; instead, they retain an impressive improvisational character. Even the landscapes completed in the studio keep the initial impulse and wave of primary emotion that made the artist pick up her brush and paint that preparatory sketch under the open skies.

As in her portraits, the light source in Natela Iankoshvili's architectural landscapes is invisible. Instead, various motifs on a dark black background appear illuminated from within by the glow of burnt clay. The darkness of the black picture plane takes us to a sort of magical fairytale environment, enhancing a mysterious feeling of "night". For the artist, expressing the landscape motif requires the highlighting of the decorative elements, blended with the monumentality of the artistic form. Iankoshvili achieves this by showing the different characteristics of the brush strokes: In certain areas, through energetic, sweeping strokes, and in others, using delicate, dotted brushstrokes, the artist seems to "sculpt" her landscapes. Despite its conditionality, architectural appearance, and texture imitation, the artwork shares the credibility of each architectural object.

The architectural landscape depicting the ruins of the Georgian church sunk in green, created by Natela Iankoshvili in 1974, is impressive. The brush moves freely across the canvas, revealing the architectural details of the house of God to our eyes: The narthex, windows, and the roof. The artist delicately arranges the stone blocks that make up the facade of the temple like a mosaic, illuminating them as if with sun rays. This chapel, standing alone in the midst of the green forest, creates the impression of having been "sculptured" with a mixture of colorful pigment (yellow-orange) on a black background.

Natela Iankoshvili. Untitled. Oil, canvas. 85x100. 1974. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

During a trip to Khevsureti in 1985, Iankoshvili painted a landscape depicting one of the villages of Khevsureti. The vertical format of the canvas, chosen specially for this motif, shows flat-roofed houses nestled among greenery on the slopes of a high mountain. In place of the sky, two energetic strokes of white-yellow paint form a semi-circle at the top of the mountain, balancing the achromatic colors of black and green. It seems that this landscape, with its magical mysticism, shares with us the mystery of the cosmic night ("moonlit night") characteristic of Pirosmani, and so close to Natela Iankoshvili.

Natela Iankoshvili. Khevsureti Landscape. Canvas, oil. 110x75. 1985. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Natela Iankoshvili. Vardzia. Oil, canvas. 120x75cm. 1994. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection.

In 1992, when the artist created the landscape of Pshavi, she gave the village a legendary appearance. This was achieved through a combination of black and dark, velvety green colors, nuanced yellow paint mixed with white lead, and dotted brushstrokes. It can be stated with confidence that with this work, the artist took the path towards complete abstraction of the landscape. She presented the monumentalism of the nighttime buildings of Pshavi with amazing expression.

Natela Iankoshvili. Pshavi Fortress. Canvas, oil. 121x75. 1992. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Among the urban landscapes painted by Natela Iankoshvili, two should be highlighted: One depicting Darejan's Palace, a notable attraction in Tbilisi, and another showing Rome's main landmark, the Coliseum. Like her rural landscapes, these urban scenes are devoid of people and feature the artist’s customary black background. For the landscape depicting Darejan's Palace, Iankoshvili chose a vantage point that highlights the beauty of the chiseled decorative elements of the balcony, the main structural feature of the vertically oriented facade.

In the second case, Iankoshvili focuses on the rhythmic alternation of arches in a heavy, massive, half-collapsed rotunda-like building, centrally located in the "eternal" city.

Natela Iankoshvili. Darejan's Palace. Canvas, oil. 86x116. 1992. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Natela Iankoshvili. Colosseum. Canvas, oil. 80x64. 1970. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

When depicting her silent landscapes, the artist operates on the picture plane, with abstract arrays of colors created by nuanced green paint "raised" from the black background. The place of the sky is taken by undulating traces of bright (typically yellow) brushstrokes thrown expressively by the artist. At first inspection, the structure of the picture plane, formed by sharp brush strokes, is similar to the abstract-expressionist solution of the landscape motif. In Natela Iankoshvili's landscapes, created in the Soviet Union in the 1970s, on the black picture plane, the tip of the brush, covered in one or two bright (yellow, orange) paint colors, ran freely and left an unusually shaped mark on the black background (Il.12) The artist sometimes cut the plane with vertical trees and thereby intensified the feeling of rhythm for the viewer; sometimes, she left only a spiral decorative mark with nuanced green paint, darkened in some places, and scraped with the palette-knife in others. An architectural motif lost in the green mess is visible in the compositional center of the landscape. When depicting Georgian architectural landscapes (Sioni of Ateni, Vardzia, Shio-Mgvime, Bana, and others), the artist used the method of the Georgian modernists, her teachers, David Kakabadze and Lado Gudiashvili, who mastered rendering the pictorial plane-space in landscape that was characteristic of the national artistic sense of shape.

In addition to painting, Natela Iankoshvili worked in graphics. In 1966, she made 18 pictures for the Japanese version of Shota Rustaveli's ‘The Knight in the Panther's Skin’. In contrast to painting, where the color dictates the character of the line, in Iankoshvili's graphics, lines entirely subdue the color. This essential responsibility inspired her to illustrate this epic poem, said by many to boast human value and defining the Georgian identity, in such a way that it stood out among the various artistic solutions offered by prominent artists at different times. Iankoshvili selected 18 key themes of the poem and illustrated them based on the portrait images of the main characters. The artist entrusted the personal characterization of the main characters, which is revealed in their relationship with each other, to the lines drawn on the surface of the paper.

With the rhythmic stream of silhouetted lines against a black background, Iankoshvili achieved a monumental decorative arrangement in her paintings, reflecting the traditions of national mural art. The laconic compositional structure of each graphic work, with its restrained use of color, is built on the stark contrast of black and white. For example, in the scene of Tinatin's coronation, the gray-bearded and gentle King Rostevan, and the radiant expression of his sunshine-like daughter, are presented with restrained modesty against a black background. Striving to harmonize contrasts is characteristic of the expressive language in ‘The Knight in the Panther's Skin,’ as well as in Natela Iankoshvili's painting. In this case, the artist also builds the composition using the counterpoint of opposing forces typical of her style.

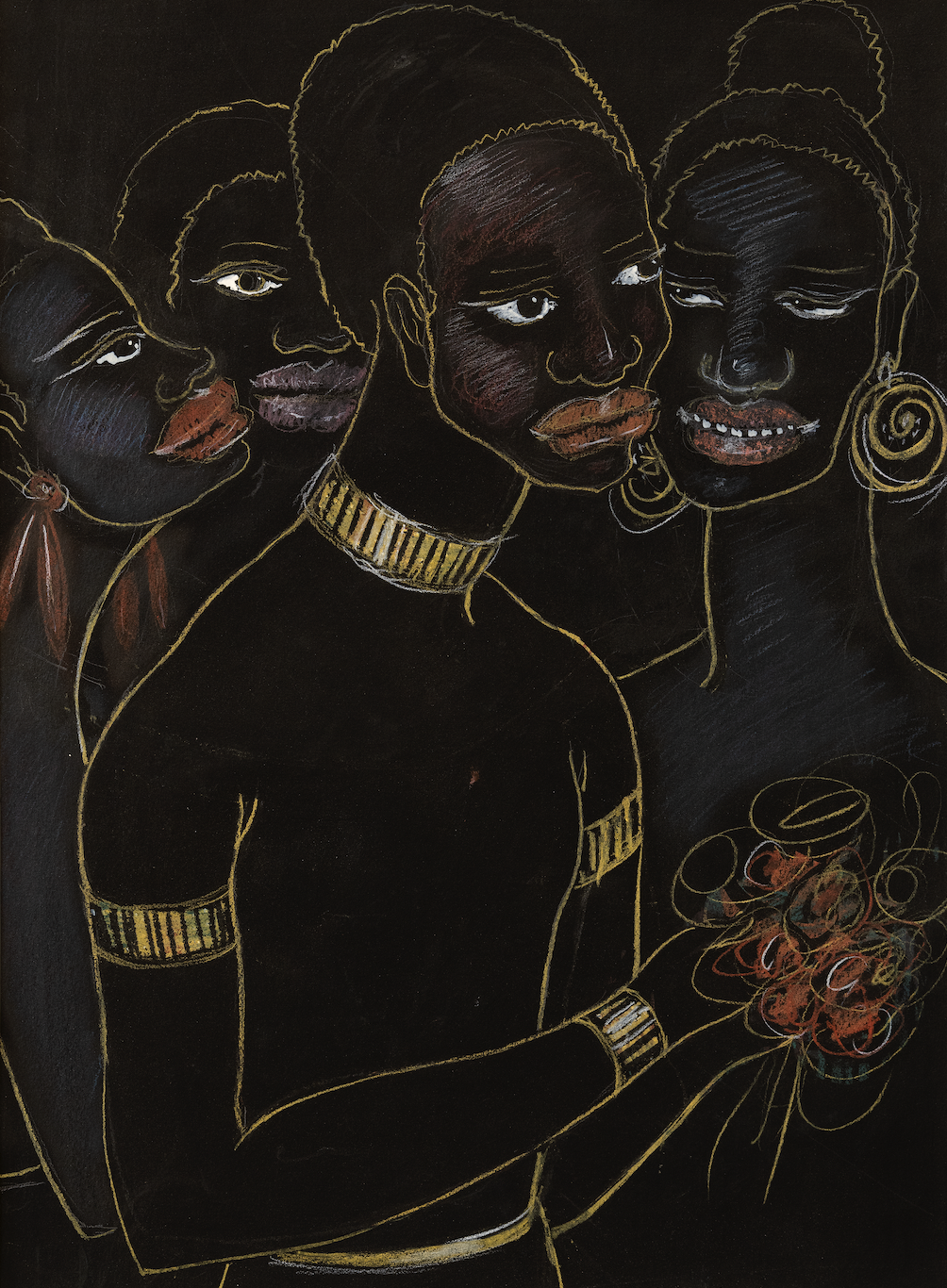

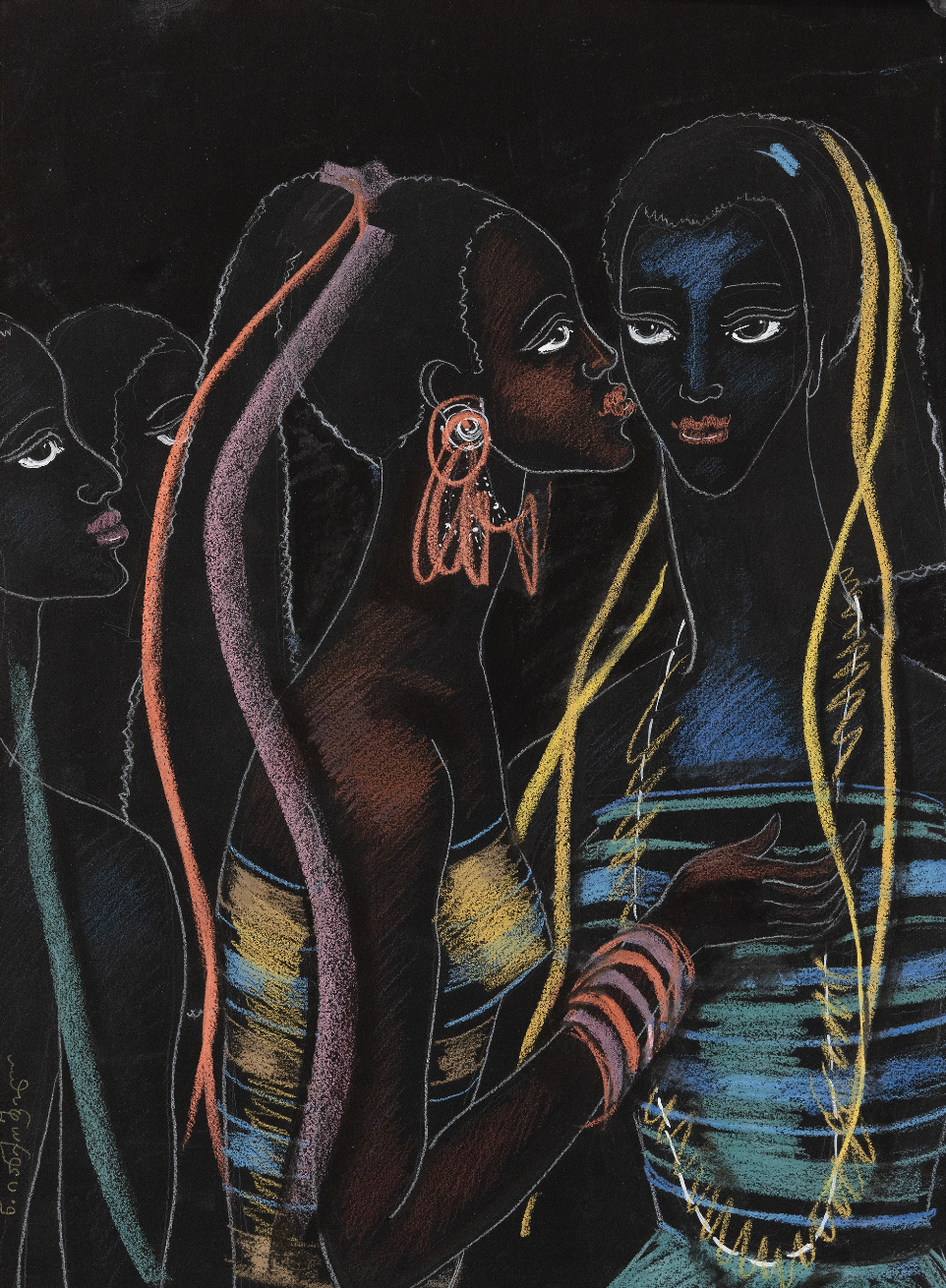

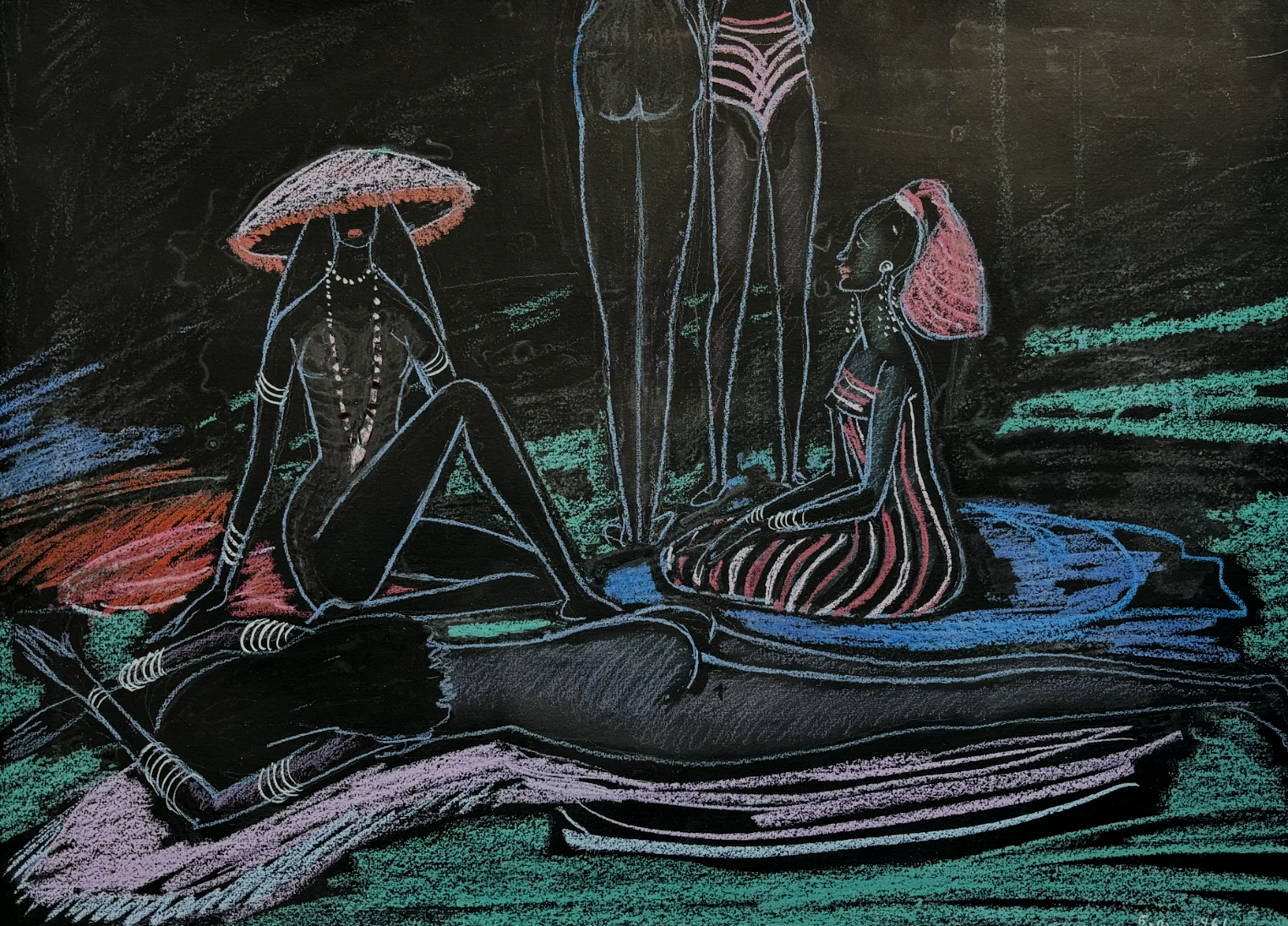

Natela Iankoshvili. Grigol Orbeliani in Bethany Church.Oil, canvas. 43×32. 1960

Natela Iankoshvili's remarkable ability to tackle challenging artistic tasks with great courage is evident in her graphic series inspired by her trip to Cuba. During this journey, she aimed to paint black on black background, capturing her impressions of the Cuban experience. In 1961, Iankoshvili, with other Soviet cultural figures, traveled to the island of Cuba, where the revolutionary fervor of the Cubans was still vibrant. This trip was followed by a visit to Mexico, and the artist created live sketches everywhere she went. Back in her homeland, Iankoshvili published a book ‘Journey to the Heroic Island,’ in which she depicted her impressions of the trip and included 40 illustrations. The artist focused on the plastic figures of colored Cuban women, capturing the extraordinary resilience of their bodies, which seem ever poised to dance. She also highlighted the decorative sombreros of the Mexican men. The artist outlines all this using a dynamic white and gray silhouette line against a black background. The artist's meticulous detailing of decorative accessories, such as jewelry and headdresses, is especially impressive.

Natela Iankoshvili. Cuba, Curaçao. Paper pastel. 42x32. 1961

Natela Iankoshvili. Cuba, Cuban girls. Paper pastel. 43x31. 1962

Natela Iankoshvili. Cuba, Negro women on the beach. Paper pastel. 31x41. 1961

In addition to the aforementioned graphic series, Iankoshvili illustrated works by Victor Hugo, Emile Zola, Charles Dickens, and other classic writers. She also created a number of easel graphics, consistently focusing her creative interest on overcoming challenges through diverse use of lines and color.

Natela Iankoshvili was one of the outstanding artists of the 20th century. She affected quintessentially in the history of Georgian art.