Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

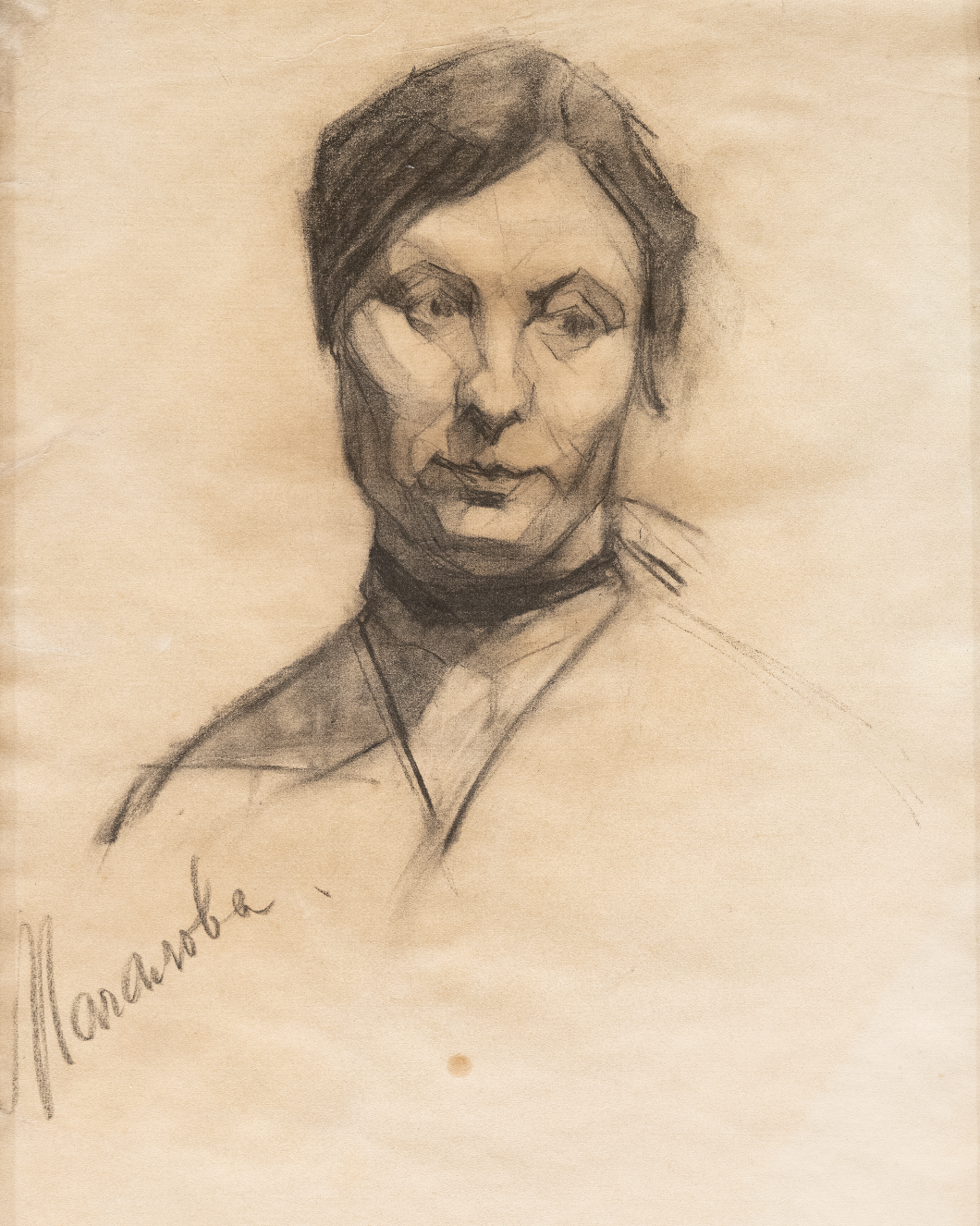

The history of Georgian fine arts has preserved the sad love story of two great artists. It was love with a tragic end that left an irreversible wound on Ketevan Magalashvili's noble soul and the entire cultural elite of Georgia. In 1938, Ketevan’s beloved friend, Dimitri Shevardnadze, one of the most famous of Georgian artists, was labeled an "enemy of the people." Later, he was imprisoned and executed. They say that for a time afterwards, Ketevan refused to leave the house and locked herself in. According to her family members, she even stopped working, at a complete loss, asking again and again, "Why?" "What for?" No-one could answer these questions.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Portrait of Dimitri Shevardnadze. Oil, canvas

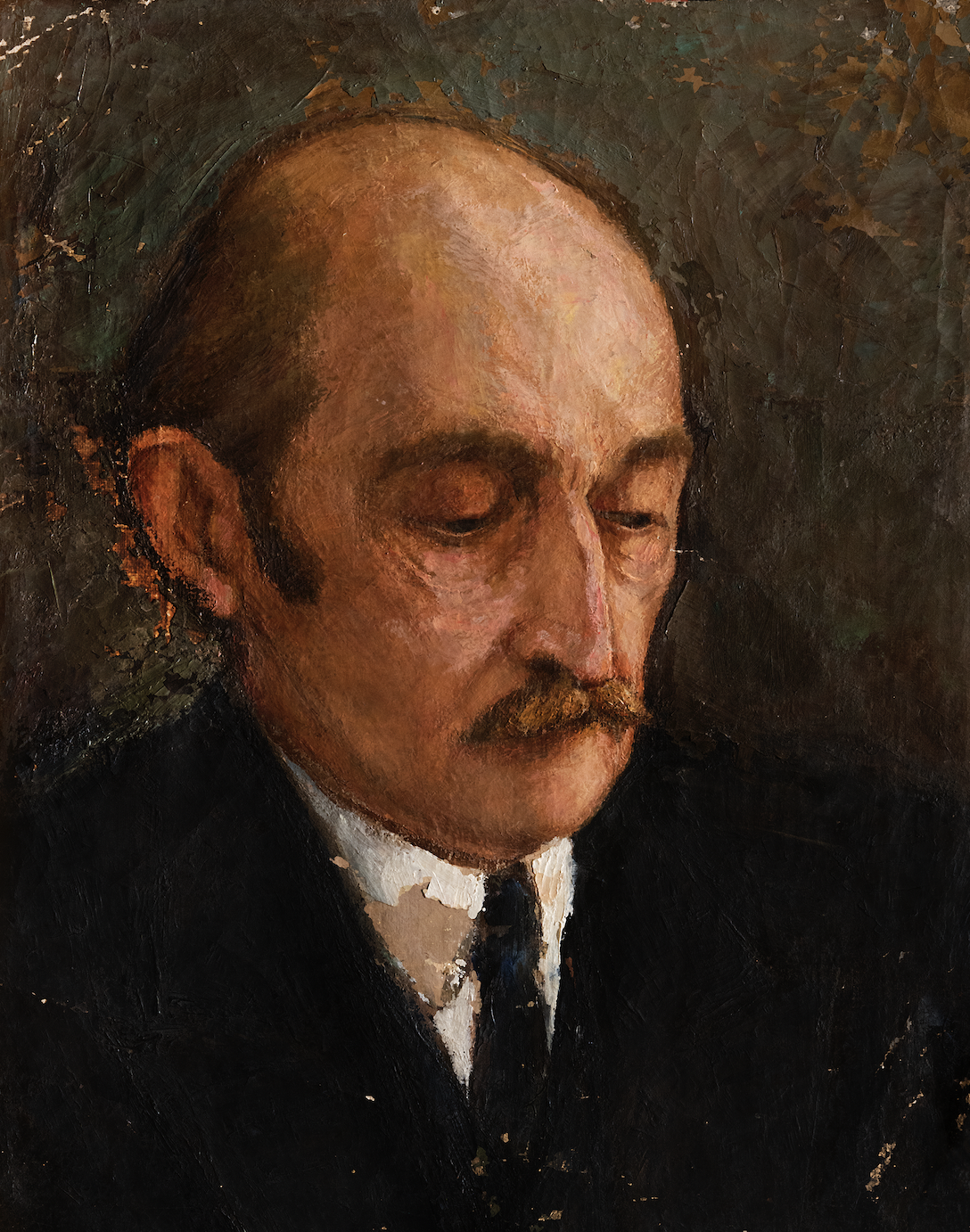

Ketevan Magalashvili was born on April 19, 1894, in Kutaisi, to financier and amateur artist Konstantine Magalashvili and his respectable wife Taso Kandelaki. They had three sons and two daughters. An outstanding artist of the older generation, Romanoz Gvelesiani, preserved for us a portrait of Ketevan's father Konstantine, painted in his youth. Soon, the Magalashvilis moved to Tbilisi, where Ketevan was admitted to the third women's gymnasium of Tbilisi.

Ketevan Magalashvili’s father Konstantine Magalashvili. Oil, canvas. Portrait reproduction by Romanoz Gvelesiani

A strong desire for painting led the young Ketevan Magalashvili to continue her studies at the Painting and Sculpture School of the Tiflis Fine Arts Support Society, where she learned the basics of painting under the guidance of outstanding artists Oscar Shmerling, Iakob Nikoladze, Ludwig Longo, Mose Toidze, and Henryk Hryniewski. In 1914, to complete her education, she left for Moscow, and successfully passed the entrance exams to the Moscow Art School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. Back in her homeland in 1916, Ketevan became a member of the Georgian Society of Artists founded by Dimitri Shevardnadze. In 1918, she started collaboration with the Giorgi Jabadari Theater Studio, where she made sketches of national costumes.

In parallel, at the request of Ivane Javakhishvili, honorary chairman of the Georgian Society of Artists, Ketevan Magalashvili began searching for material about traditional national clothing preserved in various parts of Georgia. During that time, she painted a portrait of her aunt living in Atskuri, Nutsa Magalashvili-Sulkhanishvili, wearing a national headband pad.

In the early stages of the development of Ketevan Magalashvili's artistic technique, those she chose to portray were objects of reflection rather than subjects of psychological awareness. The artist's transition to subjectivism began in 1922, when Magalashili exhibited a wholly unconventional portrait of Iakob Nikoladze at the sculptor's anniversary evening. The large pictorial portrait, depicting the famous artist in the neo-romantic style, determined portraiture as the dominant genre in Ketevan Magalashvili's creative work. With this portrait, the young artist not only won recognition, but also opened a new page in the development of the genre of national portraiture. In the aforementioned portrait, the artist managed to merge the common and the generalized with the particular, recognizing a sculptor's own individualism while emphasizing the painter's artistic character.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Portrait of Iakob Nikoladze. Oil, canvas

In 1919, in independent Georgia, the state actively discussed the issue of sending fellows to leading foreign centers in various fields to train young specialists. As a result of an unbiased vote in the Georgian Society of Artists, taking into account talent and hard work, at the end of 1919, a list of scholarship-holding artists was compiled for sending to Europe, among which Ketevan Magalashvili was the fourth. Since the political situation in Georgia changed in February 1921, the sending of young people abroad was delayed. However, in 1923, Magalashvili, a scholarship holder, was sent from Soviet Georgia, first to Germany, and afterwards to France. In Paris, she was admitted to the Filippo Kolaros Free Academy together with Elene Akhvlediani. As a student of the Kolaros Academy, Magalashvili made sketches of naked models. The artist applied quick pencil lines to convey the plasticity of the female body presented in different poses.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Sketch. Pencil, paper. 44,5x32. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Ketevan Magalashvili. Sketch. Pencil, paper. 33x25. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Ketevan Magalashvili. Sketch. Pencil, paper. 33x24,5. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Ketevan Magalashvili. Portrait. Charcoal, pencil, French paper. 58X44. 1920s. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Ketevan Magalashvili. Pilot. Charcoal, pencil, French paper. 57X47. 1920s. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

In addition to her studio work, Magalashvili dedicated her free time to painting portraits. In Paris, the capital of European painting, she participated in exhibitions together with David Kakabadze, Lado Gudiashvili, and Elene Akhvlediani. The portraits painted in Paris - Irakli Orbeliani, Tanya Kakabadze, Elene Akhvlediani, Felix Varlamishvili, Sunana Gambashidze, and others, are distinguished by their fast "alla prima" technique, surprisingly poetic and filled with a sense of freedom, light and pleasantry.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Portrait of pianist I. Orbeliani

Ketevan Magalashvili. Tatyana Kakabadze

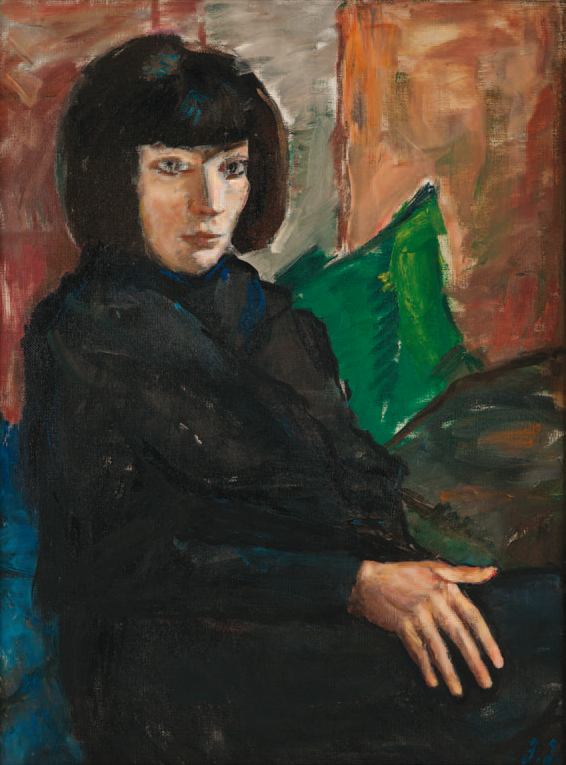

One of the best portraits of Elene Akhvlediani, Magalashvili’s closest friend, belongs to this period. The portrait points to the place of the artist in society. For this purpose, Magalashvili used special markers, for example, in the background of the portrait of Elene Akhvlediani, the lower part of the frame of the picture hanging on the wall is visible, while the person portrayed is holding an album depicting the work of the famous artist El Greco - an artist she highly appreciated.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Portrait of Elene Akhvlediani. Oil, canvas

Ketevan Magalashvili. Portrait of Elene Akhvlediani. Oil on canvas. 1960. Shalva Amiranashvili’s Museum

In 1926, Ketevan Magalashvili came back to Georgia and started working as a librarian in the National Picture Gallery, and later, in 1933, as an art-restorer in the Metekhi museum. In a self-portrait drawn in 1928, Magalashvili vividly demonstrates her unwavering will to create highly individual handwriting, expressed through a piercing glance directed towards the viewer. The warm color palette of the self-portrait and the free use of the brush stroke reveal feminine tenderness, gentleness, refined aristocracy, and at the same time, creates a feeling of simplicity and sincerity.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Self-portrait

Ketevan Magalashvili. Self portrait. Oil, canvas. 1969. Shalva Amiranashvili’s Museum

The pictorial portrait-etude of Grigol Tsereteli, the well-known Hellenist and founder of the Georgian school of classical philology, was painted in the early 1930s. Unfortunately, like Dimitri Shevardnadze, this great scientist and appreciator of Ketevan Magalashvili’s talent fell victim to the 1930s repressions.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Grigol Tsereteli. Oil, canvas. 38х31. 1933. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Ketevan Magalashvili. Portrait of A. Ishkhneli. Oil, canvas. 1957. Shalva Amiranashvili’s Museum

During the heyday of social realism (1930-1940s), Magalashvili also had to compromise with the Soviet regime’s imperative of social realism when she created portraits of workers, Stakhanovites and brigadiers of an enterprise in Samgori. It was obvious that the poetic spirit characteristic of the artist's creative nature could not come into harmony with the prosaic nature of the object to be portrayed. As a result, the naturalistic perception dominated. These were more conceptual portraits than artistic faces, recorded with distinct marks. However, the artist quickly adapted to the new environment, discovering the genre of still life, which was occasionally substituted with landscapes. Magalashvili’s still-lifes of this period often depict wildflowers, roses, sweetbrier branches, national pottery, and glass vases. The artist appears to be searching for the delicacy stored in a seemingly conventional plain form. For a painter who preferred simplicity, beauty was veiled and needed to be recognized.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Still life. Colour pencils, paper. 38X30. 1956. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Ketevan Magalashvili. Still life with Roses. Oil, canvas. 37x48. 1960’s. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

In addition to still-lifes, Ketevan Magalashvili's works include landscapes, in which the artist, filled with a type of nostalgic poetry, depicts scenes of Old Tbilisi and her native Kakheti, mainly viewed from the top and saturated with a decorative rhythm of color and lines. However, Magalashvili considered herself primarily a portraitist, and remained devoted to this genre, as evidenced in the portraits of artists she painted from the 1950s until the end of her life. To break up the monotony, she would focus on the model's body placement, gaze trajectory, hand position, background, and mild use of varied surroundings. That is why the artist's attention, and the viewer's perception, is always drawn to the inner movement of the person's soul and the delicate representation of their emotions.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Gremi. Pastel, canvas mounted on board. 50X68. 1961. This work is part of ATIANTI Private Collection

Ketevan Magalashvili. Landscape. Oil on board. 25X31. 1963. ATINATI Private Collection

In the context of post-Stalinist liberalization, Ketevan Magalashvili's work demonstrated how productive the work of a talented artist could be. The artist's technique improved by the year, leading to her complicating the forms of compositional building in portraits. The artist actively worked on portraits in the open air, paying close attention to color and light.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Tina with read cloak. Oil, canvas. 70х51. 1966. This work is part of ATIANTI Private Collection

Ketevan Magalashvill. Ketuna. Oil, canvas. 70X50. 1969. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Whether painted in exterior or interior environments, the painter's art of textural processing of accessories and entourage is flawless. With carefully chosen graphic nuances, the plastic expression of this or that portrait is enhanced. These include the portraits of Shalva Dadiani, Sviatoslav Richter, Konstantine Gamsakhurdia, and Sergo Zakariadze.

The faces of the women in the mentioned portrait gallery fascinate us with their sincerity, similar to Fayum portraits, sophisticated aristocracy, artistic grandeur, the self-confidence of Solomon Virsaladze, a theater artist with a presentable appearance, the sad expression of the movie star Nato Vachnadze and the cheerful, open natured women's faces.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Portrait of Nato Vachnadze. Oil, canvas. 40x30. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Ketevan Magalashvill. Tinatin Virsaladze. Oil, canvas

Ketevan Magalashvili. Tina Magalashvili. Oil, canvas. 60х41. This work is part of ATINATI Collection

Ketevan Magalashvili. Manana's Portrait. Oil, canvas. 60x81. 1963. ATINATI Private Collection

Ketevan Magalashvili. Martha. Oil, canvas. 74х53. This work is part of ATIANTI Private Collection

One of the meaningful works is the prophetic portrait of pianist Vera Steshenko-Kuftina, wife of archaeologist Boris Kuftin, a researcher of Georgian cultural monuments. At first glance, the female pianist sitting on a chair appears to be in a free stance, which contrasts with the state of the woman's face and lengthy fingers entwined. This is accentuated by the expression of inner tension, fear, and excitement in the woman's gaze directed at us. It should be mentioned that the female pianist committed suicide shortly after Ketevan Magalashvili painted her portrait.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Portrait of V.Kuftina-Steshenko. 1941. Shalva Amiranashvili’s museum

The entire antipode of the mentioned painting - King Tamar’s face full of peace and harmony - dates back to the same time. Magalashvili, who was well aware of four excellent fresco-portraits of King Tamar in Vardzia, Betania, Kintsivisi, and Bertubani, offered the audience a modern image of the ruler. She created an outstanding shining face for the great king by following the ideas of Georgian monumental painting from the Middle Ages, with a flowing linear rhythm and bright colors, which gives the feeling of tranquility and airiness.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Queen Tamar. Oil, canvas. 1944. Shalva Amiranashvili’s museum

The appeal of Ketevan Magalashvili's portraits of different times lies in the fact that she painted portraits of only those with interesting spirituality and creative potential. It fascinated the artist to depict the hidden aspects of their souls, revealing their temperament, intelligence, and spiritual aristocracy. Particularly noteworthy in this regard are the portraits of Manana Khidasheli, Eliso Virsaladze, and Manana Kikodze.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Portrait of M. Khidasheli. Oil, canvas. 1958. Shalva Amiranashvili’s Museum

Ketevan Magalashvili. Portrait of Eliso Virsaladze. Oil, canvas. 1960. Shalva Amiranashvili’s Museum

Ketevan Magalashvili. Eliso Virsaladze. Oil, canvas

Ketevan Magalashvili. Manana. Pastel, paper. 58x45. This work is part of ATIANTI Private Collection

Ketevan Magalashvili. Unfinished Portrait. Oil, canvas. 41х36. 1933. This work is part of ATIANTI Private Collection

In the 1960s, the artist preferred pastels over oil paint. The delicate, matte coloring and expressiveness of the lines that characterize this material appear to be better adapted to the creative tasks she assigned herself at the time. This is how a distinct collection of portraits came to be developed, featuring the memorable faces of Elene Akhvlediani, Nani Shalikashvili, Manana Samadashvili, and others.

Ketevan Magalashvili. Portrait of Anna Shalikashvili” Pastel, cardboard. 48X43. 1970. ATINATI Private Collection

Magalashvili never exaggerated the facial expressiveness of the people she portrayed; she consistently created a person's character by using halftones, and in doing so analyzed the sensations and emotions firmly engraved in the depths of the character's soul. In this perspective, Ketevan Magalashvili's method is worth mentioning. Before starting to paint a portrait, the artist did some preliminary work, which included getting to know the models, engaging with them, and observing their gestures, facial expressions, and behavior. Only after memorizing all of the models' distinguishing characteristics did the artist begin a session of painting in color, which she sought to make brief and not at all tiring for the model. Magalashvili frequently created preparatory etudes, which she meticulously adjusted to the final version of the picture. At various times in her creative career, the artist would return to painting portraits of particular models she found to have intriguing psychetypes. To better understand the character, the artist recorded previously invisible strokes of the movement of the human soul in the form of a sketch and a finished pictorial portrait. In addition to the material, these portraits differ in their artistic style, corresponding to the aesthetic trends of different periods.

Magalashvili's tremendously valuable work came to an end when she passed on May 30, 1973. She was buried in Tbilisi, at the Didube Pantheon of Public Figures.

Ketevan Magalashvili's portraits, which capture true sensations of the gentle movement of the human spirit, hold both historical significance and high creative value as a portrait series of public individuals.