Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

After Niko Pirosmanashvili, Lado Gudiashvili is arguably the most extensively discussed Georgian artist. Like Pirosmani, Gudiashvili's initial recognition came primarily from international art appreciators. Just as Pirosmani was a mythic figure in Georgian culture, Gudiashvili also gained significant admiration among Georgians.

_Lado_Gudiashvili_(1896-1980).jpg)

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980)

Lado Gudiashvili was born in 1896. In 1910, he was admitted to the Painting and Sculpture School of the Caucasus Fine Arts Support Society in Tiflis, where he studied under teachers Oskar Schmerling, Iakob Nikoladze, Boris Fogel, Henryk Hryniewski, and others. In 1914, Gudiashvili graduated with top honors and began working as a drawing teacher at the Tiflis Boys' Second Gymnasium. Simultaneously, he collaborated with the editorial office of the magazine ‘Theater and Life’ as an illustrator.

From 1915, Gudiashvili began actively participating in art exhibitions, where it became evident that he was more interested in modernist movements – Futurism, Expressionism, and Symbolism – than in realistic painting. Lado Gudiashvili's passion for symbolism became particularly evident after he connected with ‘Tsisperkantselebi’ (The Blue Horns), a group of symbolist poets who moved from Kutaisi to Tbilisi, and whose printed issue ‘Dreamer Pasans’ was illustrated by the artist.

In 1916, when artist Dimitri Shevardnadze returned from Munich and founded the Georgian Society of Artists in Tiflis, Lado Gudiashvili became an active member. Between 1916 and 1917, Gudiashvili, along with several other artists, participated in scientific-artistic expeditions organized jointly by the Georgian Historical and Ethnographic Society and the Georgian Society of Artists. These expeditions aimed to study and preserve Georgian architecture, seeing the participants making copies of frescoes and collecting them for the museum.

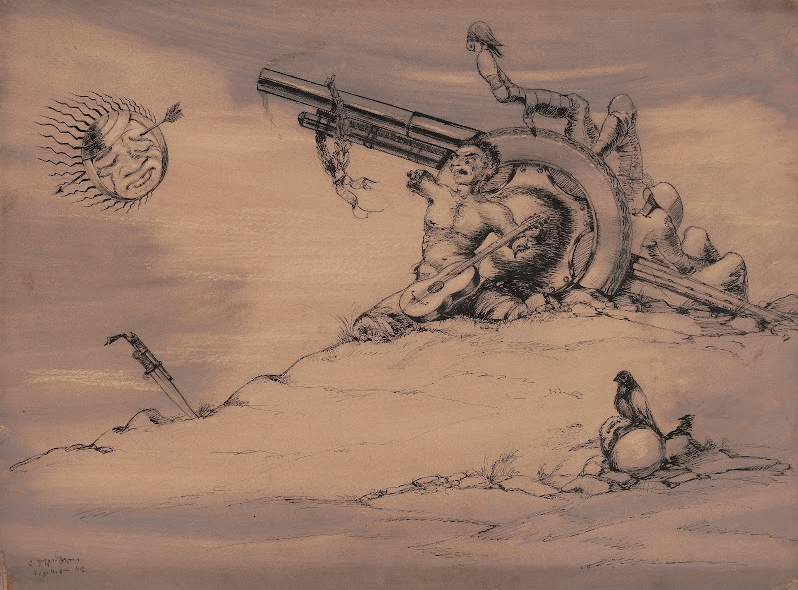

_“Precious_gift”_Mixed_media_on_toned_paper_43x29,5_cm_1965._ATINATI_Private_Collection__Large.jpeg)

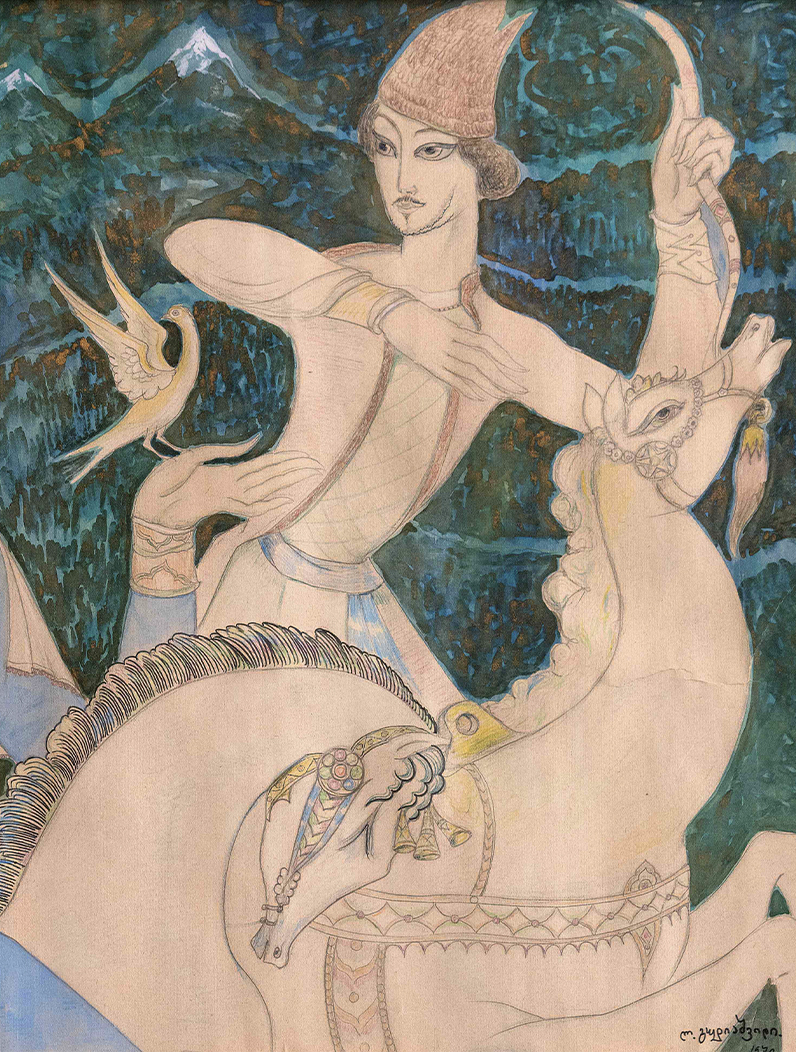

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). Precious gift. Toned paper, mixed media. 43x29,5. 1965. ATINATI Private Collection

Gudiashvili participated in expeditions to Nabakhtevi and Davit-Gareji, and in 1917, he took part in the third, particularly significant, expedition to the Tortum-Ispir region. The purpose of this expedition was to study the monuments of Georgian architecture in the territory of historical Tao-Klarjeti and make copies of damaged frescoes. As Gudiashvili later recalled, visiting and studying these monuments had a lasting impact on his work, particularly the development of his distinctive "Georgian artistic style."

During that period, Lado Gudiashvili, along with Kirill Zdanevich and Ziga Valishevsky, painted the renowned ‘Fantastic Tavern’ on Rustaveli Avenue in Tbilisi. Soon after, other artists, including Serge Sudeikin, Alexander Zaltsman, David Kakabadze, and Mose and Erekle Toidze, joined them in painting the poets' and artists' gathering place – Cafe ‘Khimerioni.’

__Bruniquel__Watercolor_on_paper_34,5x25_cm_1924._ATINATI_Private_Collection__Large.jpeg)

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). Bruniquel. Paper, watercolor. 34,5x25. 1924. ATINATI Private Collection

An important event in 1919, which ultimately led to Lado Gudiashvili, David Kakabadze, and Shalva Kikodze being sent to France as state scholarship recipients from independent Georgia, was their success achieved at the spring and autumn exhibitions organized by the Georgian Society of Artists. Gudiashvili's numerous works displayed at both exhibitions revealed his unique style, which captured the essence of Old Tbilisi's bohemian life, a theme partly inspired by Niko Pirosmani's work. This artistic vision seemed to come to life even more vividly during his time in Paris. The artistic method developed by Gudiashvili while still in his homeland envisaged a neo-romantic perception of reality by combining the expressive language of medieval Georgian monumental painting with the technical achievements of modernist art.

In Paris, Lado Gudiashvili became actively involved in the artistic life of the French capital. His expressive, plastic lines on the canvas introduced the European audience to an exotic and enchanting world they had never seen before. The monumental and decorative solution of Gudiashvili's compositions, achieved through the rhythmic arrangement of sharp, expressive silhouettes, vibrant colors, and well-structured elements, did not go unnoticed by French art enthusiasts. Renowned critics such as Maurice Raynal, who dedicated a monograph to Gudiashvili, along with André Salmon, Raymond Cogniat, Pierre Worms, and others, praised the young Georgian artist.

Lado Gudiashvili led a creatively vibrant life in Paris, where he designed theater sketches for performances, painted the walls of the ‘Caucasian Club,’ and, alongside other Georgian artists, participated in solo and group exhibitions in Paris and other European cities. The prominent Spanish artist Ignacio Zuloaga enriched his collection with the works of the young Georgian artist, joining numerous other collectors in the acquisition of Lado Gudiashvili's pieces. Yet, despite his widespread recognition, the artist suffered from nostalgia for his homeland.

__Date__Gouache_on_paper,_38_X_32_cm._1973._ATINATI_Private_Collection__Large.jpeg)

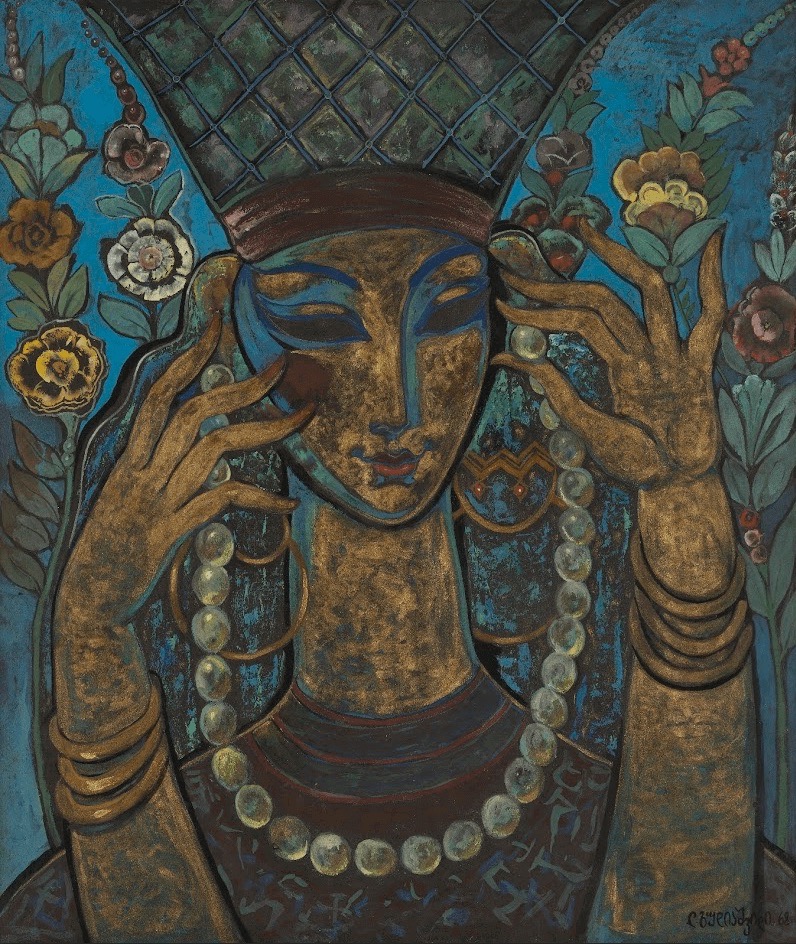

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). Date. Paper, gouache. 38x32. 1973. ATINATI Private Collection

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). Spanish Friends. Canvas, oil. 73x60. 1922

In November 1925, Lado Gudiashvili returned to his longed-for Georgia, only to discover a drastically transformed environment. Thus began a new, complex, and internally conflicted phase of his artistic career. The challenges of this period were primarily due to the oppressive Soviet regime, where ideological pressure, particularly in the cultural sphere, was intense. After returning from Paris, Gudiashvili held an exhibition to showcase the works he had created while abroad. Reviews of the exhibition, initially restrained and later subtly critical, noted that the artist had not escaped formalism and that his works seemed disconnected from the everyday realities of Soviet Georgia. In response, Gudiashvili quickly created works with social themes, such as ‘Bakurianis Andeziti,’ ‘Death of a Worker-Correspondent,’ ‘Sheep Shearing,’ and others. These were forced compromises for the artist. In this tense atmosphere, meeting Kote Marjanishvili, the reformer of Georgian theater, provided Gudiashvili with much-needed relief. His true friendship with this great director lasted from 1926 until Marjanishvili's death in 1933. At Marjanishvili's request, Gudiashvili began designing the set for ‘Lamara,’ a play by Grigol Robakidze based on the motifs of Vazha-Pshavela. In the same year, 1926, Gudiashvili, together with Dimitri Shevardnadze, also designed the set for Tamar Vakhvakhishvili's pantomime ‘Mzetamze.’ In 1931, Marjanishvili suggested that Gudiashvili work on the artistic decoration for Andria Balanchivadze’s opera, based on the folk poem ‘Arsena,’ which Marjanishvili was directing. Lado Gudiashvili's last collaboration with him took place in 1933, when he worked on the set design of the comic opera ‘Arshin-Mal-Alan’ by the Azerbaijani composer Uzeir Hajibekov. Unfortunately, the play was never staged due to Kote Marjanishvili's death.

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). Sun Woman. Paper, gouache. 80x70. 1968

_“Woman_with_a_Roe_Deer”_Gouache_on_paper_36,3x25,4_cm_1956._ATINATI_Private_Collection_.jpg)

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). Woman with a Roe Deer. Paper, gouache. 36,3x25,4. 1956. ATINATI Private Collection

After returning to his homeland, Lado Gudiashvili created several monumental paintings, among them the mural painting for the interior of the hotel ‘Orient’ and the panel of the central hall of the Tbilisi railway station. Unfortunately, these works were destroyed during the artist's lifetime, and only photographs remain to give us an idea of the extraordinary compositions that once decorated the walls of the hotel: ‘Hunting,’ ‘Legend of the Founding of Tbilisi,’ ‘Girls at the Spring,’ and ‘Georgian Dances.’ Despite the low quality of the black-and-white photographs, the images of people among the decoration of contour lines evoke a poetic and romantic uplift of mood.

__Hunting_in_Okrokana__Colored_pencil_on_a_gold_background,_cardboard,_78_X_56_cm._1970._ATINATI_Private_Collection_Large.jpeg)

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). Hunting in Okrokana. Cardboard, colored pencil on a gold background. 78x56. 1970. ATINATI Private Collection

__The_legend_of_the_foundation_of_Tbilisi_._41,5х33cm._Paper,_graphite_pencil,_quill,_ink._1957._ATINATI_Private_Collection_Large.jpeg)

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). The legend of the foundation of Tbilisi. Paper, graphite pencil, quill, ink. 41,5х33. 1957. ATINATI Private Collection

Lado Gudiashvili's famous portrait of Niko Pirosmani with a roe deer can be interpreted as an echo of Georgian monumental mural painting from the Middle Ages. It demonstrates the artist's desire for generalized, large-scale form. It should be noted that Gudiashvili presented similar works in 1928 at the 16th Venice International Exhibition.

From 1929 to 1931, Lado Gudiashvili created pictorial compositions saturated with expressionist elements: ‘The Guilty Family’ (1929), ‘The Unfortunate’ (1930), ‘No Title’ (1931). It is evident that, to accentuate the content of his compositions, the artist chose to aestheticize ugliness by employing methods of deformation and exaggeration of artistic forms on canvases of various formats. However, in all three instances, despite the original compositional structure and remarkable expressiveness, the artist afterwards did not return to creating works with this approach. On the contrary, his hedonistic attitude toward beauty, personified in the form of a woman and embodied in a beautiful animal (such as Pegasus, roe deer, or an exotic bird) became a defining feature in his later work.

Beginning in the mid-1930s, Lado Gudiashvili made significant contributions to the field of book illustration. His knowledge of the history of Georgian and global medieval art greatly assisted him in adapting the principles of decorative art to literary texts. Gudiashvili illustrated Georgian literary classics using the traditional methods of medieval illustrators, not only creating illustrations, but also adorning the entire book—much like Georgian miniaturists did in the Middle Ages.

It is also important to note that Gudiashvili frequently revisited several key literary works throughout his career. One notable example is Shota Rustaveli's ‘The Knight in the Panther's Skin.’ Each time, however, the artist did not simply repeat his previous approach, but rather enhanced our classical heritage by employing new, innovative techniques and illustrating different episodes. Gudiashvili dedicated much of his career to illustrating masterpieces of Eastern literature, including ‘One Thousand and One Nights,’ the works of Nizami Ganjevi, and Fizuli's poetic compositions, ‘Khosrov and Shirin’ (1956) and ‘Leila and Mejnuni’ (1962). These illustrations demonstrate how seamlessly Gudiashvili integrated the outlook of classical Eastern culture with Western cultural values.

_“Fun_on_the_Balcony”_Mixed_media_on_paper_43x31,5_cm_1942._ATINATI_Private_Collection.jpg)

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). Fun on the Balcony. Paper Mixed media. 43x31,5. 1942. ATINATI Private Collection

At the end of the 1930s, new elements began to emerge in the artist's work, enriched with fresh themes and a corresponding shift in style. The color palette of his works became lighter, and the brushstroke more pastose. However, despite the artist's ongoing creative exploration, no matter what evolutionary development his style underwent, Gudiashvili's unique approach and distinctive manner of expression were always immediately recognizable.

Portraiture played a significant role in the artist's post-Paris work, and can be divided into two groups: the first group consists of portraits of historical figures from the distant past, as imagined by the artist; the second group includes portraits of the artist's contemporaries, who served as his models. Despite this, these portraits only partially preserve the models' physical resemblance. The artist tended to generalize the specific details of their facial features, placing the model in a "fabricated" world of his own imagination. In both groups of portraits, Gudiashvili developed so-called soul imprints, idealizing the faces of the people portrayed. Each portrait actively incorporates specific epochal and cultural contexts, with various settings used to characterize the model.

__Zarietta__Gouache_on_paper,_20_x_14,5_cm._1956._ATINATI_Private_Collection_.jpg)

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). Zarietta. Paper, gouache. 20x14,5. 1956. ATINATI Private Collection

In the early 1940s, the image of a beautiful Georgian woman became the central theme of Lado Gudiashvili's work. One of the highlights of his portrait gallery is the simple yet expressive ‘Portrait of Nino Gudiashvili’ (1937). In this portrayal of his wife, the psychological depth conveyed through her introspective gaze and enigmatic smile evokes the finest works of the Italian Renaissance masters. When examining the female faces painted by the artist in the 1940s, the optimism derived from the ennobling power of their beauty is undeniable. Almost all of them are set against a natural landscape or a luxurious interior. The background is in complete harmony with the portrait, adding a romantic touch (‘A Toast with a Golden Horn,’ ‘Poetess’).

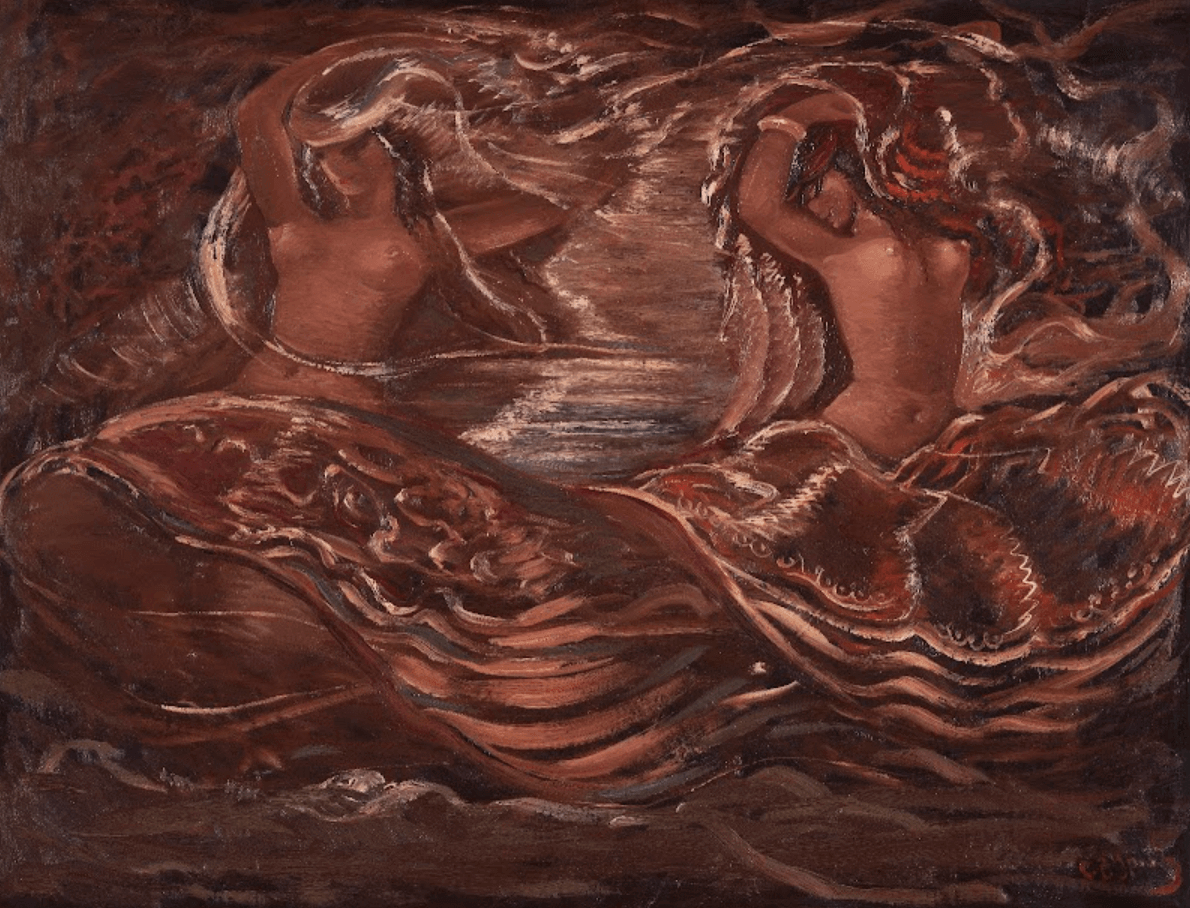

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). Turbulent Dance. Canvas, oil. 61x82,5. 1937

In the 1930s and 1940s, the theme of dance became a prominent part of Lado Gudiashvili's work. For the artist, dance symbolized the orgiastic manifestation of unbridled passions, imbued with excitement and healthy optimism. The swift movement of women's elegant bodies, unusual angles, and hidden romantic sensations subtly engage the viewer. It is well known that the artist felt the rhythm of dance music with every muscle and nerve of his body. Thus, as he followed the rhythm of the dance, his brush painted visual compositions on the canvas with incredible speed: ‘Tourbillion dance,’ ‘Court dancers,’ ‘Dancer OL-OL,’ and others.

The arrival of this new theme in his work led to a considerable change in Gudiashvili’s artistic forms. The bodily contours of his figures became more solid and voluminous. As a result, the picture plane was transformed into a space where the characters could “act,” and the figures began to take on a bas-relief quality (‘Mummy is Kidnapped,’ ‘Wounded Amazon’). The dancing women in Gudiashvili's works "act" against the backdrop of Renaissance-inspired settings, decorated with curtains.

The appearance of the dance theme in Lado Gudiashvili's work was also influenced by the modernist cultural paradigm, which appeared early in the artist's career (dance being one of the key themes of modernist painting). The artist’s experience in stage design also contributed to his approach, as seen in works such as ‘Seraphita's Walk,’ ‘From Armazi Sarcophagus,’ and others. From this cycle, the large-scale canvas ‘Wedding in Armazi’ is noteworthy, featuring approximately 100 characters in the scene.

Gudiashvili painted a number of self-portraits throughout his artistic career, one of which stands out for its use of oil paints to depict the contradictory nature of his character on canvas (‘Autoportrait,’ 1950). This self-portrait reveals the artist's enduring sense of humor, and with it, his attempt to grasp the antagonistic coexistence of two origins in the human subconscious: Apollonian and Dionysian.

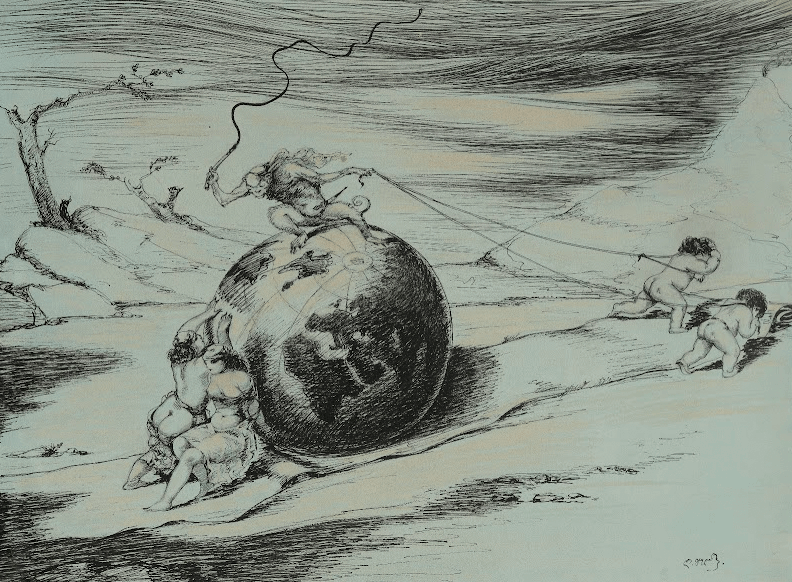

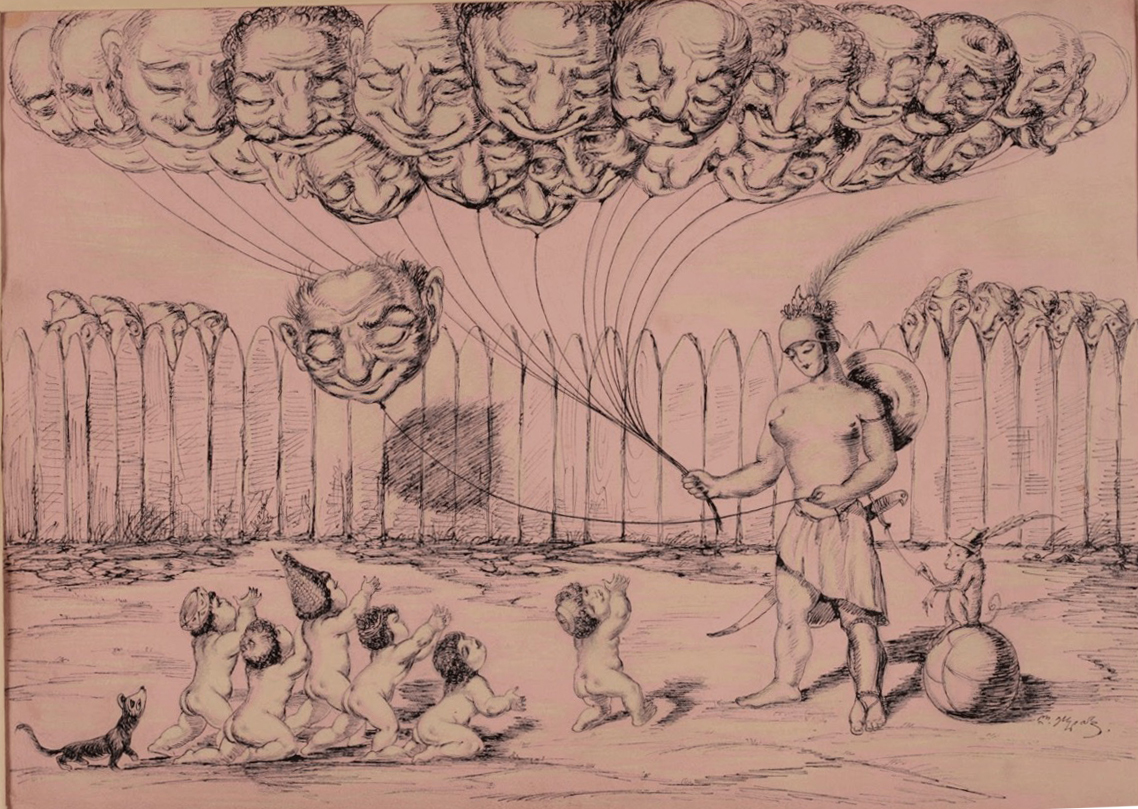

The works created during the Second World War reflect the artist's ambiguous inner nature. The horrors of war and destruction inspired a series of allegorical and symbolic pieces. In 1942, he developed a series of satirical graphic sheets on the theme of World War II. Gudiashvili saw fascism as a universal anti-humanism, born of dictatorial authoritarianism, perpetually fighting against goodness, light, and beauty. In 1942, the artist created a graphic cycle on tinted paper, using ink and pen, to depict the atrocities of not only Hitler, but all wars in general. The artist used graphic language to illustrate scenes depicting the dramatic clash of eternal ideals - goodness, beauty, - against evil, exposing the terrible anti-Semitism of Nazism (‘The Issue of Jews’), the satanic tyranny of warmongers (‘The Power of Satan’), or concern about the cultural heritage doomed to be destroyed by violent war (‘Who knows what we will need it for?’ ‘We do not assume it is a burden’). Gudiashvili's satirical graphical works are notable for their composition and independent, original results.

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). The Generosity of Fascism. Tinted Paper, indian ink. 32x43,5. 1942

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). The Power of Satan. Tinted Paper, indian ink. 32x44. 1942

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). There Are Also Heads Like These. Tinted paper, indian ink. 34x44cm. 1942

In 1947, Georgian Catholicos Kalistrate Tsintsadze offered Lado Gudiashvili the chance to paint the St. George Kashveti Cathedral. The artist eagerly accepted, and began the preparatory work. He had long dreamed of painting the House of God like the unknown masters of the Middle Ages. He drew up the entire painting schedule and started preparing colors using the antiquated encaustic technique. Then he erected the scaffolding and began to work, doing so under the oppressive conditions of Soviet atheism, enduring the greatest physical and psychological stress. However, he was only able to complete his depiction of the Mother of God with Child, the ‘Annunciation’ and ‘Communion’ scenes in the apse of the sanctuary, and the Acheropita icon of Christ in the conch. In 1947, after nine months and nine days of hard work, his efforts were abruptly interrupted by an order from the highest governmental echelons. Following this, the repressive regime’s actions against Gudiashvili worsened, and the artist was confined to his workshop. Gudiashvili had not adhered to the standardized iconographic schemes for Kashveti; instead, he had approached the task in a more secular manner. It might be claimed that the artist imbued the saints' faces with a feeling of modernity, full of internal contradictions. In addition to this, the contemporary figures Catholicos Kalistrate Tsintsadze, Bishop Dimitri Lazrishvili and sculptor Bidzina Avalishvili were depicted as prototypes of the saints.

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). Wall painting at Kashveti Church

Lado Gudiashvili was rarely seen in public for nearly ten years after 1947; but, as later demonstrated, he never ceased his creative pursuits. On May 12, 1958, a retrospective exhibition was held at the National Gallery of Georgia in Tbilisi. The exhibition showcased the artist's numerous explorations, including satirical drawings from 1955 that highlighted moral themes. Through the "language of Aesop," Gudiashvili revealed public and personal vices like arrogance, stupidity, selfishness, megalomania, attention, and censorship (‘The Saga: Faded Wisdom,’ ‘The Megalomania’).

In the 1950s, Lado Gudiashvili remained loyal to the themes that had appeared in his early career, despite the fact that the primary concepts were presented in different artistic forms. These themes, which continued the fairy-tale-fantasy line of the artist's work (‘Fairy Tale,’ ‘Wounded Doe,’ ‘Owners of Fairy Horses’), are reminiscent of the medieval knightly culture expressed in the cult of the beautiful woman, being a pastoral perception of love (‘Spring,’ ‘Kiss on the Hills,’ ‘Waiting for the Betrothed’). The artist, in works like ‘Victim of the Sinful World’, was still in the process of attempting to make sense of the wicked world. Notably, in the oil on canvas ‘Left to Fate,’ a young woman abandoned to fate is depicted on a raft floating down a river, her head near a donkey-headed creature playing the panduri, showcasing the artist's recurring exploration of the contrasts between good and evil, beauty and ugliness, and light and dark.

__Beauty_by_the_Lake_._Pastel,_paper,_76_55_cm,_1973._ATINATI_Private_Collection__Large.jpeg)

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). Beauty by the Lake. Paper, pastel. 76x55. 1973. ATINATI Private Collection

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980).The Unfortunate. Canvas, oil. 80x66. 1930

From the 1960s to the 1970s, Gudiashvili's work underwent noticeable changes. His palette became lighter, more open and translucent as a result of his interest in gouache, pastel, and watercolor techniques. Smaller compositions gradually replaced large canvases, and multi-figure thematic oil works became increasingly rare. The primary element of his work, the line, varied depending on the artist's mood, sometimes flowing and flexible, like an arabesque, at other times more rigid and sharp. He continued to paint portraits and images of beautiful, nude women.

In addition to his painting, Gudiashvili made significant contributions to cinematography, ballet design, and scenography. In collaboration with David Kakabadze, Lado Gudiashvili worked on the set designs for the films ‘Saba’ (1929) and ‘Khabarda’ (1931), both directed by Mikheil Chiaureli. Moreover, together with Valerian Sidamon-Eristavi, Gudiashvili made designs for the movies ‘Doomed’ and ‘Divorce.’ Gudiashvili was the painter for the first Georgian animated film ‘Argonauts (Kolkhida)’ by Vladimir Mujiri. He also directed the artistic part of the film (1935). Gudiashvili returned to animation in 1965, when he was appointed to oversee the artistic aspects of the film ‘How the House was Created,’ directed by Shalva Gedevanishvili, with music by Mary Davitashvili.

Gudiashvili’s ballet ‘Seraphita's Walk,’ which was to feature choreography by Vakhtang Chabukiani and Zurab Kikaleishvili, was never realized. However, 14 sketches of the ballet's costumes, showcasing the artist’s imaginative and refined taste, survived in a private collection (‘In the Atelier of an Artist’). Gudiashvili's fabulous sketches of ballet costumes, with their lightness and modern design, remain relevant today. Like his Parisian friend Pablo Picasso, Gudiashvili continued his artistic search throughout his life. This is evident in the later decades of his career, with a series of works depicting young women, using gouache and resembling mosaic designs (‘The Sunwoman,’ ‘A Fairy from Nabakhtevi,’ etc.). The artist acquired experience working with mosaics when he, together with artist Otar Sulava, participated in the restoration of the Bichvinta mosaics.

Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980). Kiss in the Hills. Canvas, oil. 142x115. 1972

Lado Gudiashvili passed away on July 20, 1980. The grateful Georgian society granted the great artist everlasting rest in the Mtatsminda Pantheon. Lado Gudiashvili achieved immortality through his unparalleled talent.