Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

.jpg)

.jpg)

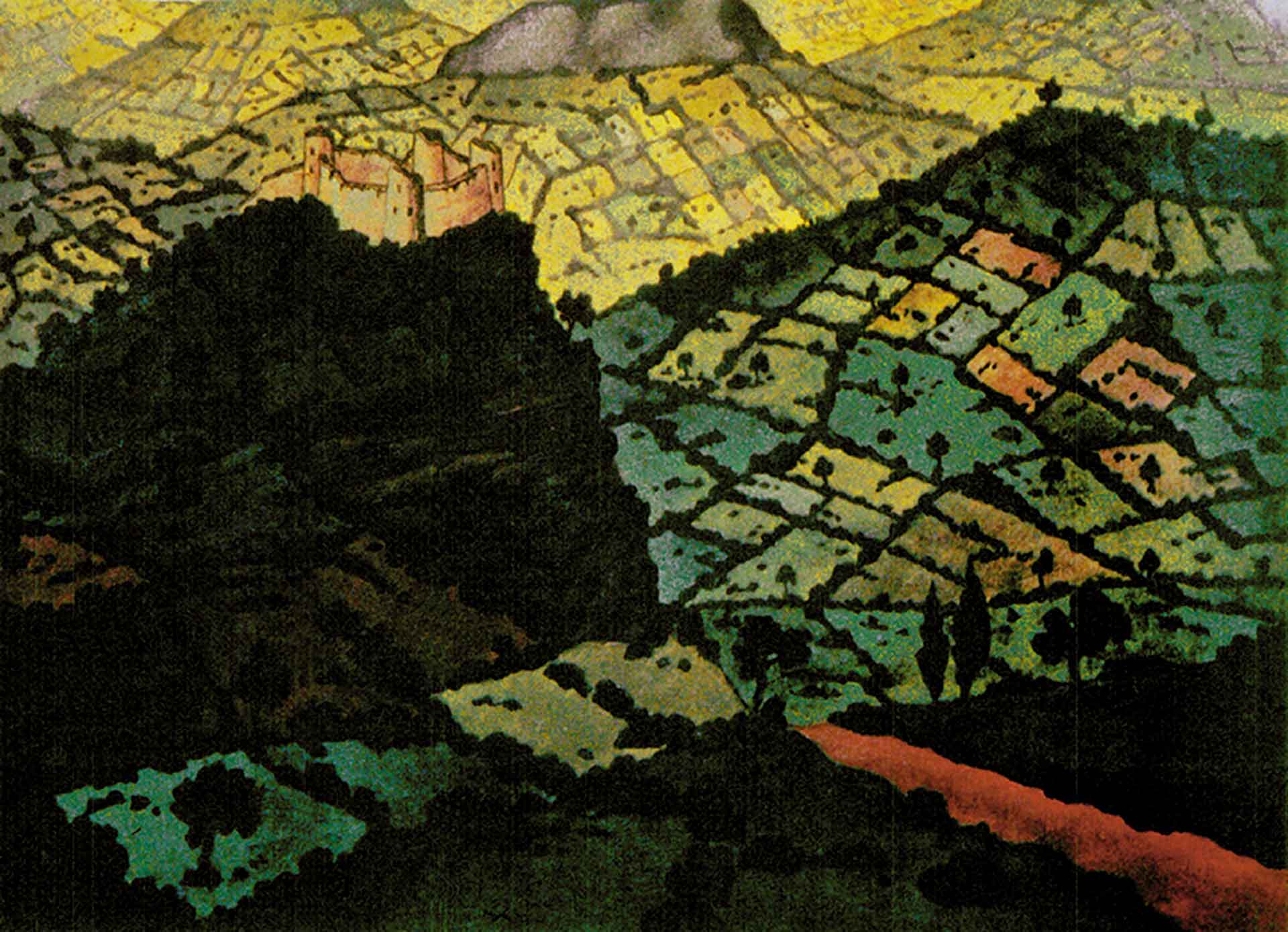

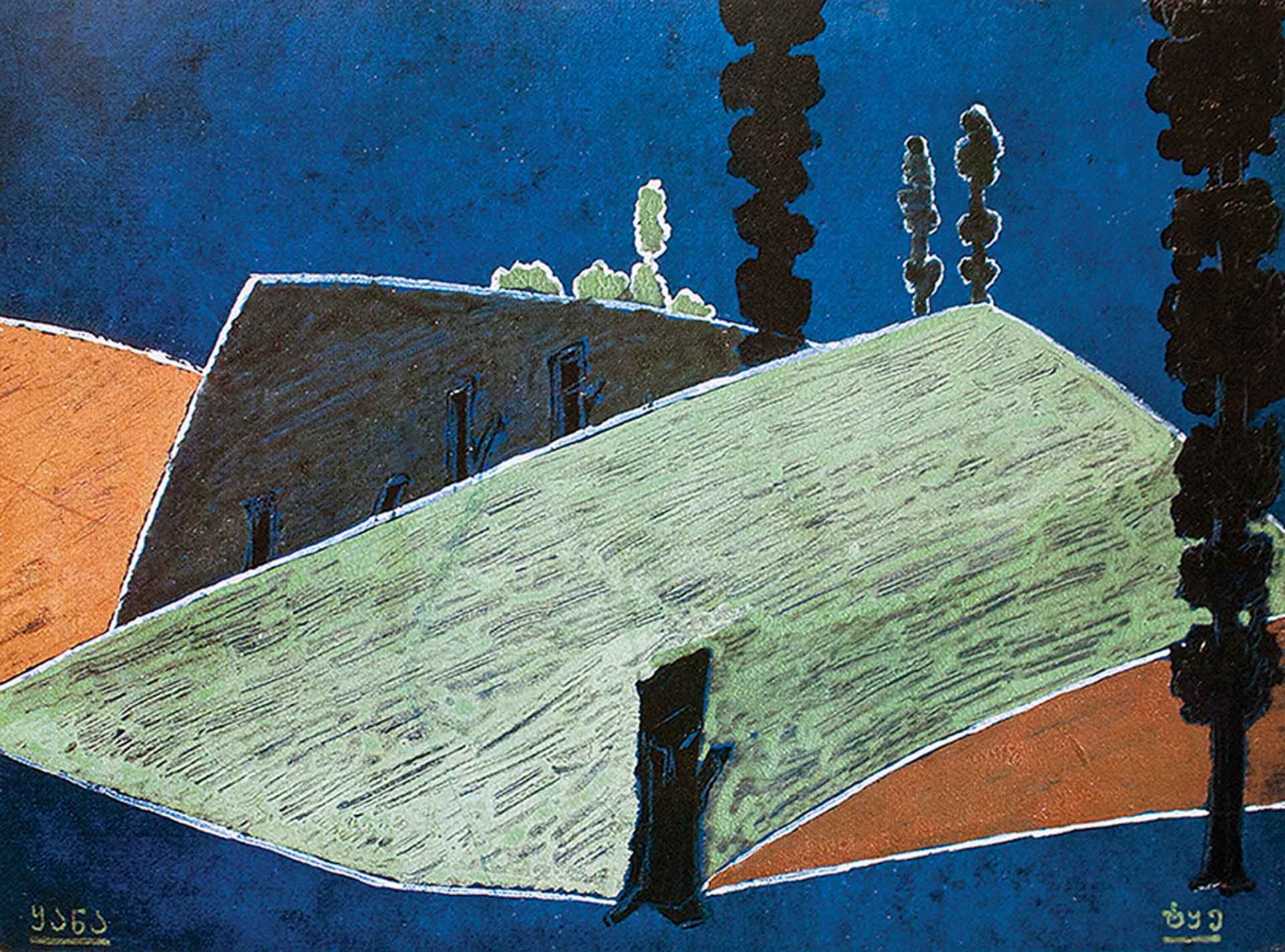

Despite never having boarded a plane, David Kakabadze “flew over” his native land at an altitude of a “bird in flight,” and captured landscapes that ended up becoming symbolic representations of Georgia – truly resembling bird’s-eye views.

D. Kakabadze. Imereti: Red Road. 1918. Oil on canvas, 63 cm ✕ 84 cm. Property of the artist’s family.

D. Kakabadze. Imereti: My Mother. 1918. Oil on canvas. 139 cm ✕157 cm. Georgian National Museum.

Back in 1918, when Georgia adopted the Act of Independence, David Kakabadze created Imereti—My Mother, which is a fusion of two distinct genres: landscape and portrait art. The symbolic composition, featuring his mother and the characteristic atmosphere of his backyard with a panoramic view of Imeretian fields, is an attempt to portray the idea of birthplace, homeland and mother coexisting as one. That same year, David Kakabadze turned 29. He had recently returned from Petrograd (Petersburg), where he had pursued a degree in natural sciences, obtaining a diploma in Biology while simultaneously studying at Lev Dmitriev-Kavkazskiy’s art studio. In 1914, while still enrolled in classes, he created the Cubist Self-Portrait and Funeral in Imereti, both of which demonstrated synthesis of elements from Art Nouveau, Symbolism, Cubism and Futurism. His academic experience in the natural sciences ended up serving as a foundation for his future experiments.

D. Kakabadze. Cubist Self-Portrait. 1914. Oil on canvas. 86 cm x 69 cm. Property of the artist’s family.

Upon his return from Petrograd (Petersburg), where he had been at the very center of matters pertaining to the arts, he came to discover a surprisingly modernist version of Tiflis. The city was then a true melting pot of avant-garde art and literature, with a handful of artistic cafés spread along the central avenue (present-day Rustaveli Avenue, originally known as Golovin Street). David Kakabadze and Lado Gudiashvili were painting murals at Kimerioni, when Titsian Tabidze entered the café to let them know they had won a contest and were soon to be invited to Paris.

In 1919, 30-year-old David Kakabadze arrived in Paris. He had now left the city that was certainly en route to becoming a true hotspot of the global avant-garde movement, and had chosen to immerse himself in the vibrant Parisian cultural scene, which set trends and gave birth to a variety of movements at that time.

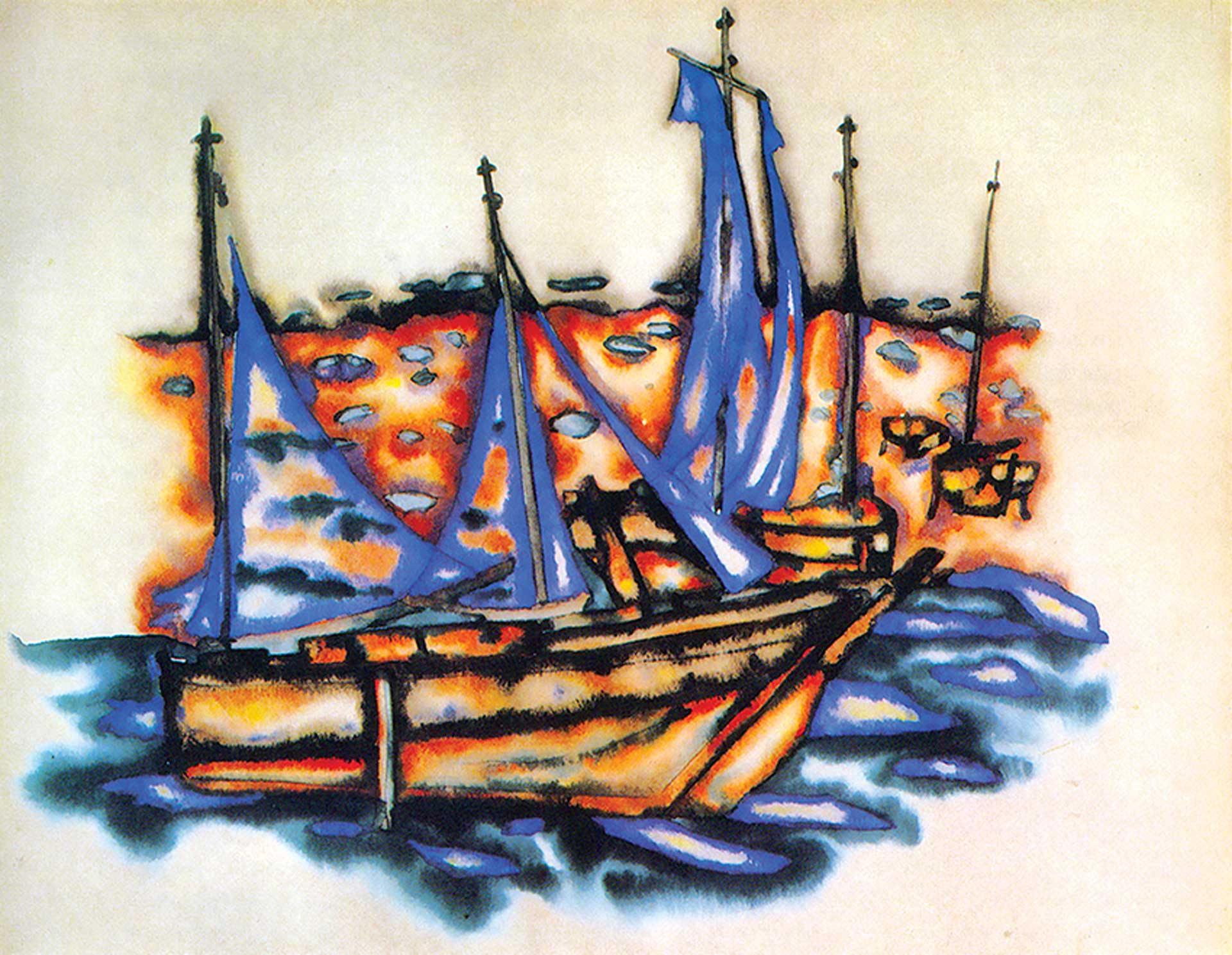

D. Kakabadze. Brittany, 1921. Watercolour on paper. 24 cm x 30 cm. Property of the artist’s family.

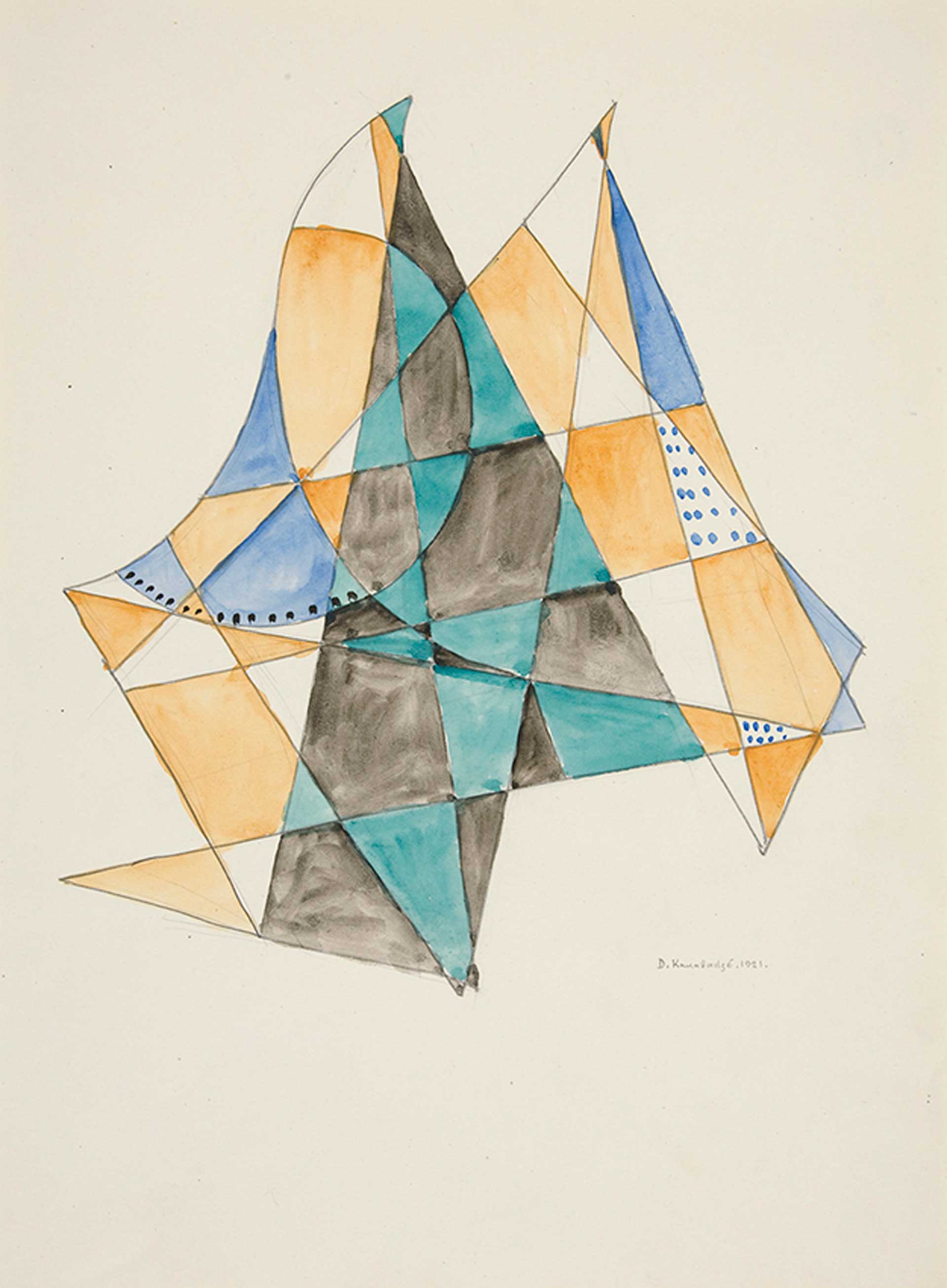

D. Kakabadze. Abstraction Based on Sails. VII. 1921. Watercolor and pencil on paper. 35.4 cm x 25.9 cm. Photo credit: Yale University Art Gallery. Gift of the Collection Société Anonyme. 1941.

D. Kakabadze. Abstraction Based on Flower Forms. III. 1921. Watercolor and pencil on paper. 23.5 cm x 18.2 cm. Photo credit: Yale University Art Gallery. Gift of the Collection Société Anonyme. 1941.

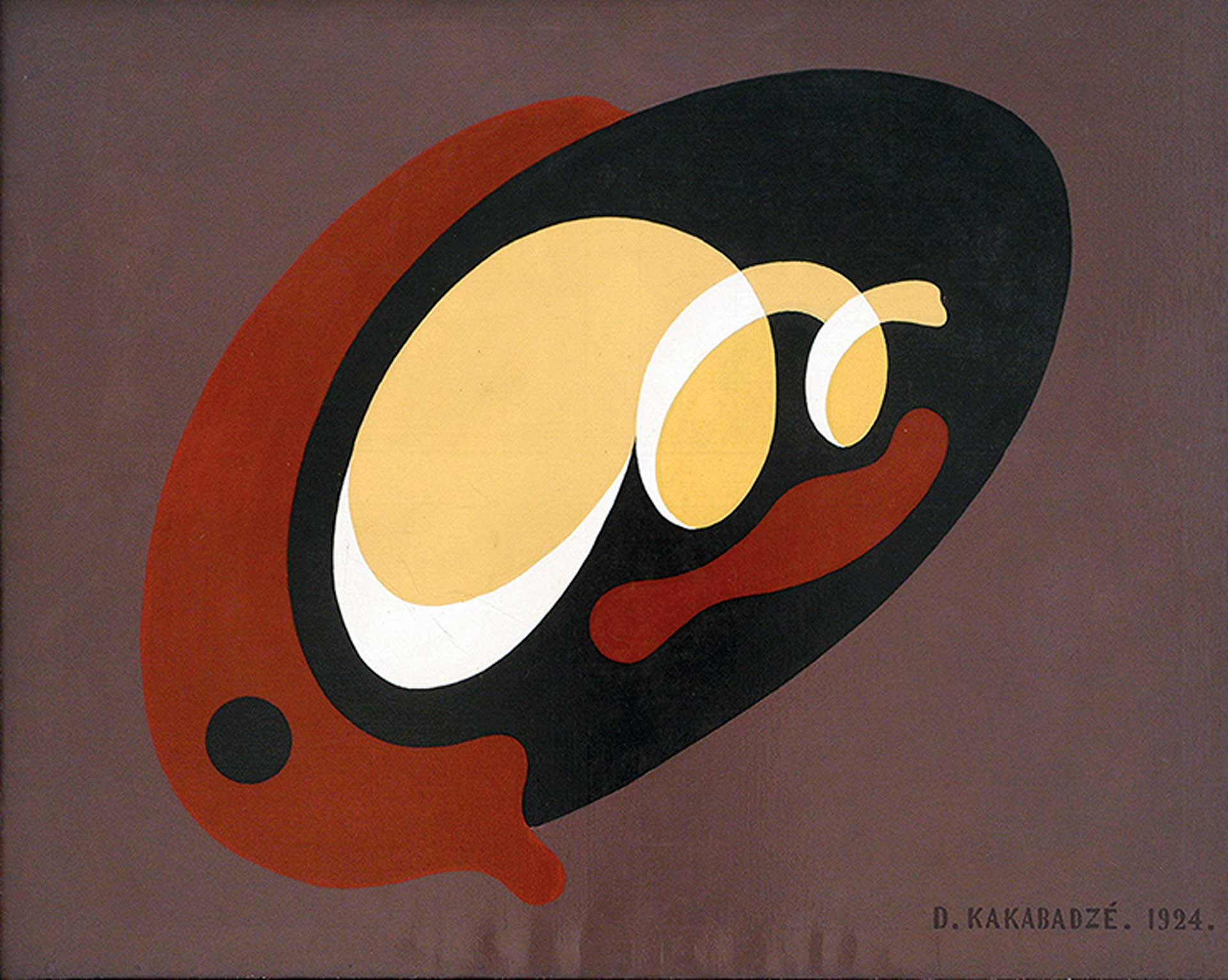

In 1921, the artist visited the province of Brittany, where inspired by the scenery, water, buildings and boats across La Manche (or the English Channel), he created three graphic series in watercolors: the first — inspired by Chinese and Japanese graphics, features considerably more realistic objects; the second — abstract-cubist; and the third — abstract-biomorphic. Later on, these very biomorphic or organic forms ended up serving as the foundation for his larger-sized abstract pieces.

Consequently, David Kakabadze was one of the first artists, along with Joan Miró, Max Ernst and Jean (Hans) Arp, to combine Dada and Surrealism in his abstract paintings. Having come face to face with the issue of depicting space on a two-dimensional plane while experimenting with organic abstract art, Kakabadze became fascinated by the idea of kinetic three-dimensional forms.

D. Kakabadze. Composition. 1923. Oil on canvas. 83 cm x 100 cm. Property of the artist’s family.

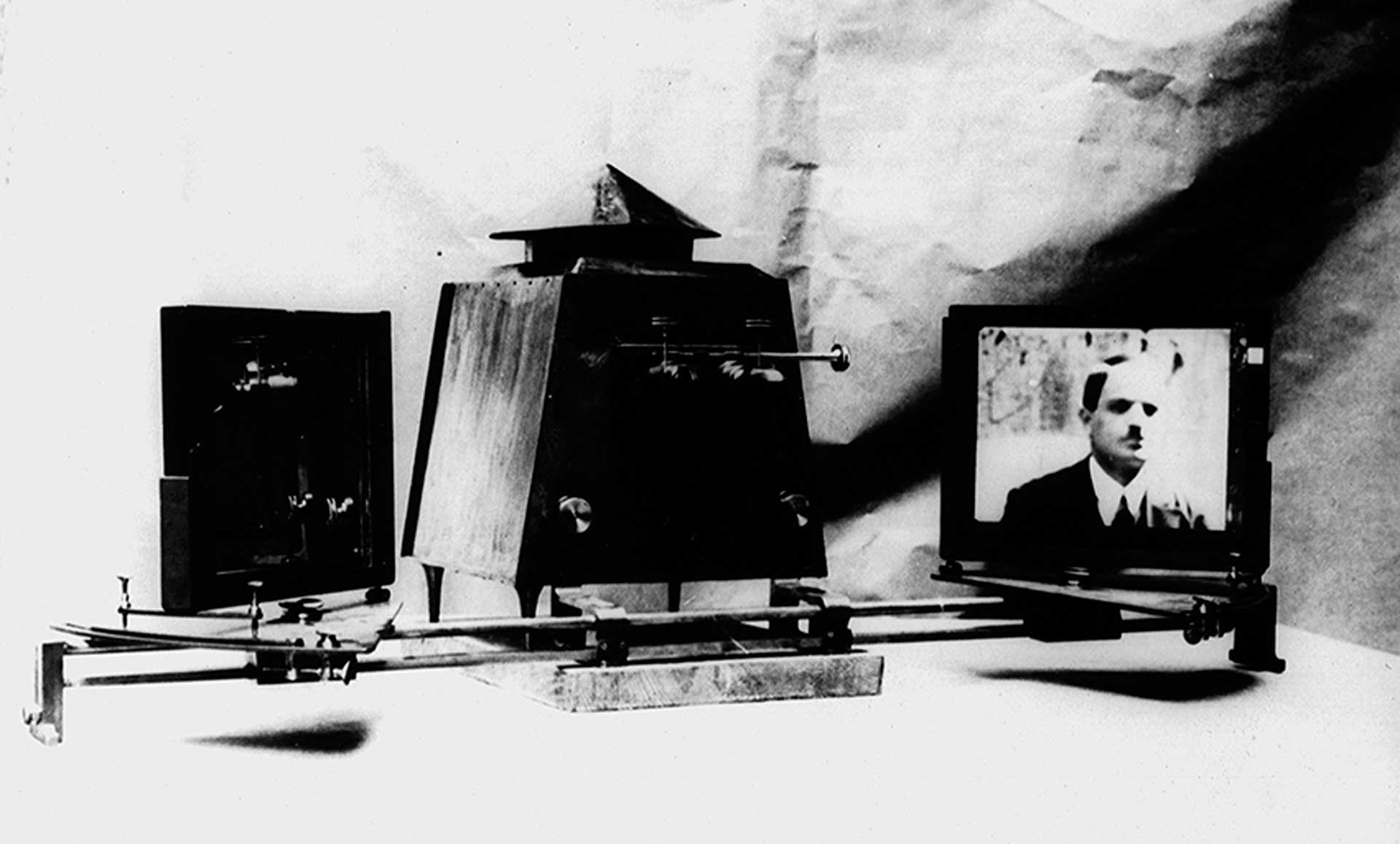

In 1922-23, the artist developed a stereoscopic film projector, for which he obtained numerous international patents. Despite inventing the actual device and successfully obtaining a three-dimensional image, he failed to establish any mass production due to lack of funds. Between 1924 and 1925, he used lenses, mirror glass, springs and a variety of other metal elements to produce a series of original multi-media collages. He even ended up lighting some of the objects from behind with attached bulbs, which proved to be truly astounding. Kakabadze was also one of the first artists to use spray paint for the backgrounds of some of his collages.

D. Kakabadze. Stereoscopic Film Projector Invented by D. Kakabadze. 1924 Photo: Property of the artist’s family.

D. Kakabadze. Constructive-Decorative Composition. 1924. Wood, tempera, metal and optical lenses. 75 cm x 60 cm. Property of the artist’s family.

Between 1921 and 1927, Kakabadze would often be featured in a variety of Parisian newspaper articles and books about contemporary art, which referred to him as a Cubist, a three-dimensional light artist, or the author of electricity-powered collages.

At the Société des Artistes Indépendants in 1926, American artist and philanthropist Katherine Dreier purchased David Kakabadze’s sculpture. She ended up visiting Kakabadze’s studio afterwards, in order to select 18 more works for the International Exhibition of Modern Art at the Brooklyn Museum, which she co-organized with Marcel Duchamp. Here, David Kakabadze had the opportunity to present contemporary works side by side with modern artists and sculptors at the forefront of the Modern Art scene at that time.

D. Kakabadze. Z (The Speared Fish). 1925. Wood, oil, metal and glass. 68.2 cm high (73. 3 cm with wooden base). Photo credit: The Yale University Art Gallery. Bequest of Katherine S. Dreier. 1952.

However, Kakabadze decided to return to his homeland in 1927. Right before leaving Paris, he created a distinct series of abstract art, which resembled both microscopic cell structures and the vault of the sky. Each and every abstract form created by the artist is truly original and unprecedented.

D. Kakabadze. Abstraction. 1927. Oil on cardboard. 46 cm x 60 cm. Property of the artist’s family.

And so he returned to his native city, where the red Bolshevik flag was flying and avant-garde ideas were becoming less and less welcome. Initially, he worked as a scenographer and set designer, taught at the Tbilisi State Academy of the Arts, gave public lectures, and even designed parades. Gradually he returned to landscape art, but was criticized by the Soviet authorities for failing to adapt to the dogmas of Socialist Realism. As a Formalist, he was dismissed from the Academy and denied an income.

D. Kakabadze. Sketch for S. Dadiani’s “Ninoshvili Guria.” 1933. K. Marjanishvili Theatre. Director D. Antadze. Gouache on cardboard. 15.5 cm x 25 cm. Property of the artist’s family.

Frame from the film “Salt for Svanetia.” 1929. Director M. Kalatozishvili. Designer D. Kakabadze.

Consequently, this truly unique and versatile painter, graphic artist, theater and film set designer, scholar and inventor failed to withstand the pressure and became seriously ill. Nevertheless, in the midst of these tough times he managed to author one more invention: the method of producing a volumetric image from a flat image. He even put the idea into practice, and successfully obtained a hologram. In order to align his creative pursuits with the established dogmas, Kakabadze was planning to employ the technique to produce a holographic portrait of Stalin. However, he did not get the chance to bring this avant-garde vision into fruition; repressed and abused from all sides, Kakabadze died from a heart attack in 1952.

D. Kakabadze. Red Mountain. 1944. Oil on canvas. 92 cm x 119 cm. Property of the artist’s family.

At the turn of the twentieth century, David Kakabadze came face to face with the age while standing on an Imeretian hilltop. Through his work he managed to synthesize classic principles with avant-garde ideas, which seldom form an organic ensemble.

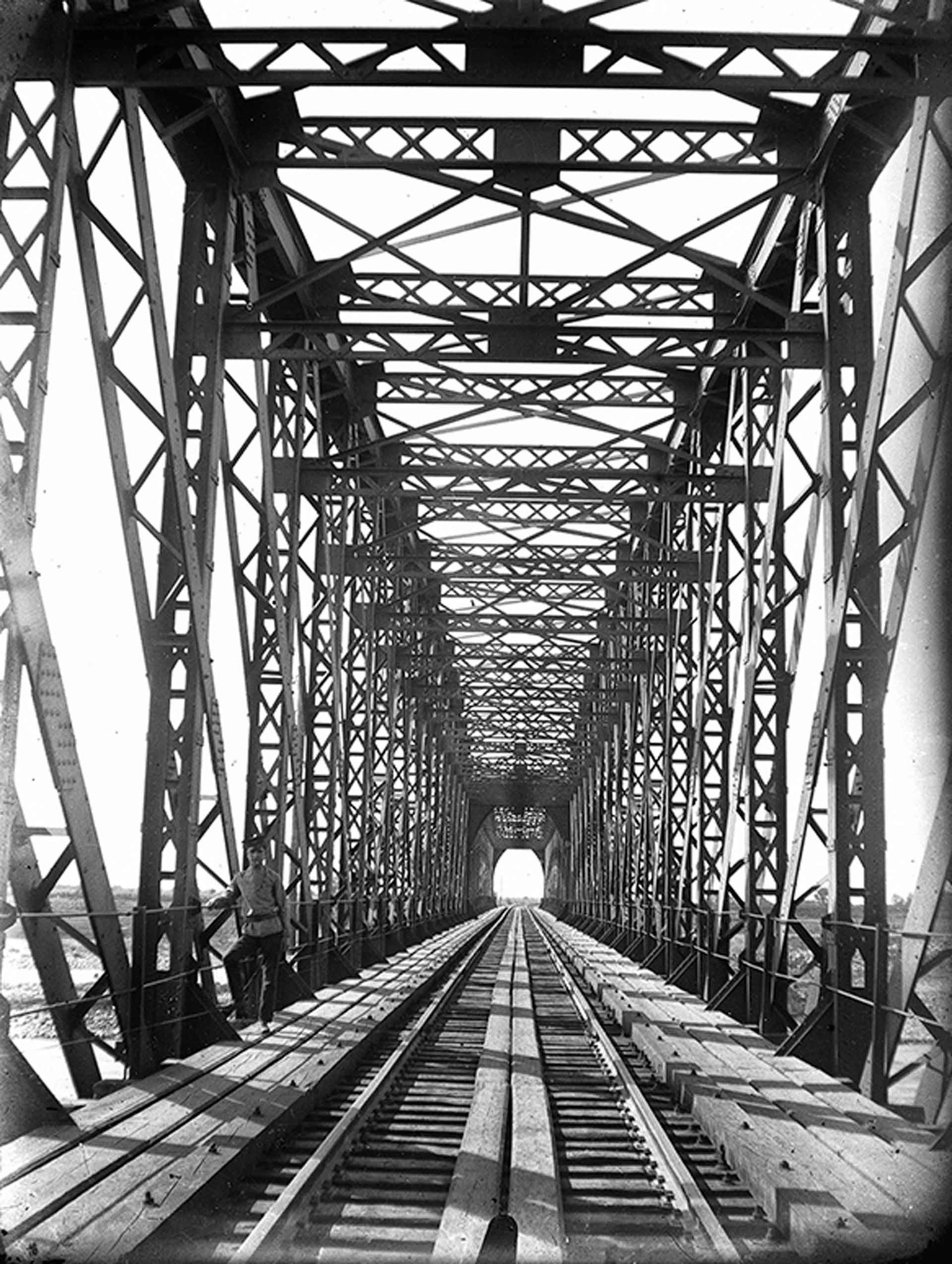

Bridge. Photo by D. Kakabadze. 1910s. Property of the artist’s family.